Chapter 1. 1: Introduction and Research Methods

Chapter Introduction

MYTH OR SCIENCE?

Is it true …

That the field of psychology primarily focuses on treating people with psychological problems and disorders?

That Sigmund Freud was the first psychologist?

That when two behaviors are “linked,” “related,” or tend to occur together, it’s safe to assume that one behavior caused the other?

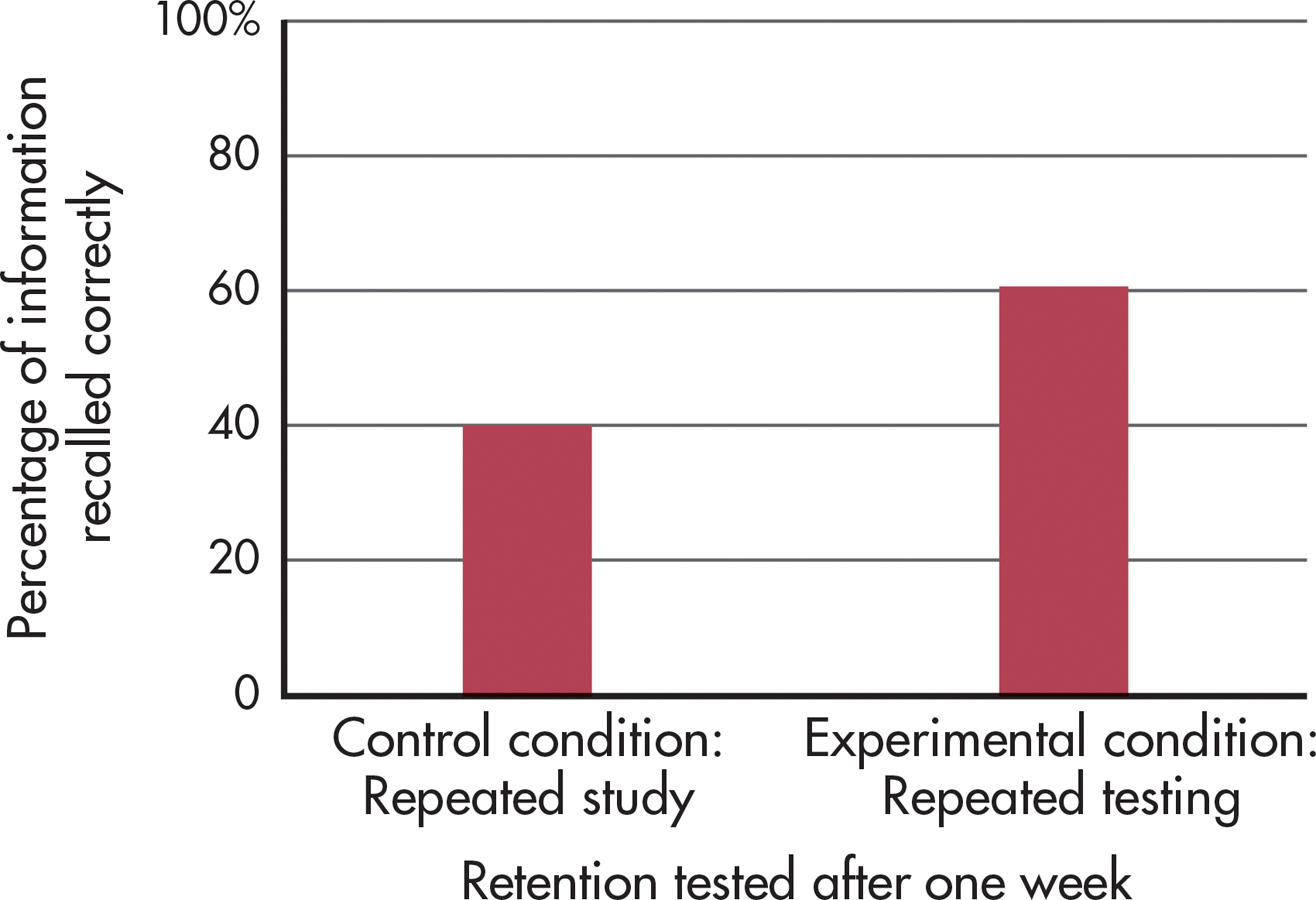

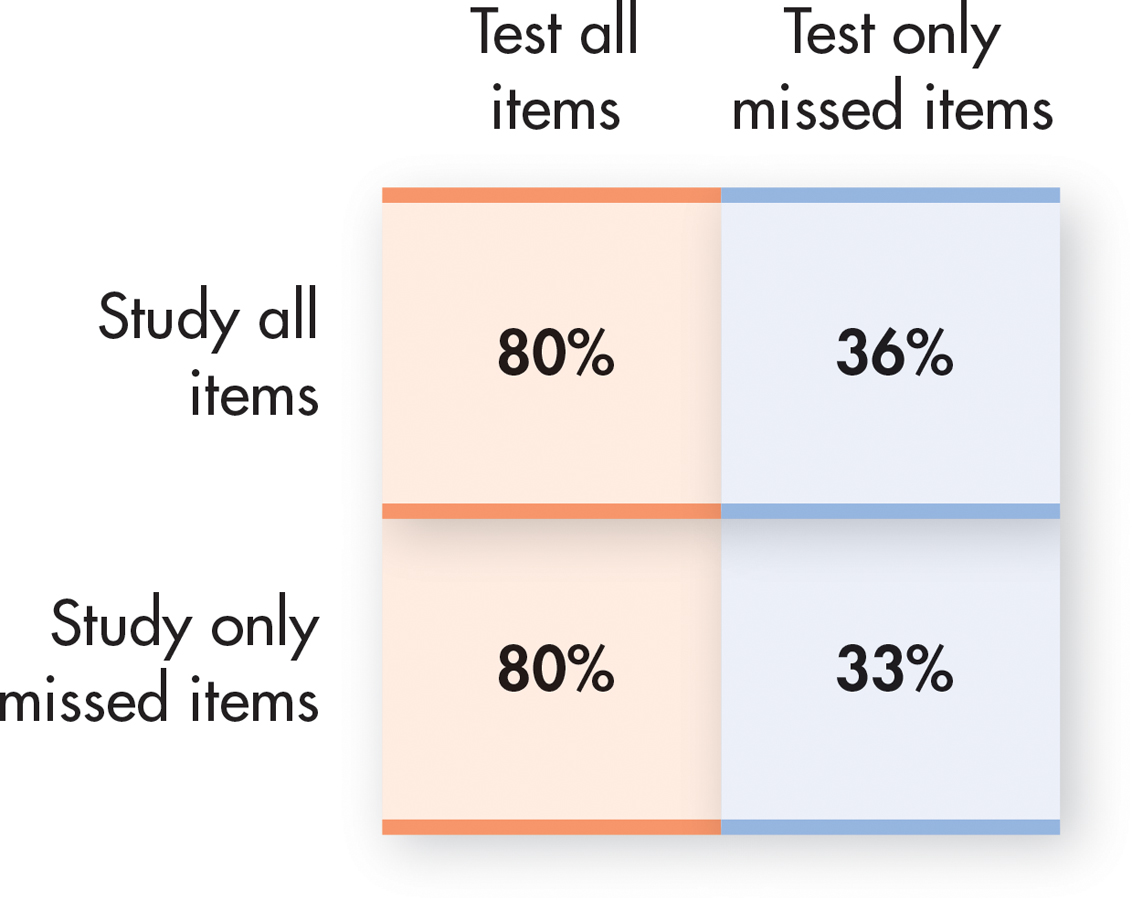

That reading something over and over again is not the most effective way to prepare for a test?

That psychologists can trick you into taking part in a study?

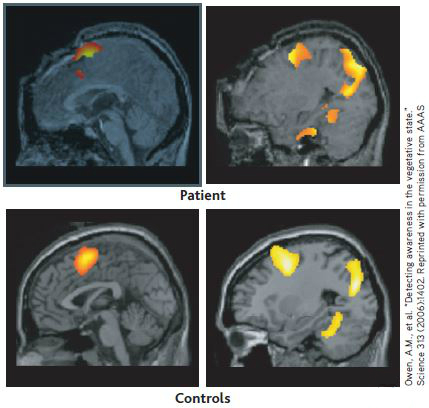

That brain scans can pinpoint the exact, single part of the brain that causes a complex behavior?

1

Introduction and Research Methods

Steve Cukrov/Shutterstock

The First Exam

PROLOGUE

IN THIS CHAPTER:

INTRODUCTION: What Is Psychology?

Contemporary Psychology

The Scientific Method

Descriptive Research

Experimental Research

Ethics in Psychological Research

PSYCH FOR YOUR LIFE: Successful Study Techniques

YOU DON’T NEED TO BE A PSYCHOLOGIST to notice that the classroom atmosphere can be a little tense the day after the first exam. As we handed back the test results, several faces fell. Many of the students were freshmen and not yet accustomed to the self-paced learning required in a college course. But there were also several older adults, including two military vets, one recently returned from Afghanistan.

“So let’s go over these test questions,” your author Sandy began. “I noticed a lot of you had trouble with the difference between independent and dependent variables. Maybe we should talk about that again before we go on to Chapter 2.”

Jacob frowned. “I can’t understand why I did so badly,” he said. “I mean, I read the chapter! Look.” He held up his textbook. The pages were heavily underlined and covered with highlight colors—yellow, blue, and green.

It isn’t unusual for students to have trouble with their first real exam in college. Knowing that, we usually take some time to talk about study skills after exams are returned. “How did you prepare for the exam?” your author Susan asked the class.

“I made flashcards,” Latisha said. “But it didn’t seem to help that much. I only got a B-, and I thought I really knew this stuff.”

“Flashcards can be a great technique,” Sandy said, “if you use them correctly.”

Latisha looked puzzled. “What do you mean? I used them the way everybody uses flashcards. I tested myself and if I knew the answer, I set the card aside. I kept running through the ones I missed until they were all gone and I knew them all.”

“Well, believe it or not,” Sandy said, “psychologists have done a lot of research on learning new material, and it turns out that that’s not the most effective way to use flashcards.”

“What is, then?” Latisha asked.

“Stay tuned,” Sandy said with a smile. “We’re going to talk about it in today’s class.”

Jenna broke in. “I always freeze on tests. They stress me out so bad my mind goes blank.”

“I do too,” Tyler piped up. “So my girlfriend gave me this bracelet to wear for exams. She swears by hers. Do you think it helps?”

“What is that?” Sandy said. Tyler handed the heavy metal bracelet to Sandy. “What’s it supposed to do?”

“It’s made of some kind of special metal—maybe titanium?” Tyler said. “It’s magnetic. Oh, and the Web site said it generated a negative ion field, or maybe it neutralizes positive ions. It didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me. But my girlfriend said that a lot of famous baseball players and golfers wear one. It’s supposed to help with pain but it’s also supposed to help you concentrate and give you a better memory. I figured it couldn’t hurt, so why not try it?”

“I’m not aware of any research on using magnets for concentration or memory,” Sandy said carefully. “But we can certainly look it up and let you know what we find out.”

Later in the chapter, we’ll share what we found out about magnetic jewelry—and more important, what psychologists have discovered about the most effective ways to study. You’ll also see how psychological research can help you critically evaluate new ideas and claims that you encounter outside the classroom.

