Persuasive Techniques in Contemporary Advertising

Ad agencies and product companies often argue that the main purpose of advertising is to inform consumers about available products in a straightforward way. Most consumer ads, however, merely create a mood or tell stories about products without revealing much else. A one-

Conventional Persuasive Strategies

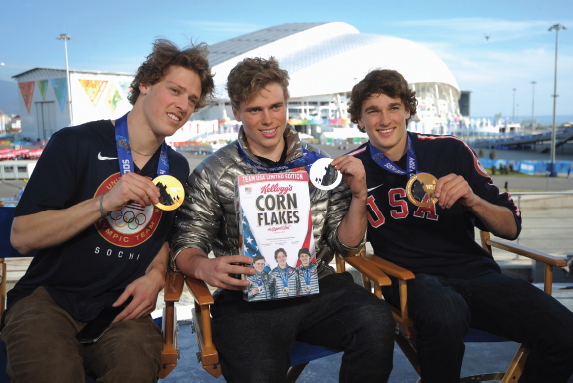

FAMOUS-

Olympic glory comes not just with medals but with endorsement deals. Members of the USA’s slopestyle skiing team, at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, appeared on a special-

One of the most frequently used advertising approaches is the famous-

Another technique, the plain-

By contrast, the snob-

Another approach, the bandwagon effect, points out in exaggerated claims that everyone is using a particular product. Brands that refer to themselves as “America’s favorite” or “the best” imply that consumers will be left behind if they ignore these products. A different technique, the hidden-

A final ad strategy, used more in local TV and radio campaigns than in national ones, has been labeled irritation advertising: creating product-

CASE STUDY

Hey, Super Bowl Sponsors: Your Ads Are Already Forgotten

by Eric Chemi

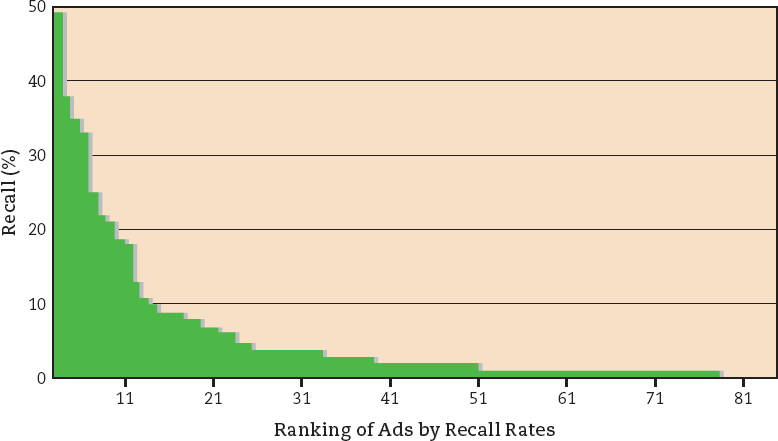

With Super Bowl ad rates averaging $4 million per 30 seconds, total spending for commercials during this year’s game approached $300 million. Here’s the problem: Most of those commercials have already been forgotten. A survey of audience respondents conducted by marketing-

When asked to recall as many companies as possible that had ads during the big game, the average viewer in the survey could name only 5.4 brands. With more than 50 companies buying ads, that means less than 10 percent were recalled. The top winners were Budweiser, Doritos, Coca-

Daniel Goldstein, Db5’s chief strategy officer, is a former ad executive who has worked on several major Super Bowl campaigns (Pepsi, Doritos, Visa). He says everybody is trying to copy the one-

Some trends could have made a difference. Consistency may have been a factor; the most-

The mathematical question for companies: Is 10 percent recall among 100 million people worth $4 million? With the increase of media fragmentation, there are so few opportunities to reach so many viewers at once. Goldstein says that this is not a knock against the Super Bowl as a platform for advertisers, but rather a signal that advertisers should not waste such a big opportunity for which they paid big bucks. The one trend that does seem to work is consistently showing up year after year, making the money a worthwhile investment in the long run. If companies want to go big, they should be going big every year.

