Commercial Speech and Regulating Advertising

ADBUSTERS MEDIA FOUNDATION

This nonprofit organization based in Canada says its spoof ads, like the one shown here, are designed to “put out a better product and beat the corporations at their own game” (see www.adbusters.org). Besides satirizing the advertising appeals of the fashion, tobacco, alcohol, and food industries, the Adbusters Media Foundation sponsors Buy Nothing Day, an anticonsumption campaign that annually falls on the day after Thanksgiving—

In 1791, Congress passed and the states ratified the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, promising, among other guarantees, to “make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” Over time, we have developed a shorthand label for the First Amendment, misnaming it the free-

Whereas freedom of speech refers to the right to express thoughts, beliefs, and opinions in the abstract marketplace of ideas, commercial speech is about the right to circulate goods, services, and images in the concrete marketplace of products. For most of the history of mass media, only very wealthy citizens established political parties, and multinational companies could routinely afford to purchase speech that reached millions. The Internet, however, has helped to level that playing field. Political speech, like a cleverly edited mash-

Although the mass media have not hesitated to carry product and service-

Critical Issues in Advertising

In his 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard expressed concern that advertising was manipulating helpless consumers, attacking our dignity, and invading “the privacy of our minds.”28 According to this view, the advertising industry was all-

One of the most disastrous campaigns ever featured the now-

As these examples illustrate, most people are not easily persuaded by advertising. Over the years, studies have suggested that between 75 and 90 percent of new consumer products typically fail because they are not embraced by the buying public.30 But despite public resistance to many new products, the ad industry has made contributions, including raising the American standard of living and financing most media industries. Yet serious concerns over the impact of advertising remain. Watchdog groups worry about the expansion of advertising’s reach, and critics continue to condemn ads that stereotype or associate products with sex appeal, youth, and narrow definitions of beauty. Some of the most serious concerns involve children, teens, and health.

Children and Advertising

Children and teenagers, living in a culture dominated by TV ads, are often viewed as “consumer trainees.” For years, groups such as Action for Children’s Television (ACT) worked to limit advertising aimed at children. In the 1980s, ACT fought particularly hard to curb program-

In addition, parent groups have worried about the heavy promotion of products like sugarcoated cereals during children’s programs. Pointing to European countries, where children’s advertising is banned, these groups have pushed to minimize advertising directed at children. Congress, hesitant to limit the protection that the First Amendment offers to commercial speech, and faced with lobbying by the advertising industry, has responded weakly. The Children’s Television Act of 1990 mandated that networks provide some educational and informational children’s programming, but the act has been difficult to enforce and has done little to restrict advertising aimed at kids.

Because children and teenagers influence nearly $500 billion a year in family spending—

Advertising in Schools

A controversial development in advertising was the introduction of Channel One into thousands of schools during the 1989–

Over the years, the National Dairy Council and other organizations have also used schools to promote products, providing free filmstrips, posters, magazines, folders, and study guides adorned with corporate logos. Teachers, especially in underfunded districts, have usually been grateful for the support. Early on, however, Channel One was viewed as a more intrusive threat, violating the implicit cultural border between an entertainment situation (watching commercial television) and a learning situation (going to school). One study showed that schools with a high concentration of low-

Texas and Ohio contain the highest concentrations of Channel One contracts, but many individual school districts and some state systems, including New York and California, have banned Channel One News. These school systems have argued that Channel One provides students with only slight additional knowledge about current affairs, and fear that students deem the products advertised—

Health and Advertising

AS AMERICAN OBESITY CONTINUES TO RISE, ads touting fast food and soft drinks have been countered by health advocacy, as in this ad on the New York City subway warning riders about the sugar content of their morning coffee drinks. © 2012 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene/Elk Studios

Eating Disorders. Advertising has a powerful impact on the standards of beauty in our culture. A long-