As you’ll see throughout this book, psychology has a lot to say about many of the questions that are of interest to college students. In this introductory chapter, we’ll explore the scope of contemporary psychology as well as psychology’s historical origins. The common theme connecting psychology’s varied topics is its reliance on a solid foundation of scientific evidence. By the end of the chapter, you’ll have a better appreciation of the scientific methods that psychologists use to answer questions, big and small, about behavior and mental processes.

Welcome to psychology!

| Country | GDP | Assets | Country | GDP | Assets | Country | GDP | Assets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 43.8 | 199 | Switzerland | 67.4 | 358 | Germany | 44.7 | 145 |

| Australia | 47.4 | 166 | Netherlands | 52.0 | 242 | Belgium | 47.1 | 167 |

| United States | 47.9 | 191 | Japan | 38.6 | 176 | Sweden | 52.8 | 169 |

| Singapore | 40.0 | 168 | Denmark | 62.6 | 224 | Spain | 35.3 | 152 |

| Canada | 45.4 | 170 | France | 46.0 | 149 | Ireland | 61.8 | 214 |

| Year (x) | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 2008 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stores (y) | 420 | 463 | 506 | 554 | 1682 | 1916 |

1.1 INTRODUCTION: What Is Psychology?

KEY THEME

Today, psychology is defined as the science of behavior and mental processes, a definition that reflects psychology’s origins and history.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is the scope of contemporary psychology?

What roles did Wundt and James play in establishing psychology?

What were the early schools of thought and approaches in psychology, and how did their views differ?

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that the field of psychology primarily focuses on treating people with psychological problems and disorders?

Psychology is formally defined as the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. But this definition is deceptively simple. As you’ll see in this chapter, the scope of contemporary psychology is very broad—ranging from the behavior of a single brain cell to the behavior of a crowd of people or even entire cultures.

psychology

The scientific study of behavior and mental processes.

Many people think that psychologists are primarily—or even exclusively—interested in studying and treating psychological disorders and problems. But as this chapter will also show, psychologists are just as interested in “normal,” everyday behavior and mental processes—such as learning and memory, emotion and thought, relationships and loneliness. And, psychologists seek ways to use the knowledge that they discover through scientific research to optimize human performance and potential in many different fields, from classrooms to offices to the military.

The four basic goals of psychology are to describe, predict, explain, and control or influence behavior and mental processes. To illustrate how these goals guide psychological research, think about our classroom discussion. Most people, like Jenna, have an intuitive understanding of what the word “stress” refers to. Psychologists, however, seek to go beyond intuitive or “common sense” understandings of human experience.

Here’s how psychology’s goals might help guide research on stress:

Describe: Trying to objectively describe the experience of stress, Dr. Garcia studies the sequence of emotional responses that occur during stressful experiences.

Predict: Dr. Kiecolt investigates responses to different kinds of challenging events, hoping to be able to predict the kinds of events that are most likely to evoke a stress response.

Explain: Seeking to explain why some people are more vulnerable to the effects of stress than others, Dr. Lazarus studies the different ways that people respond to natural disasters.

Control or Influence: After studying the effectiveness of different coping strategies, Dr. Folkman helps people use those coping strategies to better control their reactions to stressful events.

How did psychology evolve into today’s diverse and rich science? We begin this introductory chapter by stepping backward in time to describe the early origins of psychology and its historical development. As you become familiar with how psychology began and developed, you’ll have a better appreciation for how it has come to encompass such diverse subjects. Indeed, the early history of psychology is the history of a field struggling to define itself as a separate and unique scientific discipline. The early psychologists debated such fundamental issues as:

What is the proper subject matter of psychology?

What methods should be used to investigate psychological issues?

Should psychological findings be used to change or enhance human behavior?

These debates helped set the tone of the new science, define its scope, and set its limits. Over the past century, the shifting focus of these debates has influenced the topics studied and the research methods used.

| Lot | x = square footage

(100s of sq. ft.) |

y = sales price

($1000s) |

|---|---|---|

| Harding St. | 75 | 155 |

| Newton Ave. | 125 | 210 |

| Stacy Ct. | 125 | 290 |

| Eastern Ave. | 175 | 360 |

| Second St. | 175 | 250 |

| Sunnybrook Rd. | 225 | 450 |

| Ahlstrand Rd. | 225 | 530 |

| Eastern Ave. | 275 | 635 |

Unnumbered table below

| To do | Check out | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Exercises 9-12 | Example 1 | Predictor variables and response variables |

| Exercises 13a-20a | Example 2 | Constructing a scatterplot |

| Exercises 13b-20b and 21-26 |

Example 3 | Describing the relationship between x and y |

| Exercises 13c-20c and 31-34 |

Example 4 | Calculating the correlation coefficient r |

| Exercises 13d-20d and 27-30 |

Example 5 | Interpreting the correlation coefficient r |

Psychology’s Origins: THE INFLUENCE OF PHILOSOPHY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The earliest origins of psychology can be traced back several centuries to the writings of the great philosophers. More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote extensively about topics like sleep, dreams, the senses, and memory. Many of Aristotle’s ideas remained influential until the beginnings of modern science in the seventeenth century (Kheriaty, 2007).

At that time, the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–

Philosophers also laid the groundwork for another issue that would become central to psychology, the nature–

Such philosophical discussions influenced the topics that would be considered in psychology. But the early philosophers could advance the understanding of human behavior only to a certain point. Their methods were limited to intuition, observation, and logic.

The eventual emergence of psychology as a science hinged on advances in other sciences, particularly physiology. Physiology is a branch of biology that studies the functions and parts of living organisms, including humans. In the 1600s, physiologists were becoming interested in the human brain and its relation to behavior. By the early 1700s, it was discovered that damage to one side of the brain produced a loss of function in the opposite side of the body. By the early 1800s, the idea that different brain areas were related to different behavioral functions was being vigorously debated. Collectively, the early scientific discoveries made by physiologists were establishing the foundation for an idea that was to prove critical to the emergence of psychology—namely, that scientific methods could be applied to answering questions about behavior and mental processes.

Wilhelm Wundt: THE FOUNDER OF PSYCHOLOGY

By the second half of the 1800s, the stage had been set for the emergence of psychology as a distinct scientific discipline. The leading proponent of this idea was a German physiologist named Wilhelm Wundt (Gentile & Miller, 2009). Wundt used scientific methods to study fundamental psychological processes, such as mental reaction times in response to visual or auditory stimuli. For example, Wundt tried to measure precisely how long it took a person to consciously detect the sight and sound of a bell being struck.

A major turning point in psychology occurred in 1874, when Wundt outlined the connections between physiology and psychology in his landmark text, Principles of Physiological Psychology (Diamond, 2001). He also promoted his belief that psychology should be established as a separate scientific discipline that would use experimental methods to study mental processes. A few years later, in 1879, Wundt realized that goal when he opened the first psychology research laboratory at the University of Leipzig. Many regard this event as marking the formal beginning of psychology as an experimental science (Kohls & Benedikter, 2010).

Wundt defined psychology as the study of consciousness and emphasized the use of experimental methods to study and measure consciousness. Until he died in 1920, Wundt exerted a strong influence on the development of psychology as a science (Wong, 2009). Two hundred students from around the world traveled to Leipzig to earn doctorates in experimental psychology under Wundt’s direction. Over the years, some 17,000 students attended Wundt’s afternoon lectures on general psychology, which often included demonstrations of devices he had developed to measure mental processes (Blumenthal, 1998).

Edward B. Titchener: STRUCTURALISM

One of Wundt’s most devoted students was a young Englishman named Edward B. Titchener. After earning his doctorate in Wundt’s laboratory, Titchener began teaching at Cornell University in New York. There he established a psychology laboratory that ultimately spanned 26 rooms.

Titchener shared many of Wundt’s ideas about the nature of psychology. Eventually, however, Titchener developed his own approach, which he called structuralism. Structuralism became the first major school of thought in psychology. Structuralism held that even our most complex conscious experiences could be broken down into elemental structures, or component parts, of sensations and feelings. To identify these structures of conscious thought, Titchener trained subjects in a procedure called introspection. The subjects would view a simple stimulus, such as a book, and then try to reconstruct their sensations and feelings immediately after viewing it. (In psychology, a stimulus is anything perceptible to the senses, such as a sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste.) They might first report on the colors they saw, then the smells, and so on, in the attempt to create a total description of their conscious experience (Titchener, 1896).

structuralism

Early school of psychology that emphasized studying the most basic components, or structures, of conscious experiences.

In addition to being distinguished as the first school of thought in early psychology, Titchener’s structuralism holds the dubious distinction of being the first school to disappear. With Titchener’s death in 1927, structuralism as an influential school of thought in psychology essentially ended. But even before Titchener’s death, structuralism was often criticized for relying too heavily on the method of introspection.

As noted by Wundt and other scientists, introspection had significant limitations. First, introspection was an unreliable method of investigation. Different subjects often provided very different introspective reports about the same stimulus. Even subjects well trained in introspection varied in their responses to the same stimulus from trial to trial.

Second, introspection could not be used to study children or animals. Third, complex topics, such as learning, development, mental disorders, and personality, could not be investigated using introspection. In the end, the methods and goals of structuralism were simply too limited to accommodate the rapidly expanding interests of the field of psychology.

William James: FUNCTIONALISM

By the time Titchener arrived at Cornell University, psychology was already well established in the United States. The main proponent of American psychology was one of Harvard’s most outstanding teachers—William James. James had become intrigued by the emerging science of psychology after reading one of Wundt’s articles. But there were other influences on the development of James’s thinking.

Like many other scientists and philosophers of his generation, James was fascinated by the idea that different species had evolved over time (Menand, 2001). Many nineteenth-century scientists in England, France, and the United States were evolutionists—that is, they believed that species had not been created once and for all but had changed over time (Caton, 2007).

In the 1850s, British philosopher Herbert Spencer had published several works arguing that modern species, including humans, were the result of gradual evolutionary change. In 1859, Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking work, On the Origin of Species, was published. James and his fellow thinkers actively debated the notion of evolution, which came to have a profound influence on James’s ideas (Richardson, 2006). Like Darwin, James stressed the importance of adaptation to environmental challenges.

In the early 1870s, James began teaching a physiology and anatomy class at Harvard University. An intense, enthusiastic teacher, James was prone to changing the subject matter of his classes as his own interests changed (B. Ross, 1991). By the late 1870s, James was teaching classes devoted exclusively to the topic of psychology.

At about the same time, James began writing a comprehensive textbook of psychology, a task that would take him more than a decade. James’s Principles of Psychology was finally published in 1890. Despite its length of more than 1,400 pages, Principles of Psychology quickly became the leading psychology textbook. In it, James discussed such diverse topics as brain function, habit, memory, sensation, perception, and emotion. James’s views had an enormous impact on the development of psychology in the United States.

James’s ideas became the basis for a new school of psychology, called functionalism. Functionalism stressed the importance of how behavior functions to allow people and animals to adapt to their environments. Unlike structuralists, functionalists did not limit their methods to introspection. They expanded the scope of psychological research to include direct observation of living creatures in natural settings. They also examined how psychology could be applied to areas like education, child rearing, and the work environment.

functionalism

Early school of psychology that emphasized studying the purpose, or function, of behavior and mental experiences.

