Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 46

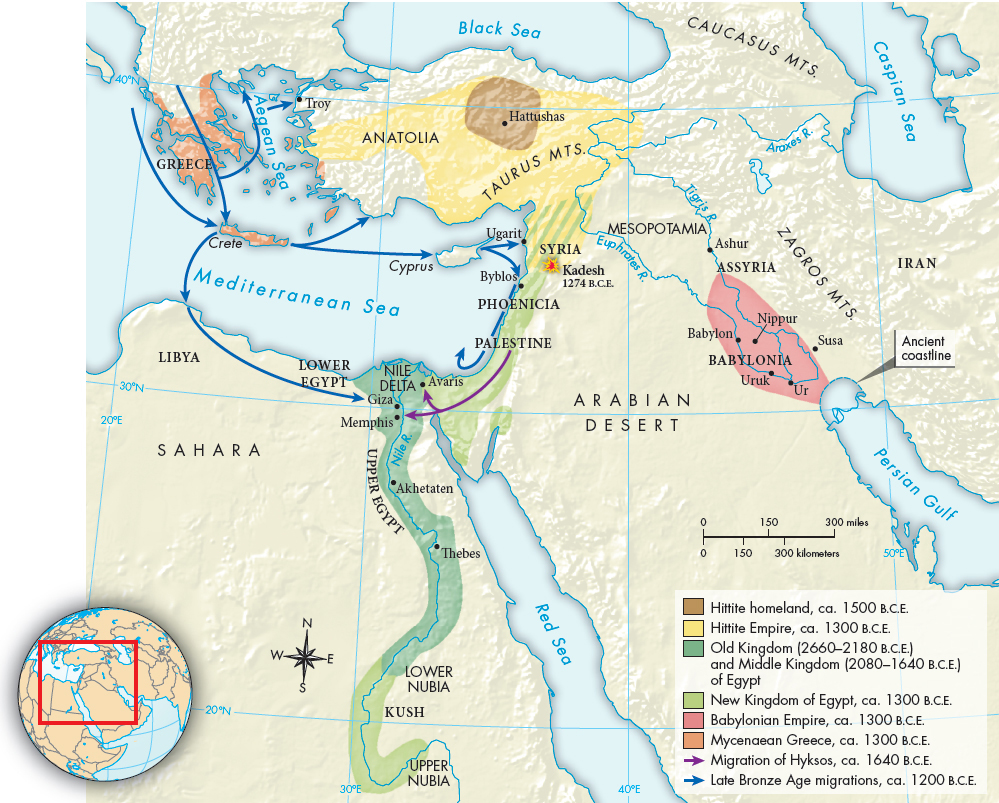

Migrations, Revivals, and Collapse

While Egyptian civilization flourished in the Nile Valley, various groups migrated throughout the Fertile Crescent and then accommodated themselves to local cultures (Map 2.2). Some settled in the Nile Delta, including a group the Egyptians called Hyksos. Although they were later portrayed as a conquering horde, the Hyksos were actually migrants looking for good land, and their entry into the delta, which began around 1800 B.C.E., was probably gradual and generally peaceful. The newcomers began to worship Egyptian deities and modeled their political structures on those of the Egyptians.

ANALYZING THE MAP: At what point was the Egyptian Empire at its largest? The Hittite Empire? What were the other major powers in the eastern Mediterranean at this time?CONNECTIONS: What were the major effects of the migrations of the Hyksos? Of the late Bronze Age migrations? What clues does the map provide as to why the late Bronze Age migrations had a more powerful impact than those of the Hyksos?

The Hyksos brought with them methods of making bronze (see Chapter 1) and casting it into weapons that became standard in Egypt. They thereby brought Egypt fully into the Bronze Age culture of the Mediterranean world. The Hyksos also introduced horse-

In about 1570 B.C.E. a new dynasty of pharaohs arose, pushing the Hyksos out of the delta and conquering territory to the south and northeast. These warrior-

The New Kingdom pharaohs include a number of remarkable figures. Among these was Hatshepsut (haht-

One of the key challenges facing the pharaohs after Akhenaten was the expansion of the kingdom of the Hittites. At about the same time that the Sumerians were establishing city-

The treaty brought peace between the Egyptians and the Hittites for a time, but this stability did not last. Within several decades of the treaty, groups of seafaring peoples whom the Egyptians called “Sea Peoples” raided, migrated, and marauded in the eastern Mediterranean, disrupting trade and in some cases looting and destroying cities. These raids, combined with the expansion of the Assyrians (see “Assyria, the Military Monarchy” in Chapter 2), led to the collapse of the Hittite Empire and the fragmentation of the Egyptian empire. There is evidence of drought, and some scholars have suggested that a major volcanic explosion in Iceland cooled the climate for several years, leading to a series of poor harvests. All of these developments are part of a general “Bronze Age Collapse” in the period around 1200 B.C.E. that historians see as a major turning point.