If advertising has been criticized for promoting skeleton-

Tobacco. One of the most sustained criticisms of advertising is its promotion of tobacco consumption. Opponents of tobacco advertising have become more vocal in the face of grim statistics: Each year, an estimated 400,000 Americans die from diseases related to nicotine addiction and poisoning. Tobacco ads disappeared from television in 1971, under pressure from Congress and the FCC. However, over the years, numerous ad campaigns have targeted teenage consumers of cigarettes. In 1988, for example, R. J. Reynolds, a subdivision of RJR Nabisco, updated its Joe Camel cartoon character, outfitting him with hipper clothes and sunglasses. Spending $75 million annually, the company put Joe on billboards and store posters and in sports stadiums and magazines. One study revealed that before 1988, fewer than 1 percent of teens under age eighteen smoked Camels. After the ad blitz, however, 33 percent of this age group preferred Camels.

In addition to young smokers, the tobacco industry has targeted other groups. In the 1960s, for instance, the advertising campaigns for Eve and Virginia Slims cigarettes (reminiscent of ads during the suffrage movement in the early 1900s) associated their products with women’s liberation, equality, and slim fashion models. And in 1989, Reynolds introduced a cigarette called Uptown, targeting African American consumers. The ad campaign fizzled due to public protests by black leaders and government officials. When these leaders pointed to the high concentration of cigarette billboards in poor urban areas and the high mortality rates among black male smokers, the tobacco company withdrew the brand.

The government’s position regarding the tobacco industry began to change in the mid-

The agreement’s provisions banned cartoon characters in advertising, thus ending the use of the Joe Camel character; prohibited the industry from targeting young people in ads and marketing and from giving away free samples, tobacco-