Both the structuralists and the functionalists thought that psychology should focus on the study of conscious experiences. But the functionalists had very different ideas about the nature of consciousness and how it should be studied. Rather than trying to identify the essential structures of consciousness at a given moment, James saw consciousness as an ongoing stream of mental activity that shifts and changes.

Like structuralism, functionalism no longer exists as a distinct school of thought in contemporary psychology. Nevertheless, functionalism’s twin themes of the importance of the adaptive role of behavior and the application of psychology to enhance human behavior continue to be evident in modern psychology.

WILLIAM JAMES AND HIS STUDENTS

Like Wundt, James profoundly influenced psychology through his students, many of whom became prominent American psychologists. Two of James’s most notable students were G. Stanley Hall and Mary Whiton Calkins.

In 1878, G. Stanley Hall received the first Ph.D. in psychology awarded in the United States. Hall founded the first psychology research laboratory in the United States at Johns Hopkins University in 1883. He also began publishing the American Journal of Psychology, the first U.S. journal devoted to psychology. Most important, in 1892, Hall founded the American Psychological Association and was elected its first president (Anderson, 2012). Today, the American Psychological Association (APA) is the world’s largest professional organization of psychologists, with approximately 150,000 members.

In 1890, Mary Whiton Calkins was assigned the task of teaching experimental psychology at a new women’s college—Wellesley College. Calkins studied with James at nearby Harvard University. She completed all the requirements for a Ph.D. in psychology. However, Harvard refused to grant her the Ph.D. degree because she was a woman and at the time Harvard was not a coeducational institution (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010).

Although never awarded the degree she had earned, Calkins made several notable contributions to psychology. She conducted research in many areas, including dreams, memory, and personality. In 1891, she established a psychology laboratory at Wellesley College. At the turn of the twentieth century, she wrote a well-received textbook, titled Introduction to Psychology. In 1905, Calkins was elected president of the American Psychological Association—the first woman, but not the last, to hold that position.

Just for the record, the first American woman to earn an official Ph.D. in psychology was Margaret Floy Washburn. Washburn was Edward Titchener’s first doctoral student at Cornell University. She strongly advocated the scientific study of the mental processes of different animal species. In 1908, she published an influential text, titled The Animal Mind. Her book summarized research on sensation, perception, learning, and other “inner experiences” of different animal species. In 1921, Washburn became the second woman elected president of the American Psychological Association (Viney & Burlingame-Lee, 2003).

Finally, one of G. Stanley Hall’s notable students was Francis C. Sumner. Sumner was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. in psychology, awarded by Clark University in 1920. After teaching at several southern universities, Sumner moved to Howard University in Washington, D.C. At Howard he published papers on a wide variety of topics and chaired a psychology department that produced more African American psychologists than all other American colleges and universities combined (Guthrie, 2000, 2004). One of Sumner’s most famous students was Kenneth Bancroft Clark. Clark’s research on the negative effects of discrimination was instrumental in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to end segregation in schools (Jackson, 2006). In 1970, Clark became the first African American president of the American Psychological Association (Belgrave & Allison, 2010).

Sigmund Freud: PSYCHOANALYSIS

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that Sigmund Freud was the first psychologist?

Wundt, James, and other early psychologists emphasized the study of conscious experiences. But at the turn of the twentieth century, new approaches challenged the principles of both structuralism and functionalism.

In Vienna, Austria, a physician named Sigmund Freud was developing an intriguing theory of personality based on uncovering causes of behavior that were unconscious, or hidden from the person’s conscious awareness. Freud’s school of thought, called psychoanalysis, emphasized the role of unconscious conflicts in determining behavior and personality. Freud himself was a neurologist, not a psychologist. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis had a strong influence on psychological thinking in the early part of the century.

psychoanalysis

Personality theory and form of psychotherapy that emphasizes the role of unconscious factors in personality and behavior.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality and behavior was based largely on his work with his patients and on insights derived from self-analysis. Freud believed that human behavior was motivated by unconscious conflicts that were almost always sexual or aggressive in nature. Past experiences, especially childhood experiences, were thought to be critical in the formation of adult personality and behavior. According to Freud (1904), glimpses of these unconscious impulses are revealed in everyday life in dreams, memory blocks, slips of the tongue, and spontaneous humor. Freud believed that when unconscious conflicts became extreme, psychological disorders could result.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality also provided the basis for a distinct form of psychotherapy. Many of the fundamental ideas of psychoanalysis continue to influence psychologists and other professionals in the mental health field. We’ll explore Freud’s theory in more depth in Chapter 11, on personality, and Chapter 15, on psychotherapy.

John B. Watson: BEHAVIORISM

The course of psychology changed dramatically in the early 1900s when another approach, called behaviorism, emerged as a dominating force. Behaviorism rejected the emphasis on consciousness promoted by structuralism and functionalism. It also flatly rejected Freudian notions about unconscious influences, claiming that such ideas were unscientific and impossible to test. Instead, behaviorism contended that psychology should focus its scientific investigations strictly on overt behavior—observable behaviors that could be objectively measured and verified.

behaviorism

School of psychology and theoretical viewpoint that emphasizes the study of observable behaviors, especially as they pertain to the process of learning.

Behaviorism is another example of the influence of physiology on psychology. Behaviorism grew out of the pioneering work of a Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov demonstrated that dogs could learn to associate a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, with an automatic behavior, such as reflexively salivating to food. Once an association between the sound of the bell and the food was formed, the sound of the bell alone would trigger the salivation reflex in the dog. Pavlov enthusiastically believed he had discovered the mechanism by which all behaviors were learned.

In the United States, a young, dynamic psychologist named John B. Watson shared Pavlov’s enthusiasm. Watson (1913) championed behaviorism as a new school of psychology. Structuralism was still an influential perspective, but Watson strongly objected to both its method of introspection and its focus on conscious mental processes. As Watson (1924) wrote in his classic book, Behaviorism:

Behaviorism, on the contrary, holds that the subject matter of human psychology is the behavior of the human being. Behaviorism claims that consciousness is neither a definite nor a usable concept. The behaviorist, who has been trained always as an experimentalist, holds, further, that belief in the existence of consciousness goes back to the ancient days of superstition and magic.

The influence of behaviorism on American psychology was enormous. The goal of the behaviorists was to discover the fundamental principles of learning—how behavior is acquired and modified in response to environmental influences. For the most part, the behaviorists studied animal behavior under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

Although Watson left academic psychology in the early 1920s, behaviorism was later championed by an equally forceful proponent—the famous American psychologist B. F. Skinner. Like Watson, Skinner believed that psychology should restrict itself to studying outwardly observable behaviors that could be measured and verified. In compelling experimental demonstrations, Skinner systematically used reinforcement or punishment to shape the behaviorc of rats and pigeons.

Between Watson and Skinner, behaviorism dominated American psychology for almost half a century. During that time, the study of conscious experiences was largely ignored as a topic in psychology (Baars, 2005). In Chapter 5, on learning, we’ll look at the lives and contributions of Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner in greater detail.

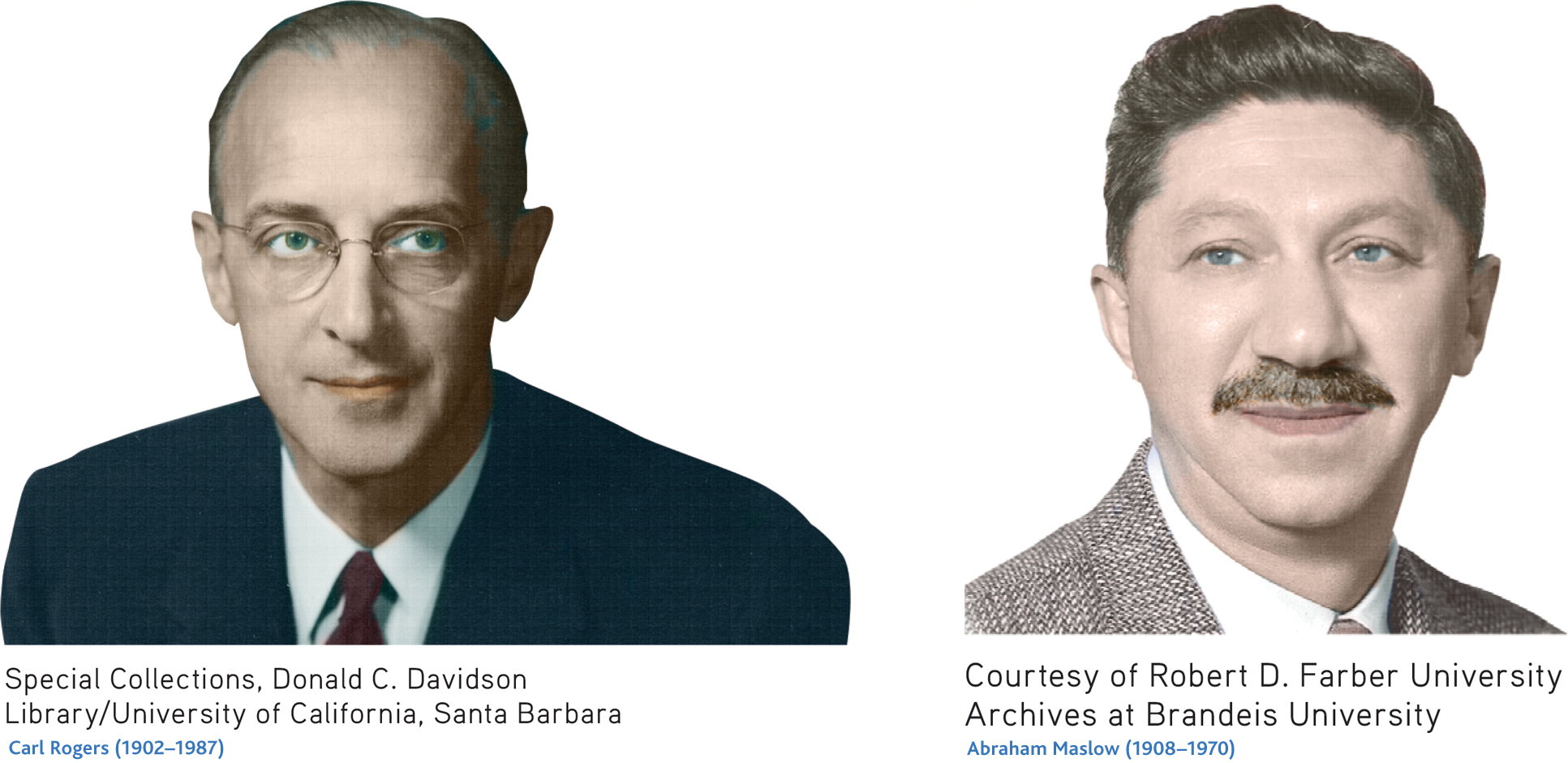

Carl Rogers: HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY

For several decades, behaviorism and psychoanalysis were the perspectives that most influenced the thinking of American psychologists. In the 1950s, a new school of thought emerged, called humanistic psychology. Because humanistic psychology was distinctly different from both psychoanalysis and behaviorism, it was sometimes referred to as the “third force” in American psychology (Waterman, 2013; Watson & others, 2011).

humanistic psychology

School of psychology and theoretical viewpoint that emphasizes each person’s unique potential for psychological growth and self-direction.