Source: Eric Chemi, “Hey, Super Bowl Sponsors: Your Ads Are Already Forgotten,” Bloomberg Businessweek, February 3, 2014, www.businessweek.com/

The Association Principle

Historically, American car advertisements have shown automobiles in natural settings—

This type of advertising exemplifies the association principle, a widely used persuasive technique that associates a product with a positive cultural value or image even if it has little connection to the product. For example, many ads displayed visual symbols of American patriotism in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in an attempt to associate products and companies with national pride. Media critic Leslie Savan noted that in trying “to convince us that there’s an innate relationship between a brand name and an attitude,” advertising may associate products with nationalism, happy families, success at school or work, natural scenery, freedom, or humor.23

One of the more controversial uses of the association principle has been the linkage of products to stereotyped caricatures of women. In numerous instances, women have been portrayed either as sex objects or as clueless housewives who, during many a daytime TV commercial, need the powerful off-

Another popular use of the association principle is to claim that products are “real” and “natural”—possibly the most familiar adjectives associated with advertising. For example, Coke sells itself as “the real thing,” and the cosmetics industry offers synthetic products that promise to make women look “natural.” The adjectives real and natural saturate American ads yet almost always describe processed or synthetic goods. Green marketing has a similar problem, as it is associated with goods and services that aren’t always environmentally friendly.

Philip Morris’s Marlboro brand has used the association principle to completely transform its product image. In the 1920s, Marlboro began as a fashionable women’s cigarette. Back then, the company’s ads equated smoking with a sense of freedom, attempting to appeal to women who had just won the right to vote. Marlboro, though, did poorly as a women’s product, and new campaigns in the 1950s and 1960s transformed the brand into a man’s cigarette. Powerful images of active, rugged men dominated the ads. Often, Marlboro associated its product with nature, displaying an image of a lone cowboy roping a calf, building a fence, or riding over a snow-

Disassociation as an Advertising Strategy

As a response to corporate mergers and public skepticism toward impersonal and large companies, a disassociation corollary emerged in advertising. The nation’s largest winery, Gallo, pioneered the idea in the 1980s by establishing a dummy corporation, Bartles & Jaymes, to sell jug wine and wine coolers, thereby avoiding the use of the Gallo corporate image in ads and on its bottles. The ads featured Frank and Ed, two low-

In the 1990s, General Motors also used the disassociation strategy, according to the same BusinessWeek report. Reeling from a declining corporate reputation, GM tried to package the Saturn as “a small-

Advertising as Myth and Story

Another way to understand ads is to use myth analysis, which provides insights into how ads work at a general cultural level. Here, the term myth does not refer simply to an untrue story or outright falsehood. Rather, myths help us define people, organizations, and social norms. According to myth analysis, most ads are narratives with stories to tell and social conflicts to resolve. Three common mythical elements are found in many types of ads:

- Ads incorporate myths in mini-

story form, featuring characters, settings, and plots. - Most stories in ads involve conflicts, pitting one set of characters or social values against another.

- Such conflicts are negotiated or resolved by the end of the ad, usually by applying or purchasing a product. In advertising, the product and those who use it often emerge as the heroes of the story.

Even though the stories that ads tell are usually compressed into thirty seconds or onto a single page, they still include the traditional elements of narrative. For instance, many SUV ads ask us to imagine ourselves driving out into the raw, untamed wilderness, to a quiet, natural place that only, say, a Jeep can reach. The audience implicitly understands that the SUV can somehow, almost magically, take us out of our fast-

Most advertisers do not expect consumers to accept without question the stories or associations they make in ads. As media scholar Michael Schudson observed in his book Advertising: The Uneasy Persuasion, they do not “make the mistake of asking for belief.”26 Instead, ads are most effective when they create attitudes and reinforce values. Then they operate like popular fiction, encouraging us to suspend our disbelief. Although most of us realize that ads create a fictional world, we often get caught up in their stories and myths. Indeed, ads often work because the stories offer comfort about our deepest desires and conflicts—

Product Placement

PRODUCT PLACEMENT in movies and television is more prevalent than ever. On television, placement is often most visible in reality shows, while scripted series and films tend to be more subtle—

Product companies and ad agencies have become adept in recent years at product placement: strategically placing ads or buying space in movies, TV shows, comic books, video games, blogs, and music videos so that products appear as part of a story’s set environment (see “Examining Ethics: Brand Integration, Everywhere” on page 398). For example, in 2009, Starbucks became a naming sponsor of MSNBC’s show Morning Joe—which now includes “Brewed by Starbucks” in its logo. In 2013, the Superman movie Man of Steel had the most product placements ever for a film up to that time, with two-

For many critics, product placement has gotten out of hand. What started out as subtle appearances in realistic settings—

