The Organization and Ownership of the Book Industry

Compared with the revenues earned by other mass media industries, the steady growth of book publishing has been relatively modest. From the mid-

Ownership Patterns

Like most mass media, commercial publishing is dominated by a handful of major corporations with ties to international media conglomerates. Mergers and consolidations have driven the book industry. For example, one of the largest publishing conglomerates is Germany’s Bertelsmann. Beginning in the late 1970s with its purchase of Dell for $35 million and its 1980s purchase of Doubleday for $475 million, Bertelsmann has been building a publishing dynasty. In 1998, Bertelsmann shook up the book industry by adding Random House, the largest U.S. book publisher, to its fold for $1.4 billion. Bertelsmann’s book company subsidiaries include Ballantine Bantam Dell, Doubleday Broadway, Alfred A. Knopf, and the Random House Publishing Group. In 2013, Random House merged with Penguin Books (owned by Pearson PLC, a British corporation), creating Penguin Random House and gaining control of about one-

| Rank/Publishing Company (Group or Division) | Home Country | Revenue in $ Millions |

| 1 Pearson | U.K. | $9,330 |

| 2 Reed Elsevier | U.K./NL/U.S. | $7,288 |

| 3 Thomson Reuters | U.S. | $5,576 |

| 4 Wolters Kluwer | NL | $4,920 |

| 5 Penguin Random House (Bertelsmann & Pearson) | Germany/U.K. | $3,664 |

| 6 Hachette Livre (Lagardère) | France | $2,851 |

| 7 Holtzbrinck | Germany | $2,222 |

| 8 Grupo Planeta | Spain | $2,161 |

| 9 Cengage (Apax Partners) | U.S./Canada | $1,993 |

| 10 McGraw- |

U.S. | $1,992 |

Table 10.2: TABLE 10.2 WORLD’S TEN LARGEST BOOK PUBLISHERS (REVENUE IN MILLIONS OF DOLLARS), 2014 Data from: “The World’s 56 Largest Book Publishers, 2014,” Publishers Weekly, June 27, 2014, www.publishersweekly.com/

Penguin Random House (jointly owned since 2013 by Bertelsmann and Pearson), Simon & Schuster (owned by CBS), Hachette (owned by French-

The Structure of Book Publishing

BOOK MARKETING

In addition to traditional advertising and in-

A small publishing house may have a staff of a few to twenty people. Medium-

Most publishers employ acquisitions editors to seek out and sign authors to contracts. For fiction, this might mean discovering talented writers through book agents or reading unsolicited manuscripts. For nonfiction, editors might examine manuscripts and letters of inquiry or match a known writer to a project (such as a celebrity biography). Acquisitions editors also handle subsidiary rights for an author—