Humanistic psychology was largely founded by American psychologist Carl Rogers (Elliott & Farber, 2010). Like Freud, Rogers was influenced by his experiences with his psychotherapy clients. However, rather than emphasizing unconscious conflicts, Rogers emphasized the conscious experiences of his clients, including each person’s unique potential for psychological growth and self-direction. In contrast to the behaviorists, who saw human behavior as being shaped and maintained by external causes, Rogers emphasized self-determination, free will, and the importance of choice in human behavior (Elliott & Farber, 2010; Kirschenbaum & Jourdan, 2005).

Abraham Maslow was another advocate of humanistic psychology. Maslow developed a theory of motivation that emphasized psychological growth, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 8. Like psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology included not only influential theories of personality but also a form of psychotherapy, which we’ll discuss in later chapters.

By briefly stepping backward in time, you’ve seen how the debates among the key thinkers in psychology’s history shaped the development of psychology as a whole. Each of the schools that we’ve described had an impact on the topics and methods of psychological research. As you’ll see throughout this textbook, that impact has been a lasting one. In the next sections, we’ll touch on some of the more recent developments in psychology’s evolution. We’ll also explore the diversity that characterizes contemporary psychology.

CONCEPT REVIEW 1.1

Major Schools in Psychology

Identify the school or approach and the founder associated with each of the following statements.

Question 1.1

| 1. | Psychology should study how behavior and mental processes allow organisms to adapt to their environments. |

School/Approach KSNdR2xfuYgIStMBsBZ/jZvHSBs=

Founder(s) HN7GvmLhsETiAua6E3a74GDmcpA=

Question 1.2

| 2. | Psychology should emphasize each person’s unique potential for psychological growth and self-directedness. |

School/Approach Kp+VwuNegaezAr7kkMZswqVMIRLhtCT/glIY3g==

Founder(s) Ghz/FBtLq5ueqTGbxR5jZg==

Question 1.3

| 3. | Psychology should focus on the elements of conscious experiences, using the method of introspection. |

School/Approach M5PQOH+JfRZlFcQVeqSeobzq+zE=

Founder(s) EJK0WP6Z1xvHthE0inwM+Y4t+YA=

| Lot | x = square footage

(100s of sq. ft.) |

y = sales price

($1000s) |

|---|---|---|

| Harding St. | 75 | 155 |

| Newton Ave. | 125 | 210 |

| Stacy Ct. | 125 | 290 |

| Eastern Ave. | 175 | 360 |

| Second St. | 175 | 250 |

| Sunnybrook Rd. | 225 | 450 |

| Ahlstrand Rd. | 225 | 530 |

| Eastern Ave. | 275 | 635 |

Question 1.4

| 4. | Human behavior is strongly influenced by unconscious sexual and aggressive conflicts. |

School/Approach pA5HAMW2F3S+4UEbAYdm2+Z6pFA=

Founder(s) pQcWg00UhChfkiuA1MQgT7cxOZQ=

Question 1.5

| 5. | Psychology should scientifically investigate observable behaviors that can be measured objectively and should not study consciousness or mental processes. |

School/Approach 1xAzL199JkB48CnwvtSv9Q==

Founder(s) 8hLNpXhbI3JBN2iWi+O/nA==

Test your understanding of The Origins of Psychology with

.

.

1.2 Contemporary Psychology

KEY THEME

As psychology has developed as a scientific discipline, the topics it investigates have become progressively more diverse.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do the perspectives in contemporary psychology differ in emphasis and approach?

How do psychiatry and psychology differ, and what are psychology’s major specialty areas?

Over the past half-century, the range of topics in psychology has become progressively more diverse. And, as psychology’s knowledge base has increased, psychology itself has become more specialized. Rather than being dominated by a particular approach or school of thought, today’s psychologists tend to identify themselves according to (1) the perspective they emphasize in investigating psychological topics and (2) the specialty area in which they have been trained and practice.

Major Perspectives in Psychology

Any given topic in contemporary psychology can be approached from a variety of perspectives. Each perspective discussed here represents a different emphasis or point of view that can be taken in studying a particular behavior, topic, or issue. As you’ll see in this section, the influence of the early schools of psychology is apparent in the first four perspectives that characterize contemporary psychology.

THE BIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

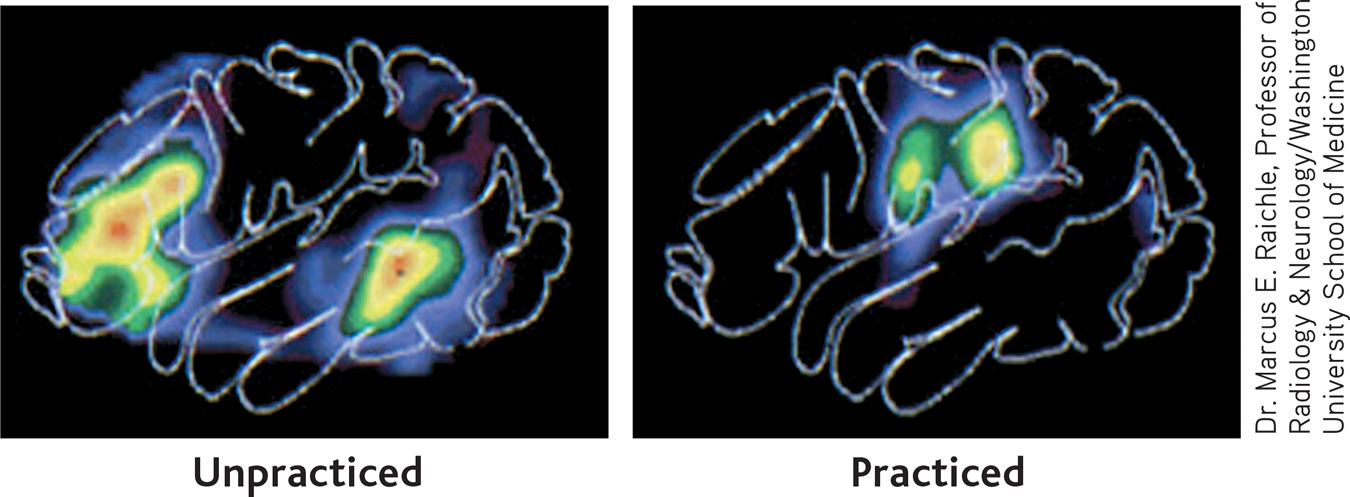

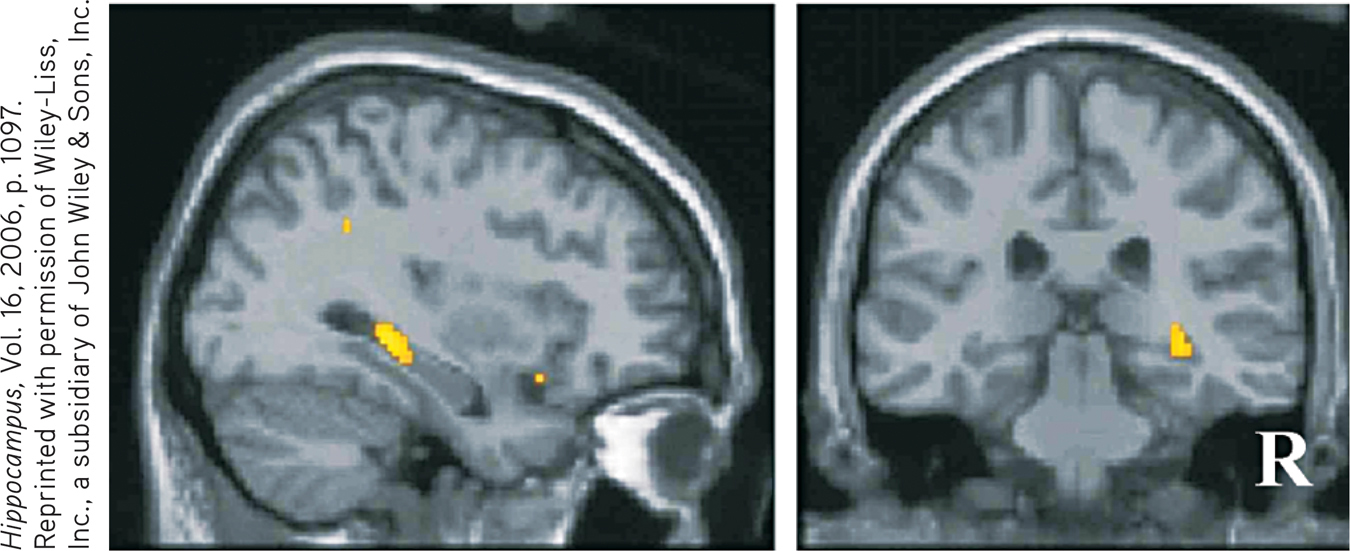

As we’ve already noted, physiology has played an important role in psychology since it was founded. Today, that influence continues, as is shown by the many psychologists who take the biological perspective. The biological perspective emphasizes studying the physical bases of human and animal behavior, including the nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, and genetics. More specifically, neuroscience refers to the study of the nervous system, especially the brain.

neuroscience

The study of the nervous system, especially the brain.

Advances in medicine and technology have reinforced interest in the biological perspective. The discovery of drugs that helped control the symptoms of severe psychological disorders sparked questions about the interaction among biological factors and human behavior, emotions, and thought processes.

Equally important have been technological advances that have allowed psychologists and other researchers to explore the human brain as never before. The development of sophisticated brain-scanning techniques, including the PET scan, MRI scan, and functional MRI (fMRI) scan, allowed neuroscientists to study the structure and activity of the intact, living brain. Later in the chapter, we’ll describe these brain-imaging techniques and identify how psychologists use them as research tools.

THE PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

The key ideas and themes of Freud’s landmark theory of psychoanalysis continue to be important among many psychologists, especially those working in the mental health field. As you’ll see in Chapter 11, on personality, and Chapter 15, on therapies, many of Freud’s ideas have been expanded or modified by his followers. Today, psychologists who take the psychodynamic perspective may or may not follow Freud or take a psychoanalytic approach. However, they do tend to emphasize the importance of unconscious influences, early life experiences, and interpersonal relationships in explaining the underlying dynamics of behavior or in treating people with psychological problems.

THE BEHAVIORAL PERSPECTIVE

Watson and Skinner’s contention that psychology should focus on observable behaviors and the fundamental laws of learning is evident today in the behavioral perspective. Contemporary psychologists who take the behavioral perspective continue to study how behavior is acquired or modified by environmental causes. Many psychologists who work in the area of mental health also emphasize the behavioral perspective in explaining and treating psychological disorders. In Chapter 5, on learning, and Chapter 15, on therapies, we’ll discuss different applications of the behavioral perspective.

THE HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVE

The influence of the work of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow continues to be seen among contemporary psychologists who take the humanistic perspective (Serlin, 2012; Waterman, 2013). The humanistic perspective focuses on the motivation of people to grow psychologically, the influence of interpersonal relationships on a person’s self-concept, and the importance of choice and self-direction in striving to reach one’s potential. Like the psychodynamic perspective, the humanistic perspective is often emphasized among psychologists working in the mental health field. You’ll encounter the humanistic perspective in the chapters on motivation (8), personality (11), and therapies (15).