In 2005, watchdog organization Commercial Alert asked both the FTC and the FCC to mandate that consumers be warned about product placement on television. The FTC rejected the petition, whereas the FCC proposed product placement rules but had still not approved them by the fall of 2014. In contrast, the European Union recently approved product placement for television but requires programs to alert viewers of such paid placements. In Britain, for example, the letter P must appear in the corner of the screen at commercial breaks and at the beginning and end of a show to signal product placements.27

EXAMINING ETHICS

Brand Integration, Everywhere

How clear should the line be between media content and media sponsors? Generations ago, this question was a concern mainly for newspapers, which worked to erect a “firewall” between the editorial and the business sides of their organizations, meant to prevent advertising concerns from creeping into articles and opinions. But early television and radio shows welcomed advertisers’ sponsorship of programs—

Today, however, advertisers have found new ways to cut through the clutter and put their messages right in the midst of media content.

In television, getting product placements (also known as “brand integration”) during shows is much more desirable than running traditional ads. Reality TV programming, which can be structured around products and services, is especially saturated with brand integration. In fact, such episodes contain an average of 19 minutes and 42 seconds of brand integration appearances per hour. This is more than the time allotted for network TV commercials per hour and nearly three times the amount of brand appearances in scripted programs (6 minutes and 59 seconds).1 For example, The Biggest Loser chronicles the weight losses of its contestants, who work out at 24 Hour Fitness, one of the program’s sponsors, and eat food from General Mills and Subway, two other advertisers.2

UP IN THE AIR featured two major companies: Hilton Hotels and American Airlines (shown). Paramount Pictures/Photofest

On the movie screen, a single product placement deal can translate into revenues ranging from several hundred thousand to millions of dollars. Sometimes the placements help fund production costs. Brandchannel, however, reported that placement in movies declined in 2013 to its lowest level since 2001, with an average of 9.1 products placed in all movies that ranked No. 1 at the box office. Brandchannel awarded Budweiser the 2013 Award for Overall Product Placement: “Budweiser appeared in nearly one-

Now, digital technology makes it even easier to put product placements in visual media. Movies, TV shows, and video games can add or delete product placements; advertising can even be digitally integrated into older media that didn’t originally include product placement. On the Internet, some bloggers and Twitter users write posts on topics or products because they’ve been paid or given gifts to do so.

The rules on disclosure for product placements are weak or nonexistent. Television credits usually include messages about “promotional consideration,” which means there was some paid product integration, but otherwise, there are no warnings to the viewers. Movies have similar standards. The Writers Guild of America has criticized the practice, arguing that it “forces content creators to become ad writers.”4 In fact, some writers say that it is easier to get a studio to buy a script or finance a project if brand integrations are already secured.

In contrast, the Federal Trade Commission requires bloggers to disclose paid sponsorships or posts, but it’s not yet clear how well product placements on the Internet are being monitored. In newspapers, where the “firewall” remains important, the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics calls for journalism to “distinguish news from advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two.” For the rest of the media, however, such hybrids are increasingly embraced as a common and effective form of advertising.

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

The Branded You

To what extent are you influenced by brands?

1 DESCRIPTION. Take a look around your home or dormitory room and list all the branded products you’ve purchased, including food, electronics, clothes, shoes, toiletries, and cleaning products.

2 ANALYSIS. Now organize your branded items into categories. For example, how many items of clothing are branded with athletic, university, or designer logos? What patterns emerge, and what kind of psychographic profile do these brands suggest about you?

3 INTERPRETATION. Why did you buy each particular product? Was it because you thought it was of superior quality? Because it was cheaper? Because your parents used this product (so it was tried, trusted, and familiar)? Because it made you feel a certain way about yourself and you wanted to project this image toward others? Have you ever purchased items without brands or removed logos once you bought the product? Why?

4 EVALUATION. As you become more conscious of our branded environment (and your participation in it), what is your assessment of U.S. consumer culture? Is there too much conspicuous branding? What is good and bad about the ubiquity of brand names in our culture? How does branding relate to the common American ethic of individualism?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Visit Adbusters (www.adbusters.org) and read about action projects that confront commercialism, including Buy Nothing Day, Media Carta, TV Turnoff, the Culturejammers Network, the Blackspot nonbrand sneaker, and Unbrand America. Also visit the home page for the advocacy organization Commercial Alert (www.commercialalert.org) to learn about the most recent commercial incursions into everyday life and what can be done about them. Or write a letter to a company about a product or ad that you think is a problem. How does the company respond?