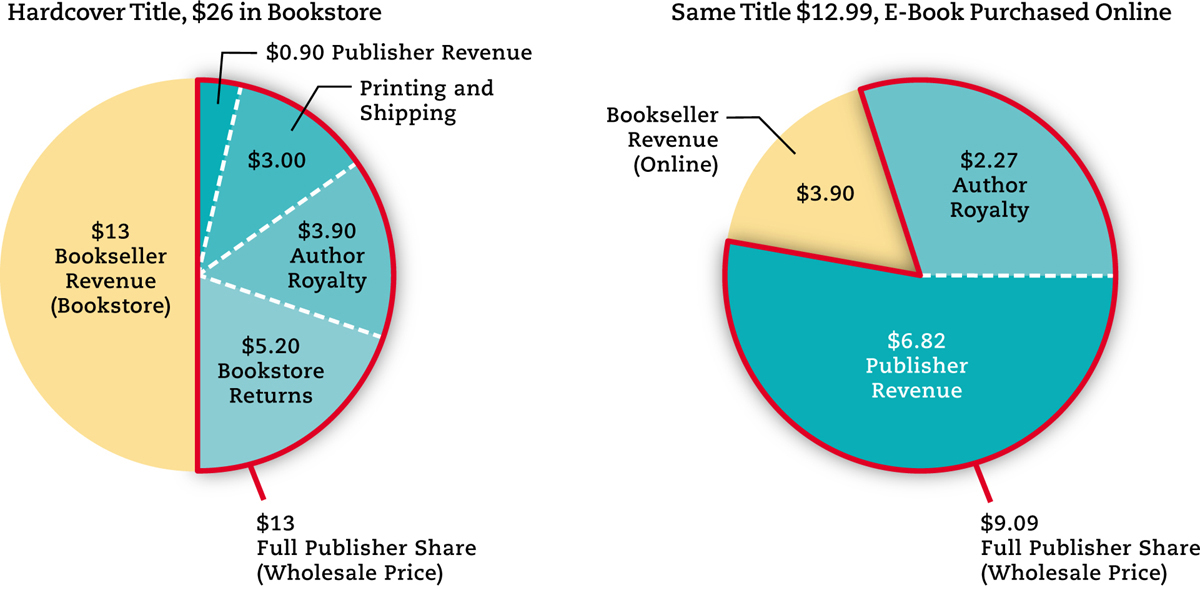

As part of their contracts, writers sometimes receive advance money, an early payment that is subtracted from royalties earned from book sales (see Figure 10.4). Typically, an author’s royalty is between 5 and 15 percent of the net price of the book. New authors may receive little or no advance from a publisher, but commercially successful authors can receive millions. For example, author J. K. Rowling hauled in an estimated $7 million advance from Little, Brown & Company/Hachette for The Casual Vacancy (2012), her first novel after the Harry Potter series. Nationally recognized authors, such as political leaders, sports figures, comedians, or movie stars, can also command large advances from publishers who are banking on the well-

FIGURE 10.4 HOW A BOOK’S REVENUE IS DIVIDED Booksellers are still dependent on printed books, but e-

After a contract is signed, the acquisitions editor may turn the book over to a developmental editor, who provides the author with feedback, makes suggestions for improvements, and, in educational publishing, obtains advice from knowledgeable members of the academic community. If a book is illustrated, editors work with photo researchers to select photographs and pieces of art. Then the production staff enters the picture. While copy editors attend to specific problems in writing or length, production and design managers work on the look of the book, making decisions about type style, paper, cover design, and layout.

Simultaneously, plans are under way to market and sell the book. Decisions need to be made concerning the number of copies to print, ways to reach potential readers, and costs for promotion and advertising. For trade books and some scholarly books, publishing houses may send advance copies of a book to appropriate magazines and newspapers with the hope of receiving favorable reviews that can be used in promotional material. Prominent trade writers typically have book signings and travel the radio and TV talk-

To help create a best-

Selling Books: Brick-

Traditionally, the final part of the publishing process involves the business and order fulfillment stages—