THE POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PERSPECTIVE

The humanistic perspective’s emphasis on psychological growth and human potential contributed to the recent emergence of a new perspective. Positive psychology is a field of psychological research and theory focusing on the study of positive emotions and psychological states, positive individual traits, and the social institutions that foster those qualities in individuals and communities (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011; Peterson, 2006; Seligman & others, 2005). By studying the conditions and processes that contribute to the optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions, positive psychology seeks to counterbalance psychology’s traditional emphasis on psychological problems and disorders (McNulty & Fincham, 2012).

positive psychology

The study of positive emotions and psychological states, positive individual traits, and the social institutions that foster positive individuals and communities.

Topics that fall under the umbrella of positive psychology include personal happiness, optimism, creativity, resilience, character strengths, and wisdom. Positive psychology is also focused on developing therapeutic techniques that increase personal well-being rather than just alleviating the troubling symptoms of psychological disorders (Snyder & others, 2011). Insights from positive psychology research will be evident in many chapters, including the chapters on motivation and emotion (8); personality (11); stress, health, and coping (13); and therapies (15).

THE COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

During the 1960s, psychology experienced a return to the study of how mental processes influence behavior. Often referred to as “the cognitive revolution” in psychology, this movement represented a break from traditional behaviorism. Cognitive psychology focused once again on the important role of mental processes in how people process and remember information, develop language, solve problems, and think.

The development of the first computers in the 1950s contributed to the cognitive revolution. Computers gave psychologists a new model for conceptualizing human mental processes—human thinking, memory, and perception could be understood in terms of an information-processing model. We’ll consider the cognitive perspective in several chapters, including Chapter 7, on thinking, language, and intelligence. The cognitive perspective has also influenced other areas of psychology, including personality (Chapter 11) and psychotherapy (Chapter 15).

THE CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

More recently, psychologists have taken a closer look at how cultural factors influence patterns of behavior—the essence of the cross-cultural perspective. By the late 1980s, cross-cultural psychology had emerged in full force as large numbers of psychologists began studying the diversity of human behavior in different cultural settings and countries (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011; P. Smith, 2010). In the process, psychologists discovered that some well-established psychological findings were not as universal as they had thought.

For example, one well-established psychological finding was that people exert more effort on a task when working alone than when working as part of a group, a phenomenon called social loafing. First demonstrated in the 1970s, social loafing was a consistent finding in several psychological studies conducted with American and European subjects. But when similar studies were conducted with Chinese participants, the opposite was found to be true (Hong & others, 2008). Chinese participants worked harder on a task when they were part of a group than when they were working alone.

Today, psychologists are keenly attuned to the influence of cultural factors on behavior (Heine, 2010; Henrich & others, 2010). Although many psychological processes are shared by all humans, it’s important to keep in mind that there are cultural variations in behavior. Thus, we have included Culture and Human Behavior boxes throughout this textbook to help sensitize you to the influence of culture on behavior—including your own. We describe cross-cultural psychology in more detail in the Culture and Human Behavior box below.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology?

All cultures are simultaneously very similar and very different.

—Harry Triandis (2005)

People around the globe share many attributes: We all eat, sleep, form families, seek happiness, and mourn losses. Yet the way in which we express our human qualities can vary considerably among cultures. What we eat, where we sleep, and how we form families, define happiness, and express sadness can differ greatly in different cultures.

Culture is a broad term that refers to the attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to another (Cohen, 2009, 2010). When this broad definition is applied to people throughout the world, about 4,000 different cultures can be said to exist. Studying the differences among those cultures and the influences of culture on behavior are the fundamental goals of cross-cultural psychology.

culture

The attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to another.

cross-cultural psychology

Branch of psychology that studies the effects of culture on behavior and mental processes.

A person’s sense of cultural identity is influenced by such factors as ethnic background, nationality, race, religion, and language. As we grow up within a given culture, we learn our culture’s norms, or unwritten rules of behavior. Once those cultural norms are understood and internalized, we tend to act in accordance with them without too much thought. For example, according to the dominant cultural norms in the United States, infants and toddlers are not supposed to routinely sleep in the same bed as their parents. In many other cultures around the world, however, it’s taken for granted that babies will sleep in the same bed as their parents or other adult relatives (Mindell & others, 2010a, b). Members of these other cultures are often surprised and even shocked at the U.S. practice of separating babies from their parents at night. (In the Culture and Human Behavior box in Chapter 9, we discuss this topic at greater length.)

Whether considering sleeping habits or hairstyles, most people share a natural tendency to accept their own cultural rules as defining what’s “normal.” This tendency to use your own culture as the standard for judging other cultures is called ethnocentrism. Although it may be a natural tendency, ethnocentrism can lead to the inability to separate ourselves from our own cultural backgrounds and biases so that we can understand the behaviors of others (Bizumic & others, 2009). Ethnocentrism may also prevent us from being aware of how our behavior has been shaped by our own culture.

ethnocentrism

The belief that one’s own culture or ethnic group is superior to all others and the related tendency to use one’s own culture as a standard by which to judge other cultures.

Some degree of ethnocentrism is probably inevitable, but extreme ethnocentrism can lead to intolerance toward other cultures. If we believe that our way of seeing things or behaving is the only proper one, other ways of behaving and thinking may seem not only foreign, but also ridiculous, inferior, wrong, or immoral.

In addition to influencing how we behave, culture affects how we define our sense of self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998, 2010). For the most part, the dominant cultures of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe can be described as individualistic cultures. Individualistic cultures emphasize the needs and goals of the individual over the needs and goals of the group (Henrich, 2014; Markus & Kitayama, 2010). In individualistic societies, social behavior is more strongly influenced by individual preferences and attitudes than by cultural norms and values. In such cultures, the self is seen as independent, autonomous, and distinctive. Personal identity is defined by individual achievements, abilities, and accomplishments.

individualistic cultures

Cultures that emphasize the needs and goals of the individual over the needs and goals of the group.

In contrast, collectivistic cultures emphasize the needs and goals of the group over the needs and goals of the individual. Social behavior is more heavily influenced by cultural norms and social context than by individual preferences and attitudes (Owe & others, 2013; Talhelm & others, 2014). In a collectivistic culture, the self is seen as being much more interdependent with others. Relationships with others and identification with a larger group, such as the family or tribe, are key components of personal identity. The cultures of Asia, Africa, and Central and South America tend to be collectivistic. According to cross-cultural psychologist Harry Triandis (2005), about two-thirds of the world’s population live in collectivistic cultures.

collectivistic cultures

Cultures that emphasize the needs and goals of the group over the needs and goals of the individual.

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic societies is useful in cross-cultural psychology. Nevertheless, psychologists are careful not to assume that these generalizations are true of every member or every aspect of a given culture (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011). Most cultures are neither completely individualistic nor completely collectivistic, but fall somewhere between the two extremes. Equally important, psychologists recognize that there is a great deal of individual variation among the members of every culture (Heine & Norenzayan, 2006). It’s important to keep that qualification in mind when cross-cultural findings are discussed, as they will be throughout this book.

The Culture and Human Behavior boxes that we have included in this book will help you learn about human behavior in other cultures. They will also help you understand how culture affects your behavior, beliefs, attitudes, and values as well. We hope you will find this feature both interesting and enlightening!

Steve Prezant/Corbis

THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

Evolutionary psychology refers to the application of the principles of evolution to explain psychological processes and phenomena (Buss, 2009, 2011a). The evolutionary perspective reflects a renewed interest in the work of English naturalist Charles Darwin. As noted previously, Darwin’s (1859) first book on evolution, On the Origin of Species, played an influential role in the thinking of many early psychologists.

evolutionary psychology

The application of principles of evolution, including natural selection, to explain psychological processes and phenomena.

The theory of evolution proposes that the individual members of a species compete for survival. Because of inherited differences, some members of a species are better adapted to their environment than are others. Organisms that inherit characteristics that increase their chances of survival in their particular habitat are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics to their offspring. But individuals that inherit less useful characteristics are less likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics. This process reflects the principle of natural selection: The most adaptive characteristics are “selected” and perpetuated in the next generation.

Psychologists who take the evolutionary perspective assume that psychological processes are also subject to the principle of natural selection. As David Buss (2008) writes, “An evolved psychological mechanism exists in the form that it does because it solved a specific problem of survival or reproduction recurrently over evolutionary history.” That is, those psychological processes that helped individuals adapt to their environments also helped them survive, reproduce, and pass those abilities on to their offspring (Confer & others, 2010). However, as you’ll see in later chapters, some of those processes may not necessarily be adaptive in our modern world (Loewenstein, 2010; Tooby & Cosmides, 2008).

Specialty Areas in Psychology

Many people think that psychologists primarily diagnose and treat people with psychological problems or disorders. In fact, psychologists who specialize in clinical psychology are trained in the diagnosis, treatment, causes, and prevention of psychological disorders, leading to a doctorate in clinical psychology.

In contrast, psychiatry is a medical specialty. A psychiatrist has earned a medical degree, either an M.D. or D.O., followed by several years of specialized training in the treatment of mental disorders. As physicians, psychiatrists can hospitalize people, order biomedical therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and prescribe medications. Clinical psychologists are not medical doctors and cannot order medical treatments. However, a few states have passed legislation allowing clinical psychologists to prescribe medications after specialized training (McGrath, 2010).

psychiatry

Medical specialty area focused on the diagnosis, treatment, causes, and prevention of mental and behavioral disorders.

