Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 942

Japan’s Asian Empire

By late 1938, 1.5 million Japanese troops were bogged down in China, holding a great swath of territory but unable to defeat the Nationalists and the Communists (see “Japan Against China” in Chapter 29). In 1939, as war broke out in Europe, the Japanese redoubled their ruthless efforts. Implementing a savage policy of “kill all, burn all, destroy all,” Japanese troops committed shocking atrocities, including the so-

In August 1940 the Japanese announced the formation of a self-

For the moment, however, Japan needed allies. In September 1940 Japan signed a formal alliance (the Axis alliance) with Germany and Italy, and Vichy France granted the Japanese domination over northern French Indochina. The United States, upset with Japan’s occupation of Indochina and fearing embattled Britain would collapse if it lost its Asian colonies, froze scrap iron sales to Japan and applied further economic sanctions in October.

As 1941 opened, Japan’s leaders faced a critical decision. In 1941 the United States was the world’s largest oil producer and supplied over 90 percent of Japan’s oil needs. Japan had only a year and a half’s worth of military and economic oil reserves, which the war in China and the Japanese military and merchant navies were quickly drawing down. On July 26, 1941, President Roosevelt embargoed all oil exports to Japan and froze its assets in the United States. Japan now had to either recall its forces from China or go to war before running out of oil. It chose war.

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. fleet in Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. Japan hoped to cripple its Pacific rival, gain time to build a defensible Asian empire, and eventually win an ill-

The Japanese attack was a limited success. The Japanese sank or crippled every American battleship, but by chance all the American aircraft carriers were at sea and escaped unharmed. Hours later the Japanese destroyed half of the American Far East Air Force stationed at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Americans were humiliated by these unexpected defeats, which soon overwhelmed American isolationism and brought the United States into the war.

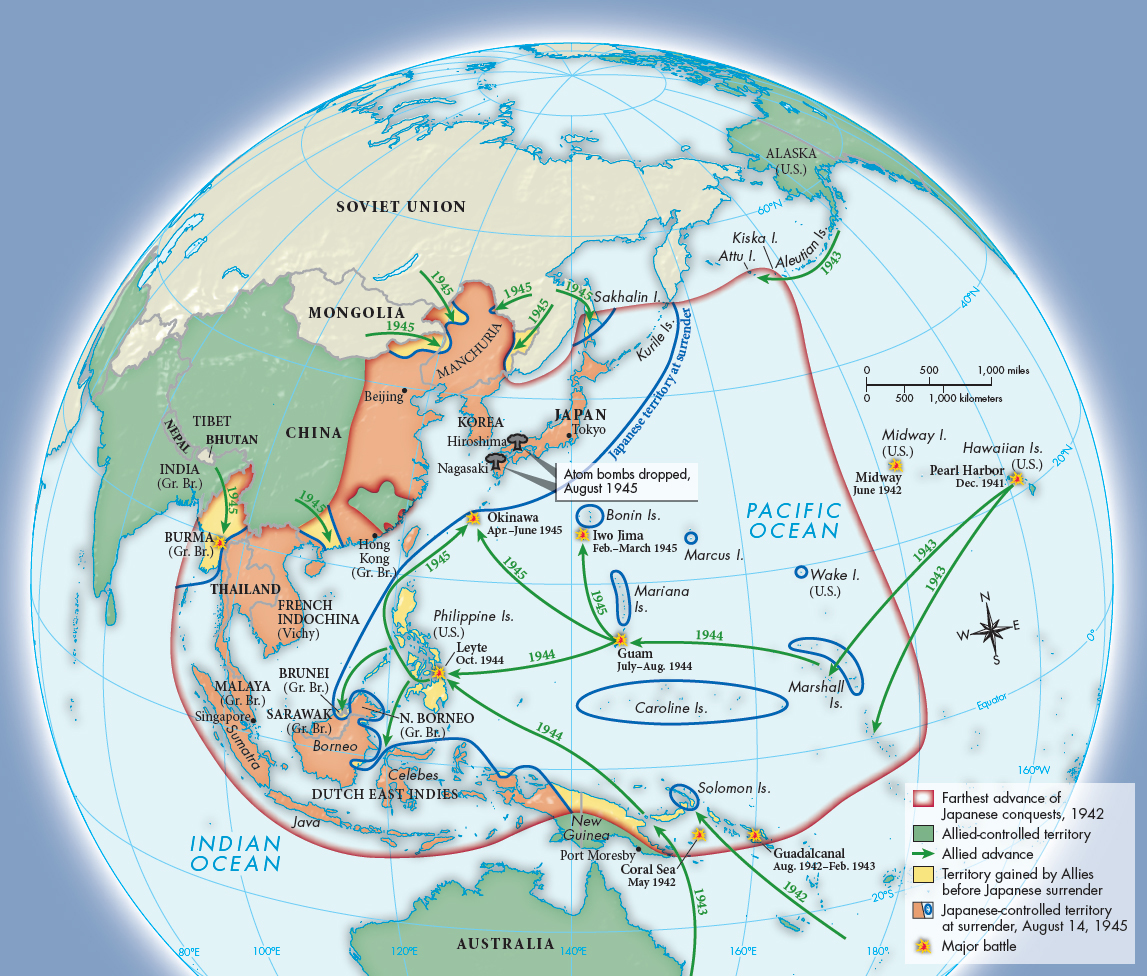

Hitler immediately declared war on the United States. Simultaneously, Japanese armies successfully attacked European and American colonies in Southeast Asia. After American forces surrendered the Philippines in May 1942, Japan held a vast empire in Southeast Asia and the western Pacific (Map 30.3).

ANALYZING THE MAP: Locate the extent of the Japanese empire in 1942, and compare it to the Japanese-

The Japanese claimed they were freeing Asians from Western imperialism, and they called their empire the Greater East Asian Co-

The Japanese often exhibited great cruelty toward prisoners of war and civilians. For example, Dutch, Indonesian, and perhaps as many as two hundred thousand Korean women were forced to provide sex for Japanese soldiers as “comfort women.” Recurring cruel behavior aroused local populations against the invaders.