LIFESTYLE AD APPEALS

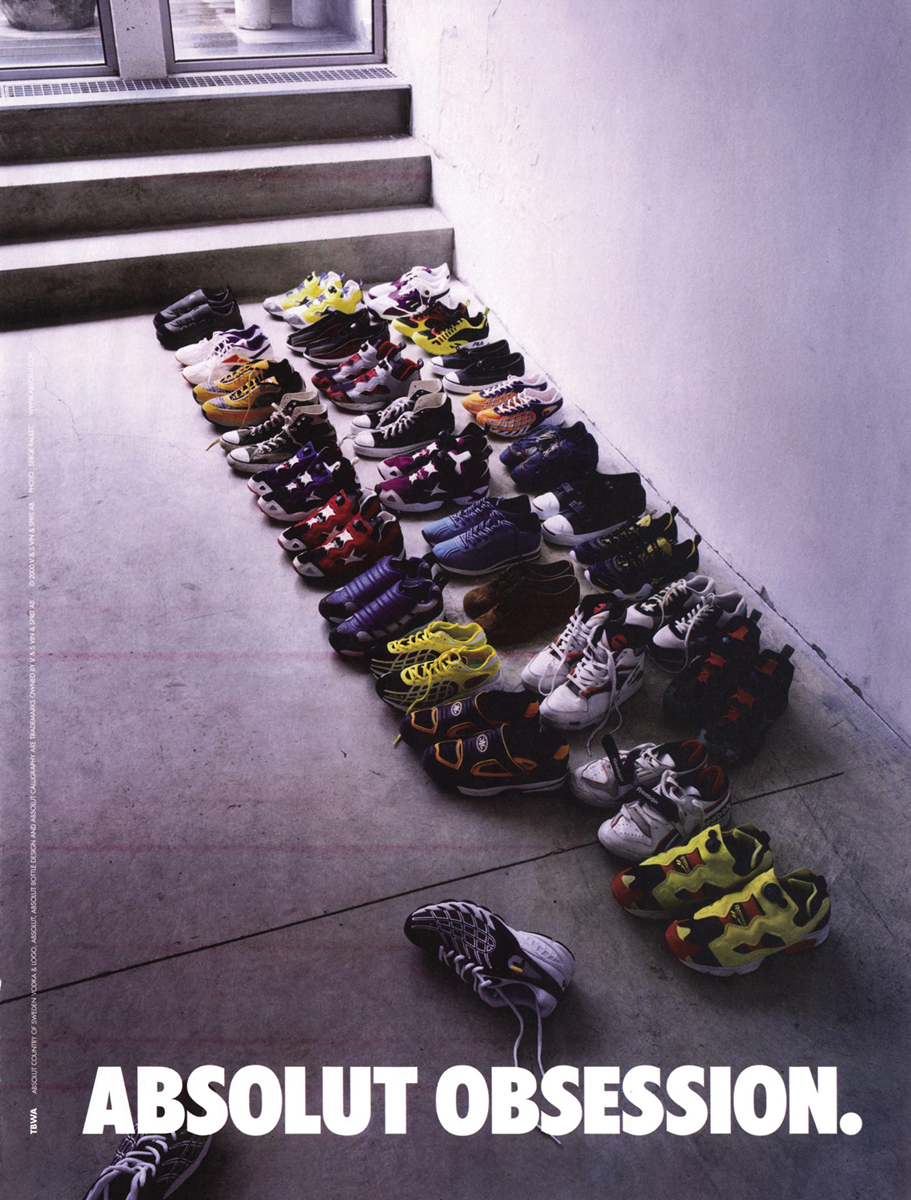

TBWA (now a unit of Omnicom) introduced Absolut Vodka’s distinctive advertising campaign in 1980. The campaign marketed a little-

Alcohol. In 2013, 88,000 people died from alcohol-

Alcohol ads have also targeted minority populations. Malt liquors, which contain higher concentrations of alcohol than beers do, have been touted in high-

College students, too, have been heavily targeted by alcohol ads, particularly by the beer industry. Although colleges and universities have outlawed “beer bashes” hosted and supplied directly by major brewers, both Coors and Miller still employ student representatives to help “create brand awareness.” These students notify brewers of special events that might be sponsored by and linked to a specific beer label. The images and slogans in alcohol ads often associate the products with power, romance, sexual prowess, or athletic skill. In reality, though, alcohol is a chemical depressant; it diminishes athletic ability and sexual performance, triggers addiction in roughly 10 percent of the U.S. population, and factors into many domestic abuse cases. A national study demonstrated “that young people who see more ads for alcoholic beverages tend to drink more.”35

Prescription Drugs. Another area of concern is the recent surge in prescription drug advertising. Spending on direct-

The tremendous growth of prescription drug ads brings the potential for false and misleading claims, particularly because a brief TV advertisement can’t possibly communicate all the relevant cautionary information. More recently, direct-

GLOBAL VILLAGE

Smoking Up the Global Market

By 2000, the status of tobacco companies and their advertising in the United States had hit a low point. A $206 billion settlement in 1998 between tobacco companies and state attorneys general ended tobacco advertising on billboards and severely limited the ways in which cigarette companies can promote their products in the United States. Advertising bans and antismoking public service announcements contributed to tobacco’s growing disfavor in America, with smoking rates dropping from a high of 42.5 percent of the population in 1965 to just 18 percent fifty years later.

As Western cultural attitudes have turned against tobacco, the large tobacco multinationals have shifted their global marketing focus, targeting Asia in particular. Of the world’s more than 1 billion smokers, 120 million adults smoke in India, 125 million adults smoke in Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam), and 350 million people smoke in China.1 Underfunded government health programs and populations that generally admire American and European cultural products make Asian nations ill-

© John van Hasselt/Sigma/Corbis

Advertising bans have actually forced tobacco companies to find alternative and, as it turns out, better ways to promote smoking. Philip Morris, the largest private tobacco company, and its global rival, British American Tobacco (BAT), practice “brand stretching”—linking their logos to race-

The unmistakable silhouette of the Marlboro Man is ubiquitous throughout developing countries, particularly in Asia. In Hanoi, Vietnam, almost every corner boasts a street vendor with a trolley cart, the bottom half of which carries the Marlboro logo or one of the other premium foreign brands. Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City has two thousand such trolleys. Children in Malaysia are especially keen on Marlboro clothing, which, along with watches, binoculars, radios, knives, and backpacks, they can win by collecting a certain number of empty Marlboro packages. (It is now illegal to sell tobacco-