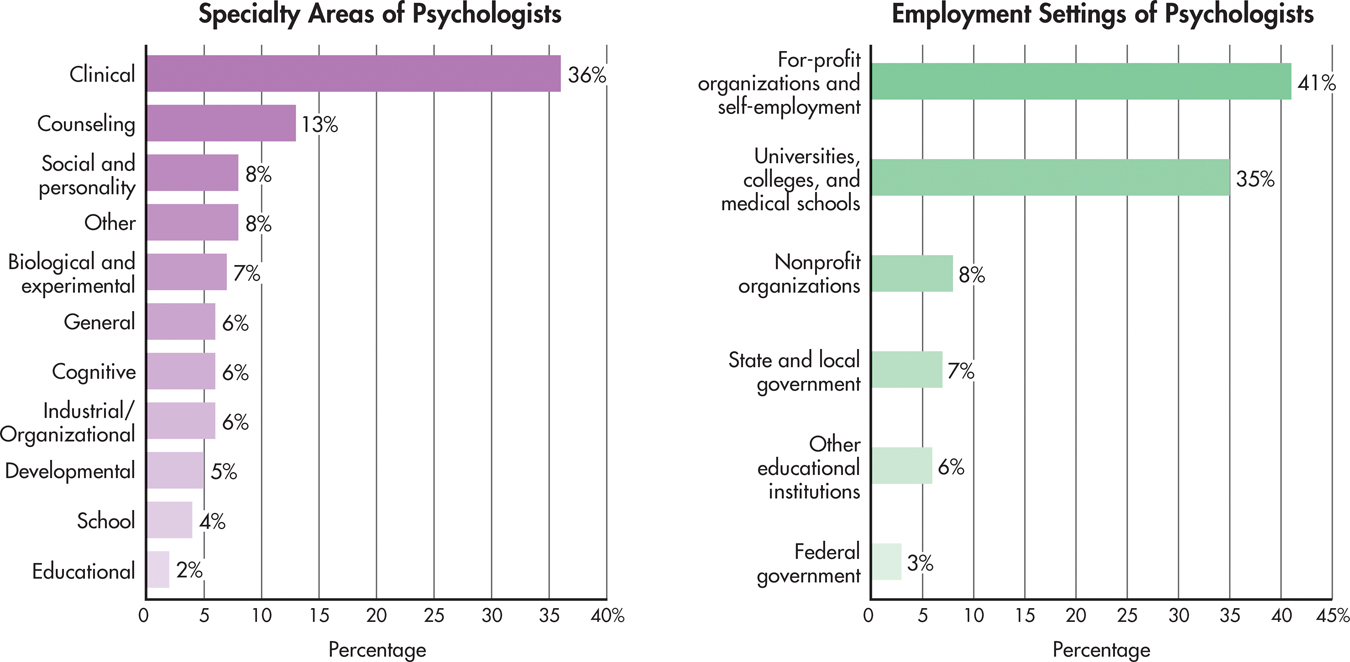

As you’ll learn, contemporary psychology is a very diverse discipline that ranges far beyond the treatment of psychological problems. This diversity is reflected in FIGURE 1.1, which shows the range of specialty areas and employment settings for psychologists. TABLE 1.1 provides a brief overview of psychology’s most important specialty areas.

Source: Data from Finno & others (2006); NSF/NIH/USED/USDA/NEH/ NASA, 2009 Survey of Earned Doctorates.

Major Specialties in Psychology

| Speciality | Major Focus |

|---|---|

| Biological psychology | Relationship between psychological processes and the body’s physical systems; neuroscience refers specifically to the brain and the rest of the nervous system. |

| Clinical psychology | Causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of psychological disorders. |

| Cognitive psychology | Mental processes, including reasoning and thinking, problem solving, memory, perception, mental imagery, and language. |

| Counseling psychology | Helping people adjust, adapt, and cope with personal and interpersonal challenges; improving well-being, alleviating distress and maladjustment, and resolving crises. |

| Developmental psychology | Physical, social, and psychological changes that occur at different ages and stages of the life span. |

| Educational psychology | Applying psychological principles and theories to methods of learning. |

| Experimental psychology | Basic psychological processes, including sensory and perceptual processes, and principles of learning, emotion, and motivation. |

| Health psychology | Psychological factors in the development, prevention, and treatment of illness; stress and coping; promoting health-enhancing behaviors. |

| Industrial/Organizational psychology | The relationship between people and work. |

| Personality psychology | The nature of human personality, including the uniqueness of each person, traits, and individual differences. |

| Social psychology | How an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior are affected by their social environments and by the presence of other people. |

| School psychology | Applying psychological principles and findings in primary and secondary schools. |

| Applied psychology | Applying the findings of basic psychology to diverse areas; examples include sports psychology, media psychology, forensic psychology, rehabilitation psychology. |

CONCEPT REVIEW 1.2

Identifying Perspectives and Specialties

For each of the following psychologists’ statements, fill in the blanks, identifying the perspective and specialty area.

Question 1.6

| 1. | I study brain development in infants. |

Perspective YtE/ZrXYM25+OSu6ASI5jw==

Specialty cqSphXxqzLDh5Yvm+9IwR9DxWoOyN+5PXE6Y9A==

Question 1.7

| 2. | I compare problem-solving strategies in the United States and China. |

Perspective x9t8enkncIKW5ysyKt1VO8y6a50=

Specialty cOIQp1j6AhG9MT4SVSOngmVJ9g2GCBqk

Question 1.8

| 3. | I develop programs to help people modify unhealthy eating habits, focusing on the environmental cues that trigger overeating. |

Perspective LnWOSE1nzddzPyTb1+6tjA==

Specialty nW70JhPy/nUgqmnPgAJPT/ojX9o4E+2c

Question 1.9

| 4. | I investigate the early life experiences of people who seek psychotherapy for symptoms of depression. |

Perspective 5VKMkoOzScQLh47QLOfUZc12J+A=

Specialty 0N29sIDzTc3PVrn8hxtGtb5iM1epbEPL

Question 1.10

| 5. | I compare mate selection patterns in primitive and modern societies. |

Perspective JE9a9CQgz4KR/GaRpTVilA==

Specialty UdbMcNOyO6Dp8W92duT0nuDjH5rWn9Ww

Question 1.11

| 6. | I am currently studying the role that forgiveness plays in family relationships. I want to examine the extent to which forgiveness fosters the development of a healthy family environment and positive individual traits. |

Perspective p0Tc+VUiHGF3MwLNCjc9Vfe+UBbn8ORe

Specialty JlXS9x6dctWzkn2bRZJtkRQHaIfSzpP9uP+xblJRhQhpD5+oUbA831iRCvkD07wHLbUP/Q==

Test your understanding of Contemporary Psychology with

.

.

1.3 The Scientific Method

KEY THEME

The scientific method is a set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that guides all scientists, including psychologists, in conducting research.

KEY QUESTIONS

What assumptions and attitudes are held by psychologists?

What characterizes each step of the scientific method?

How does a hypothesis differ from a theory?

Whatever their approach or specialty, psychologists who do research are scientists. And, like other scientists, they rely on the scientific method to guide their research. The scientific method refers to a set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that guide researchers in creating questions to investigate, in generating evidence, and in drawing conclusions.

scientific method

A set of assumptions, attitudes, and procedures that guide researchers in creating questions to investigate, in generating evidence, and in drawing conclusions.

Like all scientists, psychologists are guided by the basic scientific assumption that events are lawful. When this scientific assumption is applied to psychology, it means that psychologists assume that behavior and mental processes follow consistent patterns. Psychologists are also guided by the assumption that events are explainable. Thus, psychologists assume that behavior and mental processes have a cause or causes that can be understood through careful, systematic study.

Psychologists are also open-minded. They are willing to consider new or alternative explanations of behavior and mental processes. However, their open-minded attitude is tempered by a healthy sense of scientific skepticism. That is, psychologists critically evaluate the evidence for new findings, especially those that seem contrary to established knowledge.

The Steps in the Scientific Method: SYSTEMATICALLY SEEKING ANSWERS

Like any science, psychology is based on verifiable or empirical evidence—evidence that is the result of objective observation, measurement, and experimentation. As part of the overall process of producing empirical evidence, psychologists follow the four basic steps of the scientific method. In a nutshell, these steps are:

Formulate a specific question that can be tested

Design a study to collect relevant data

Analyze the data to arrive at conclusions

Report the results

empirical evidence

Verifiable evidence that is based upon objective observation, measurement, and/or experimentation.

Following the basic guidelines of the scientific method does not guarantee that valid conclusions will always be reached. However, these steps help guard against bias and minimize the chances for error and faulty conclusions. Let’s look at some of the key concepts associated with each step of the scientific method.

STEP 1. FORMULATE A TESTABLE HYPOTHESIS

Once a researcher has identified a question or an issue to investigate, he or she must formulate a hypothesis that can be tested empirically. Formally, a hypothesis is a tentative statement that describes the relationship between two or more variables. A hypothesis is often stated as a specific prediction that can be empirically tested, such as “strong social networks are associated with greater well-being in college students.”

hypothesis

(high-POTH-uh-sis) A tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables; a testable prediction or question.

A variable is simply a factor that can vary, or change. These changes must be capable of being observed, measured, and verified. The psychologist must provide an operational definition of each variable to be investigated. An operational definition defines the variable in very specific terms as to how it will be measured, manipulated, or changed. Operational definitions are important because many of the concepts that psychologists investigate—such as memory, happiness, or stress—can be measured in more than one way.

variable

A factor that can vary, or change, in ways that can be observed, measured, and verified.

operational definition

A precise description of how the variables in a study will be manipulated or measured.

For example, how would you test the hypothesis that “strong social networks are associated with greater well-being in college students”? To test that specific prediction, you would need to formulate an operational definition of each variable. How could you operationally define social networks? Well-being? What could you objectively observe and measure?

