Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 79

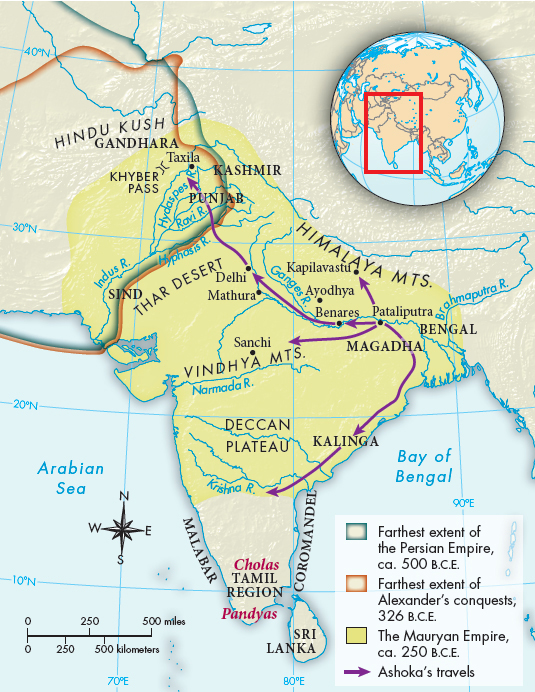

Chandragupta and the Founding of the Mauryan Empire

ANALYZING THE MAP: Where are the major rivers of India? How close are they to mountains?CONNECTIONS: Can you think of any reasons that the Persian Empire and Alexander’s conquests both reached into the same region of northwest India?

The one to benefit most from Alexander’s invasion was Chandragupta, the ruler of a growing state in the Ganges Valley. He took advantage of the crisis caused by Alexander’s invasion to expand his territories, and by 322 B.C.E. he had made himself sole master of north India (Map 3.2). In 304 B.C.E. he defeated the forces of Seleucus.

With stunning effectiveness, Chandragupta applied the lessons learned from Persian rule. He adopted the Persian practice of dividing the area into provinces. Each province was assigned a governor, usually drawn from Chandragupta’s own family. He established a complex bureaucracy to see to the operation of the state and a bureaucratic taxation system that financed public services through taxes on agriculture. He also built a regular army, complete with departments for everything from naval matters to the collection of supplies.

For the first time in Indian history, one man governed most of the subcontinent, exercising control through delegated power. From his capital at Pataliputra in the Ganges Valley, Chandragupta sent agents to the provinces to oversee the workings of government and to keep him informed of conditions in his realm. In designing his bureaucratic system, Chandragupta enjoyed the able assistance of his great minister Kautilya, who wrote a treatise called the Arthashastra on how a king should seize, hold, and manipulate power.

Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus, spent fourteen years in Chandragupta’s court. He left a lively description of life there. He described the city as square and surrounded by wooden walls, twenty-

According to Jain tradition, Chandragupta became a Jain ascetic and died a peaceful death in 298 B.C.E. Although he personally adopted a nonviolent philosophy, he left behind a kingdom with the military might to maintain order and defend India from invasion.