Understanding World Societies:

Printed Page 64

> What does archaeology tell us about the Harappan civilization in India?

Mohenjo-

IIn India, as elsewhere, the possibilities for both agriculture and communication have always been shaped by geography. Monsoon rains sweep northward from the Indian Ocean each summer. The lower reaches of the Himalaya Mountains in the northeast are covered by dense forests. Immediately to the south are the fertile valleys of the Indus and Ganges Rivers. These lowland plains, which stretch all the way across the subcontinent, were tamed for agriculture over time, and India’s great empires were centered there. To their west are the deserts of Rajasthan and southeastern Pakistan, historically important in part because their flat terrain enabled invaders to sweep into India from the northwest. South of the great river valleys rise the Vindhya Mountains and the dry, hilly Deccan Plateau. Only along the western coast of this part of India do the hills give way to narrow plains where crop agriculture flourished (Map 3.1). India’s long coastlines and predictable winds fostered maritime trade with other countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

Agriculture was well established in India by about 7000 B.C.E. Wheat and barley were the early crops, probably having spread in their domesticated form from what is today the Middle East. Farmers also domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats and learned to make pottery.

India’s first civilization is known today as the Indus Valley or the Harappan (huh-

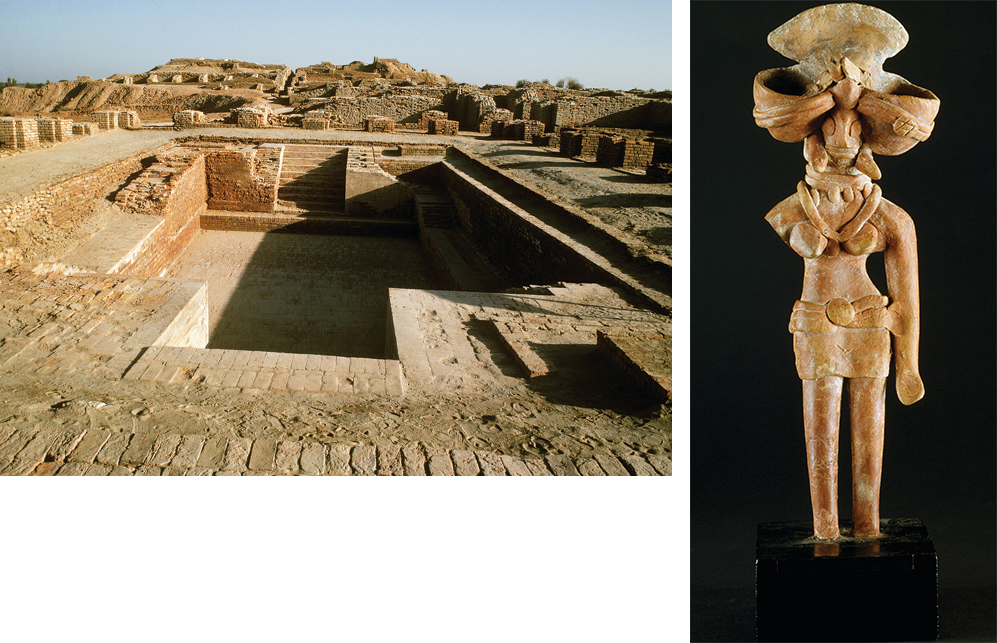

The Harappan civilization extended over nearly five hundred thousand square miles in the Indus Valley, making it more than twice as large as ancient Egypt or Sumer. Yet Harappan civilization was marked by striking uniformity. Throughout the region, for instance, even in small villages, bricks were made to the same standard proportion (4:2:1). Figurines of pregnant women have been found throughout the area, suggesting common religious ideas and practices.

Like Mesopotamian cities, Harappan cities were centers for crafts and trade and were surrounded by extensive farmland. The Harappans were the earliest known manufacturers of cotton cloth. Trade was extensive. As early as the reign of Sargon of Akkad in the third millennium B.C.E. (see “Empires in Mesopotamia” in Chapter 2), trade between India and Mesopotamia carried goods and ideas between the two cultures, probably by way of the Persian Gulf.

The cities of Mohenjo-

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the elaborate planning of these cities was their complex system of drainage. Each house had a bathroom with a drain connected to brick-

Both Mohenjo-

The prosperity of the Indus civilization depended on constant and intensive cultivation of the rich river valley. Although rainfall seems to have been greater then than in recent times, the Indus, like the Nile, flowed through a relatively dry region made fertile by annual floods and irrigation. And as in Egypt, agriculture was aided by a long, hot growing season and near-

Because no one has yet deciphered the written language of the Harappan people, their political, intellectual, and religious life is largely unknown. There clearly was a political structure with the authority to organize city planning and facilitate trade, but we do not even know whether there were hereditary kings.

Soon after 2000 B.C.E., the Harappan civilization mysteriously declined. The decline cannot be attributed to the arrival of powerful invaders, as was once thought. Rather it was internally generated. Environmental theories include an earthquake that led to a shift in the course of the river, or a severe drought. Some scholars speculate that long-

>QUICK REVIEW

What do the archeological remains of the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-