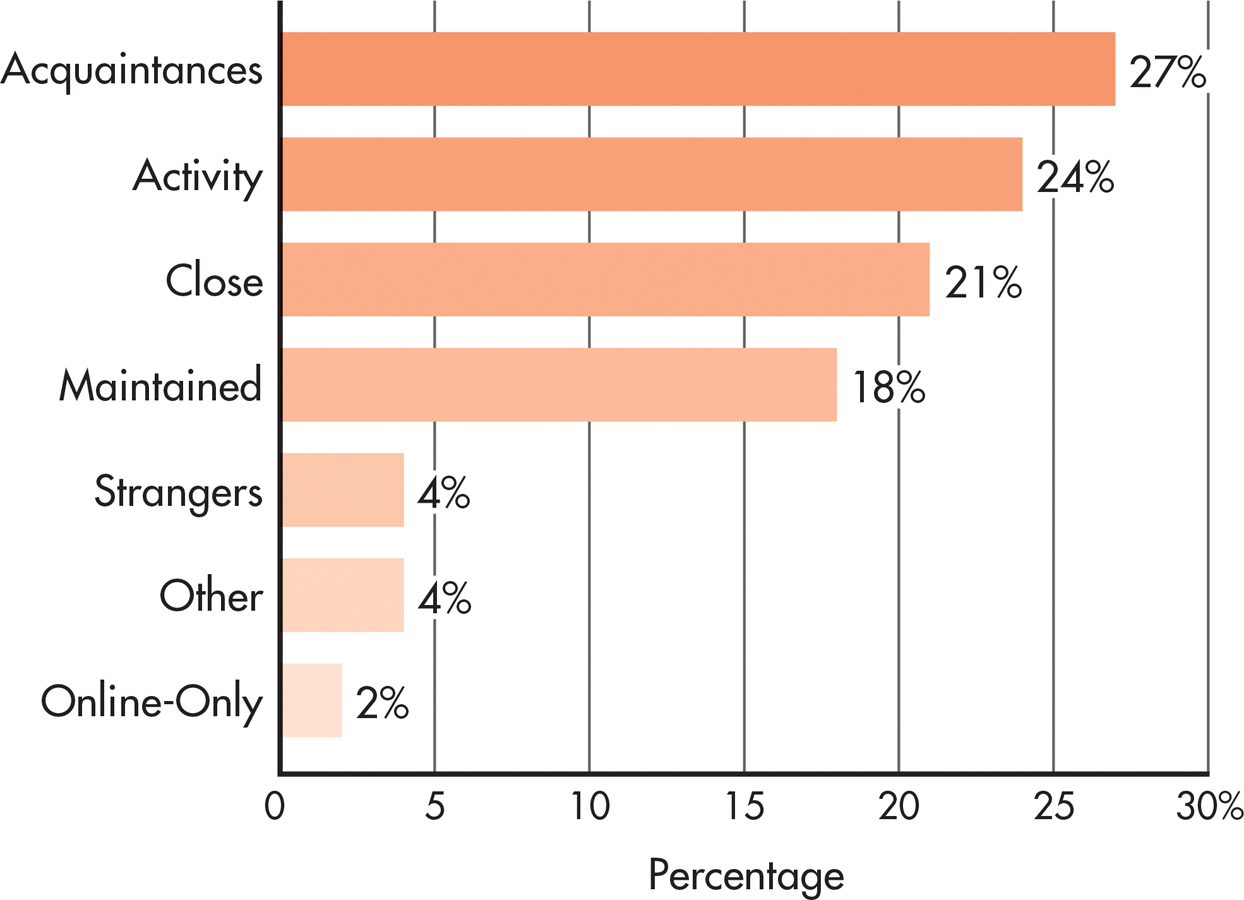

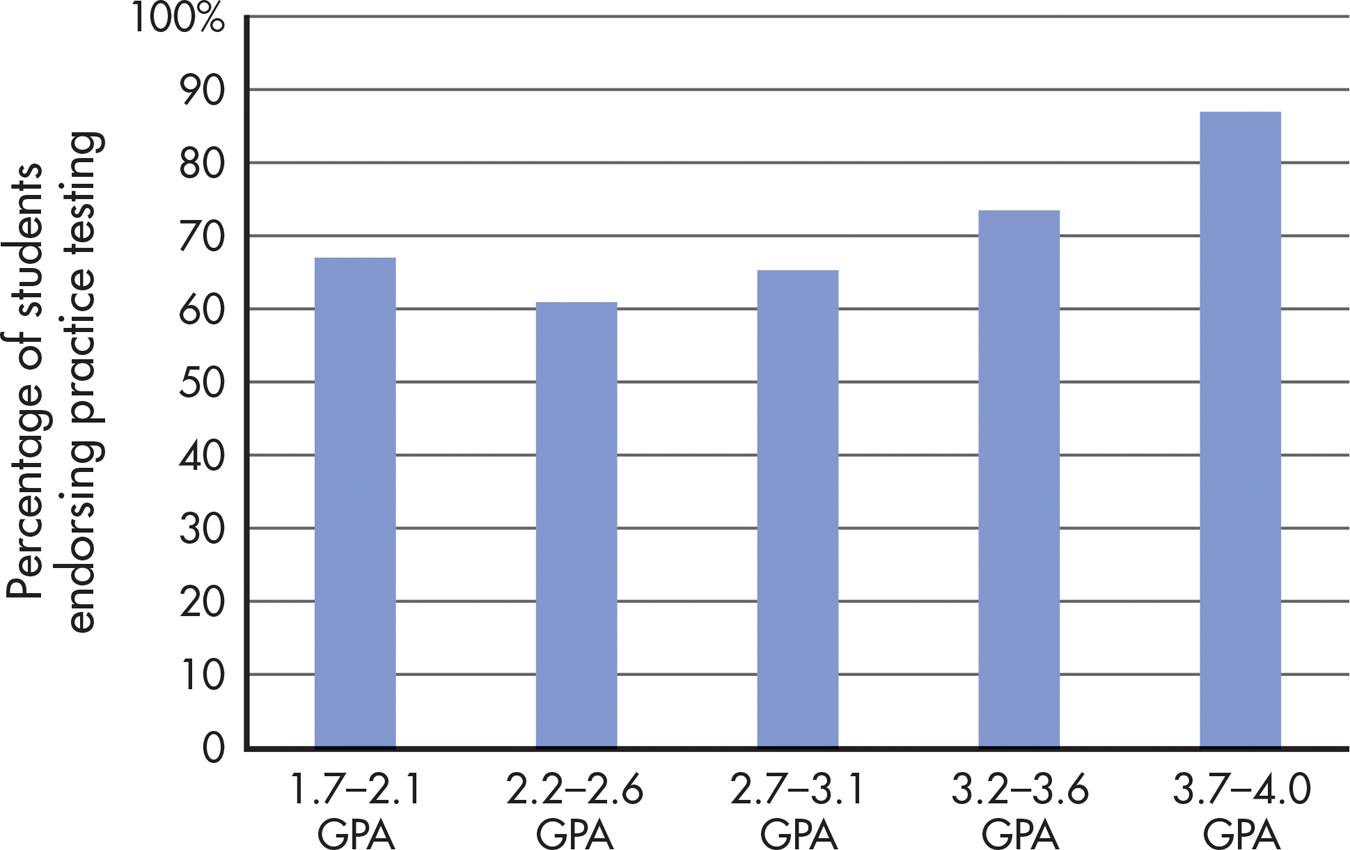

To investigate the impact of social networks on college students, Adriana Manago and her colleagues (2012) used Facebook data. They operationally defined network size as the participant’s number of Facebook friends. They asked participants to classify their Facebook friends into different categories, such as “close friends,” “acquaintances,” and “online” friends. FIGURE 1.2 shows the percentage of each type of friend in the participants’ social networks.

Source: Data from Manago & others (2012).

How was well-being operationally defined? Manago and her colleagues (2012) used a standard scale that measured life satisfaction. Students rated their agreement on a 5-point scale for nine statements like “I have a good life” and “I like the way things are going for me.” And what did Manago and her colleagues find? Students with larger networks were significantly happier with their lives.

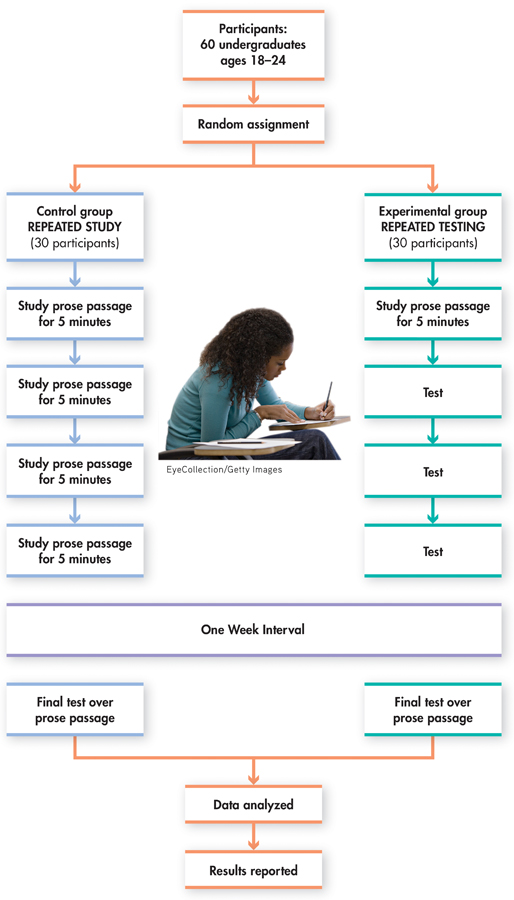

STEP 2. DESIGN THE STUDY AND COLLECT THE DATA

This step involves deciding which research method to use for collecting data. There are two basic types of designs used in research—descriptive and experimental. Each research approach answers different kinds of questions and provides different kinds of evidence.

Descriptive research includes research strategies for observing and describing behavior, including identifying the factors that seem to be associated with a particular phenomenon. The study by Adriana Manago and her colleagues (2012) on social networks and student well-being is just one example of descriptive research. Descriptive research answers the who, what, where, and when kinds of questions about behavior. Who engages in a particular behavior? What factors or events seem to be associated with the behavior? Where does the behavior occur? When does the behavior occur? How often? In the next section, we’ll discuss commonly used descriptive methods, including naturalistic observation, surveys, case studies, and correlational studies.

In contrast, experimental research is used to show that one variable causes change in a second variable. In an experiment, the researcher deliberately varies one factor, then measures the changes produced in a second factor. Ideally, all experimental conditions are kept as constant as possible except for the factor that the researcher systematically varies. Then, if changes occur in the second factor, those changes can be attributed to the variations in the first factor.

STEP 3. ANALYZE THE DATA AND DRAW CONCLUSIONS

Once observations have been made and measurements have been collected, the raw data need to be analyzed and summarized. Researchers use the methods of a branch of mathematics known as statistics to analyze, summarize, and draw conclusions about the data they have collected.

statistics

A branch of mathematics used by researchers to organize, summarize, and interpret data.

Researchers rely on statistics to determine whether their results support their hypotheses. They also use statistics to determine whether their findings are statistically significant. If a finding is statistically significant, it means that the results are not very likely to have occurred by chance. As a rule, statistically significant results confirm the hypothesis. Appendix A provides a more detailed discussion of the use of statistics in psychology research.

statistically significant

A mathematical indication that research results are not very likely to have occurred by chance.

Keep in mind that even though a finding is statistically significant, it may not be practically significant. If a study involves a large number of participants, even small differences among groups of subjects may result in a statistically significant finding. But the actual average differences may be so small as to have little practical significance or importance.

For example, Reynol Junco (2012) surveyed nearly two thousand college students and found a statistically significant relationship between GPA and amount of time spent on Facebook: Students who spent a lot of time on Facebook tended to have lower grades than students who spent less time. However, the practical, real-world significance of this relationship was low: It turned out that a student had to spend 93 minutes per day more than the average of 106 minutes for the increased time to have even a small (.12 percentage points) impact on GPA. So remember that a statistically significant result is simply one that is not very likely to have occurred by chance. Whether the finding is significant in the everyday sense of being important is another matter altogether.

A statistical technique called meta-analysis is sometimes used in psychology to analyze the results of many research studies on a specific topic. Meta-analysis involves pooling the results of several studies into a single analysis. By creating one large pool of data to be analyzed, meta-analysis can help reveal overall trends that may not be evident in individual studies.

meta-analysis

A statistical technique that involves combining and analyzing the results of many research studies on a specific topic in order to identify overall trends.

Meta-analysis is especially useful when a particular issue has generated a large number of studies with inconsistent results. For example, many studies have looked at the factors that predict success in college. British psychologists Michelle Richardson and her colleagues (2012) pooled the results of over 200 research studies investigating personal characteristics that were associated with success in college. “Success in college” was operationally defined as cumulative grade-point average (GPA). They found that motivational factors were the strongest predictor of college success, outweighing test scores, high school grades, and socioeconomic status. Especially important was a trait they called performance self-efficacy, the belief that you have the skills and abilities to succeed at academic tasks. We’ll talk more about self-efficacy in Chapter 8, on motivation and emotion.

STEP 4. REPORT THE FINDINGS

For advances to be made in any scientific discipline, researchers must share their findings with other scientists. In addition to reporting their results, psychologists provide a detailed description of the study itself, including who participated in the study, how variables were operationally defined, how data were analyzed, and so forth.

Describing the precise details of the study makes it possible for other investigators to replicate, or repeat, the study. Replication is an important part of the scientific process. When a study is replicated and the same basic results are obtained again, scientific confidence that the results are accurate is increased. Conversely, if the replication of a study fails to produce the same basic findings, confidence in the original findings is reduced.

replicate

To repeat or duplicate a scientific study in order to increase confidence in the validity of the original findings.

Psychologists present their research at academic conferences or write a paper summarizing the study and submit it to one of the many psychology journals for publication. Before accepting papers for publication, most psychology journals send the paper to other knowledgeable psychologists to review and evaluate. If the study conforms to the principles of sound scientific research and contributes to the existing knowledge base, the paper is accepted for publication.