Sporting events have proved to be an especially successful brand-

Critics suggest that the same marketing strategies will make their way into the United States and other Western countries, but that’s unlikely. Tobacco companies are mainly interested in developing regions like Asia for two reasons. First, the potential market is staggering: Only one in twenty cigarettes now sold in China is a foreign brand, and women are just beginning to develop the habit. Second, many smokers in countries like China are unaware that smoking causes lung cancer. In fact, a million Chinese people die each year from tobacco-

Watching Over Advertising

CELEBRITY SPOKESPEOPLE

Tennis champion Serena Williams recently endorsed the sleep supplement Sleep Sheets, an over-

A few nonprofit watchdog and advocacy organizations—

Excessive Commercialism

Since 1998, Commercial Alert, a nonprofit organization founded in part by longtime consumer advocate Ralph Nader and based in Portland, Oregon, has been working to “limit excessive commercialism in society” by informing the public about the ways that advertising has crept out of its “proper sphere.” For example, Commercial Alert highlights the numerous deals for cross-

These deals not only helped movie studios make money as DVD sales declined but also helped movies reach audiences that traditional advertising can’t. As Jeffrey Godsick, Fox’s executive VP of marketing, has said, “We want to hit all the lifestyle points for consumers. Partners get us into places that are nonpurchasable (as media buys). McDonald’s has access to tens of millions of people on a daily basis—

Commercial Alert is a lonely voice in checking the commercialization of U.S. culture. Its other activities have included challenges to specific marketing tactics, such as HarperCollins Children’s Books’ creation of the Mackenzie Blue series, which included “dynamic corporate partnerships,” or product placements woven into the stories, written by the founder of a marketing group aimed at teens. In constantly questioning the role of advertising in democracy, the organization has aimed to strengthen noncommercial culture and limit the amount of corporate influence on publicly elected government bodies.

The FTC Takes on Puffery and Deception

GREEN ADVERTISING

In response to increased consumer demand, companies have been developing and advertising green, or environmentally conscious, products to attract customers who want to lessen their environmental impact. How effective is this ad for you? What shared values do you look for or respond to in advertising? Rudi Von Briel/Photo Edit

Since the days when Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound promised “a sure cure for all female weakness,” false and misleading claims have haunted advertising. Over the years, the FTC, through its truth-

A typical example of deceptive advertising is the Campbell Soup ad in which marbles in the bottom of a soup bowl forced more bulky ingredients—

In 2003, the FTC brought enforcement actions against companies marketing the herbal weight-

When the FTC discovers deceptive ads, it usually requires advertisers to change them or remove them from circulation. The FTC can also impose monetary civil penalties for companies, and it occasionally requires an advertiser to run spots to correct the deceptive ads.

Alternative Voices

One of the provisions of the government’s multibillion-

Working with a coalition of ad agencies, a group of teenage consultants, and a $300 million budget, the foundation created a series of stylish, gritty print and television ads that deconstruct the images that have long been associated with cigarette ads—

The TV and print ads prominently reference the foundation’s Web site, www.thetruth.com, which offers statistics, discussion forums, and outlets for teen creativity. For example, the site provides facts about addiction (more than 80 percent of all adult smokers started smoking before they turned eighteen) and tobacco money (tobacco companies make $1.8 billion from underage sales) and urges site visitors to organize the facts in their own customized folders. By 2007, with its jarring messages and cross-

ALTERNATIVE ADS

In 2005, “Truth,” the national youth smoking prevention campaign, won an Emmy Award in the National Public Service Announcement category. “Truth” ads were created by the ad firms of Arnold Worldwide of Boston and Crispin Porter & Bogusky of Miami. Courtesy TRUTH/American Legacy Foundation