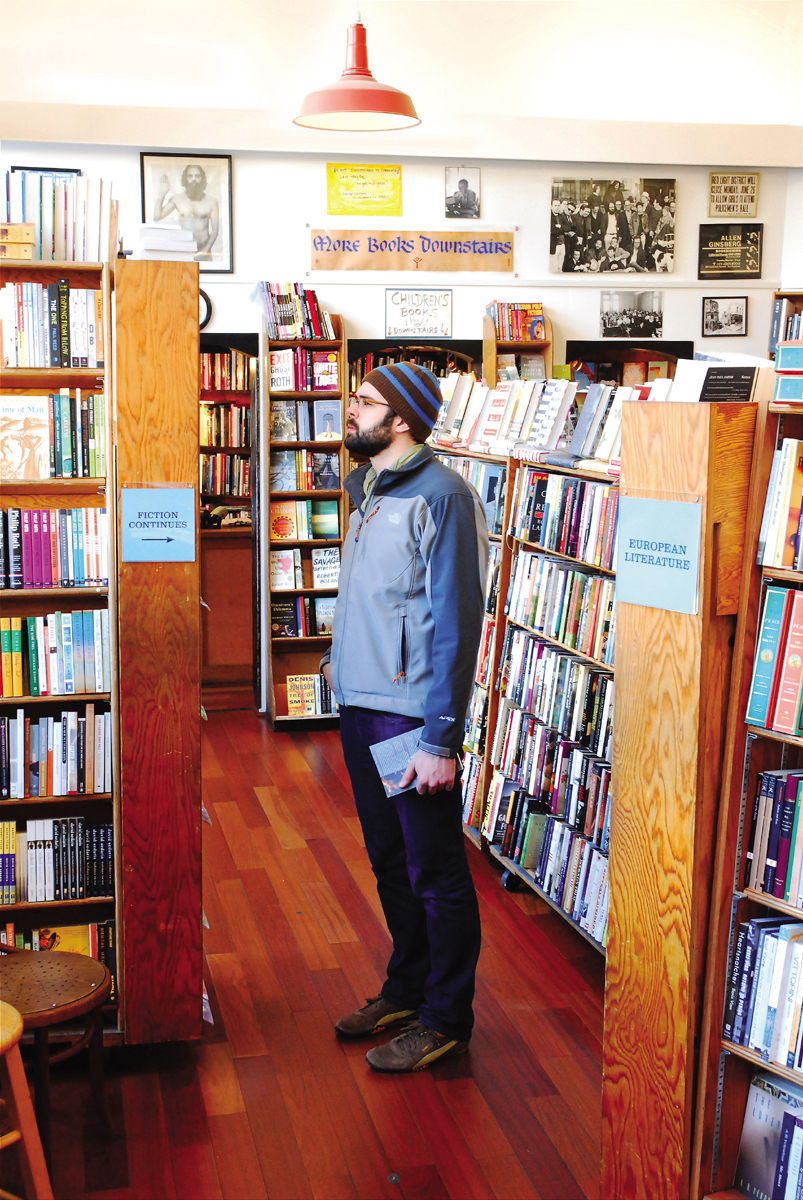

INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORES

City Lights Books in San Francisco is both an independent bookstore and an independent publisher, publishing nearly two hundred titles since launching in 1955, including poet Allen Ginsberg’s revolutionary work Howl. Customers from around the world now come to browse through the landmark store’s three floors and to see the place where beatniks like Ginsberg got their start. © James Kirkikis/age footstock

Today, about 15,000 outlets sell books in the United States, including traditional bookstores, department stores, drugstores, used-

The rise of book superstores (and later, online bookstores) severely cut into independent bookstore business, which dropped from a 31 percent market share in 1991 to 4.3 percent by 2011.19 The number of independent bookstores dropped from 5,100 in 1991 to about 1,900 today. Independent bookstores and superstore chains are being squeezed from multiple sides: online and e-

Book clubs and mail-

The Book-

Mail-

Selling Books Online

Since the late 1990s, online booksellers have created an entirely new book distribution system on the Internet. The strength of online sellers lies in their convenience and low prices, and especially their ability to offer backlist titles and the works of less famous authors that retail stores aren’t able to carry on their shelves. Online customers are also drawn to the interactive nature of these sites, which allow readers to post their own book reviews, read those of fellow customers, and receive book recommendations based on book searches and past purchases.

The trailblazer is Amazon, established in 1995 by then thirty-

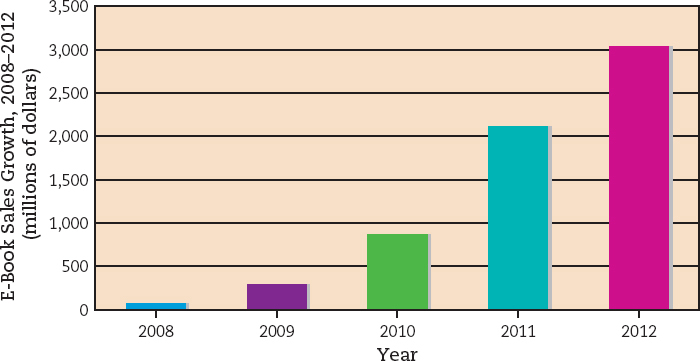

But Amazon’s bigger objective for the book industry was to transform the entire industry itself, from one based on bound paper volumes to one based on digital files. The introduction of the Kindle in 2007 made Amazon the fastest book delivery system in the world. Instead of going to a bookstore or ordering from Amazon and waiting for the book to be delivered in a box, one could buy a book in a few seconds from the Amazon store (see Figure 10.5). Amazon quickly grew to control 90 percent of the e-

FIGURE 10.5 E-

Amazon’s price slashing caused most of the major trade book publishing corporations to endorse Apple’s agency-

Amazon’s biggest rivals in the digital book business are those with their own tablet devices. Apple has its iBook Store, which is available for iPads and iPhones through an app in the iTunes store. Google Play, Google’s digital media store, combines newly released and backlist books, along with the out-

Independent bookstores are an increasingly rare breed in the retail book industry. But to support independents, the American Booksellers Association created IndieCommerce, an e-

Alternative Voices

FIFTY SHADES OF GREY began its unlikely success story as Twilight fan fiction—

Even though the book industry is dominated by large book publishers and one big online retailer (Amazon), there are still alternative options for both publishing and selling books. One alternative idea is to make books freely available to everyone. This idea is not a new one—

One Internet source, NewPages, is working on another alternative to conglomerate publishing and chain bookselling by trying to bring together a vast array of alternative and university presses, independent bookstores, and guides to literary and alternative magazines. The site’s listing of independent publishers, for example, includes hundreds, mostly based in the United States and Canada, ranging from Academy Chicago Publishers (which publishes a range of fiction and nonfiction books) to Zephyr Press (which “publishes literary titles that foster a deeper understanding of cultures and languages”).

Finally, because e-

Sometimes self-