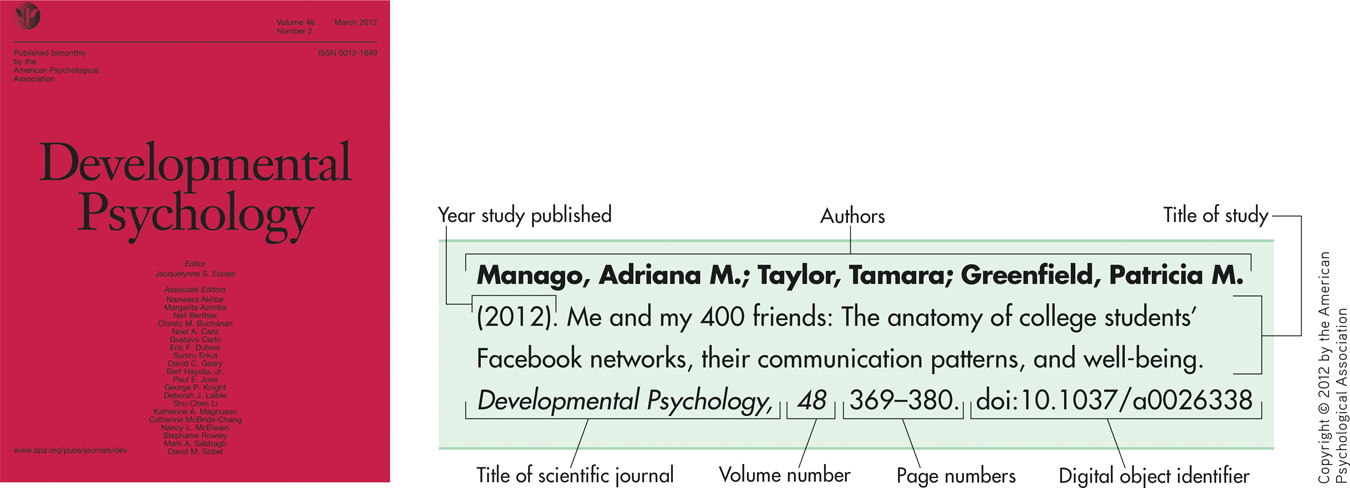

Throughout this text, you’ll see citations that look like the one you encountered in the discussion above on social networks and well-being: “(Manago & others, 2012).” These citations identify the sources of the research and ideas that are being discussed. The citation tells you the author or authors (Manago & others) of the study and the year (2012) in which the study was published. You can find the complete reference in the alphabetized References section at the back of this text. The complete reference lists the authors’ full names, the article title, the journal or book in which the article was published, and the DOI, or digital object identifier. The DOI is a permanent Internet “address” for journal articles and other digital works posted on the Internet.

FIGURE 1.3 shows you how to decipher the different parts of a typical journal reference.

Building Theories: INTEGRATING THE FINDINGS FROM MANY STUDIES

As research findings accumulate from individual studies, eventually theories develop. A theory, or model, is a tentative explanation that tries to account for diverse findings on the same topic. Note that theories are not the same as hypotheses. A hypothesis is a specific question or prediction to be tested. In contrast, a theory integrates and summarizes numerous research findings and observations on a particular topic. Along with explaining existing results, a good theory often generates new predictions and hypotheses that can be tested by further research (Higgins, 2004).

theory

A tentative explanation that tries to integrate and account for the relationship of various findings and observations.

As you encounter different theories, try to remember that theories are tools for explaining behavior and mental processes, not statements of absolute fact. Like any tool, the value of a theory is determined by its usefulness. A useful theory is one that furthers the understanding of behavior, allows testable predictions to be made, and stimulates new research. Often, more than one theory proves to be useful in explaining a particular area of behavior or mental processes, such as the development of personality or the experience of emotion.

It’s also important to remember that theories often reflect the self-correcting nature of the scientific enterprise. In other words, when new research findings challenge established ways of thinking about a phenomenon, theories are expanded, modified, and even replaced. Thus, as the knowledge base of psychology evolves and changes, theories evolve and change to produce more accurate and useful explanations of behavior and mental processes.

While the conclusions of psychology rest on empirical evidence gathered using the scientific method, the same is not true of pseudoscientific claims (J. C. Smith, 2010). As you’ll read in the Science Versus Pseudoscience box below, pseudosciences often claim to be scientific while ignoring the basic rules of science.

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

What Is a Pseudoscience?

The word pseudo means “fake” or “false.” Thus, a pseudoscience is a fake science. More specifically, a pseudoscience is a theory, method, or practice that promotes claims in ways that appear to be scientific and plausible even though supporting empirical evidence is lacking or nonexistent (Matute & others, 2011). Surveys have found that pseudoscientific beliefs are common among the general public (National Science Board, 2010).

pseudoscience

Fake or false science that makes claims based on little or no scientific evidence.

Do you remember Tyler from our Prologue? He wanted to know whether a magnetic bracelet could help him concentrate or improve his memory. We’ll use what we learned about magnet therapy to help illustrate some of the common strategies used to promote pseudosciences.

Magnet Therapy: What’s the Attraction?

The practice of applying magnets to the body to supposedly treat various conditions and ailments is called magnet therapy. Magnet therapy has been around for centuries. Today, Americans spend an estimated $500 million each year on magnetic bracelets, belts, vests, pillows, and mattresses. Worldwide, the sale of magnetic devices is estimated to be $5 billion per year (Winemiller & others, 2005).

The Internet has been a bonanza for those who market products like magnet therapy. Web sites hail the “scientifically proven healing benefits” of magnet therapy for everything from improving concentration and athletic prowess to relieving stress and curing Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia (e.g., Johnston, 2008; Parsons, 2007). Treating pain is the most commonly marketed use of magnet therapy. However, reviews of scientific research on magnet therapy consistently conclude that there is no evidence that magnets can relieve pain (National Standard, 2009: National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2009).

But proponents of magnet therapy, like those of other pseudoscientific claims, use very effective strategies to create the illusion of scientifically validated products or procedures. Each of the ploys below should serve as a warning sign that you need to engage your critical and scientific thinking skills.

Strategy 1: Testimonials rather than scientific evidence

Pseudosciences often use testimonials or personal anecdotes as evidence to support their claims. Although they may be sincere and often sound compelling, testimonials are not acceptable scientific evidence. Testimonials lack the basic controls used in scientific research. Many different factors, such as the simple passage of time, could account for a particular individual’s response.

Strategy 2: Scientific jargon without scientific substance

Pseudoscientific claims are littered with scientific jargon to make their claims seem more credible. An ad may be littered with scientific-sounding terms, such as “bio-magnetic balance” that—when examined—turn out to be meaningless.

Strategy 3: Combining established scientific knowledge with unfounded claims

Pseudosciences often mention well-known scientific facts to add credibility to their unsupported claims. For example, the magnet therapy spiel often starts by referring to the properties of the earth’s magnetic field, the fact that blood contains minerals and iron, and so on. Unfortunately, it turns out that the iron in red blood cells is not attracted to magnets (Ritchie & others, 2012). Established scientific procedures may also be mentioned, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For the record, MRI does not use static magnets, which are the type that are found in magnetic jewelry.

Strategy 4: Irrefutable or nonfalsifiable claims

Consider this claim: “Magnet therapy restores the natural magnetic balance required by the body’s healing process.” How could you test that claim? An irrefutable or nonfalsifiable claim is one that cannot be disproved or tested in any meaningful way. The irrefutable claims of pseudosciences typically take the form of broad or vague statements that are essentially meaningless.

Strategy 5: Confirmation bias

Scientific conclusions are based on converging evidence from multiple studies, not a single study. Pseudosciences ignore this process and instead trumpet the findings of a single study that seems to support their claims. In doing so, they do not mention all the other studies that tested the same thing but yielded results that failed to support the claim. This illustrates confirmation bias—the tendency to seek out evidence that confirms an existing belief while ignoring evidence that contradicts or undermines the belief (J. C. Smith, 2010). When disconfirming evidence is pointed out, it is ignored, rationalized, or dismissed.

confirmation bias

The tendency to seek out evidence that confirms an existing belief while ignoring evidence that might contradict or undermine the belief.

Strategy 6: Shifting the burden of proof

In science, the responsibility for proving the validity of a claim rests with the person making the claim. Many pseudosciences, however, shift the burden of proof to the skeptic. If you express skepticism about a pseudoscientific claim, the pseudoscience advocate will challenge you to disprove their claim.

Strategy 7: Multiple outs

What happens when pseudosciences fail to deliver on their promised benefits? Typically, multiple excuses are offered. Privately, Tyler admitted that he hadn’t noticed any improvement in his ability to concentrate while wearing the bracelet his girlfriend gave him. But his girlfriend insisted that he simply hadn’t worn the bracelet long enough for the magnets to “clear his energy field.” Other reasons given when magnet therapy fails to work:

Magnets act differently on different body parts.

The magnet was placed in the wrong spot.

The magnets were the wrong type, size, shape, etc.

One of our goals in this text is to help you develop your scientific thinking skills so you’re better able to evaluate claims about behavior or mental processes, especially claims that seem farfetched or too good to be true. In this chapter, we’ll look at the scientific methods used to test hypotheses and claims. And in the Science Versus Pseudoscience boxes in later chapters, you’ll see how various pseudoscience claims have stood up to scientific scrutiny. We hope you enjoy this feature!

1.4 Descriptive Research

KEY THEME

Descriptive research is used to systematically observe and describe behavior.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are naturalistic observation and case study research, and why and how are they conducted?

What is a survey, and why is random selection important in survey research?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of each descriptive method?

Descriptive research designs include strategies for observing and describing behavior. Using descriptive research designs, researchers can answer important questions, such as when certain behaviors take place, how often they occur, and whether they are related to other factors, such as a person’s age, ethnic group, or educational level. As you’ll see in this section, descriptive research can provide a wealth of information about behavior, especially behaviors that would be difficult or impossible to study experimentally.

descriptive research

Scientific procedures that involve systematically observing behavior in order to describe the relationship among behaviors and events.

Naturalistic Observation: THE SCIENCE OF PEOPLE− AND ANIMAL-WATCHING

When psychologists systematically observe and record behaviors as they occur in their natural settings, they are using the descriptive method called naturalistic observation. Usually, researchers engaged in naturalistic observation try to avoid being detected by their subjects, whether people or nonhuman animals. The basic goal of naturalistic observation is to detect the behavior patterns that exist naturally—patterns that might not be apparent in a laboratory or if the subjects knew they were being watched.

naturalistic observation

The systematic observation and recording of behaviors as they occur in their natural setting.

!launch!

As you might expect, psychologists very carefully define the behaviors that they will observe and measure before they begin their research. Often, to increase the accuracy of the observations, two or more observers are used. In some studies, observations are recorded so that the researchers can carefully analyze the details of the behaviors being studied.

One advantage of naturalistic observation is that it allows researchers to study human behaviors that cannot ethically be manipulated in an experiment. For example, suppose that a psychologist wants to study bullying behavior in children. It would not be ethical to deliberately create a situation in which one child is aggressively bullied by another child. However, it would be ethical to study bullying by observing aggressive behavior in children on a crowded school playground (Drabick & Baugh, 2010).