Early Developments in Public Relations

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the United States shifted to a consumer-

The first PR practitioners were simply theatrical press agents: those who sought to advance a client’s image through media exposure, primarily via stunts staged for newspapers. The advantages of these early PR techniques soon became obvious. For instance, press agents were used by people like Daniel Boone, who engineered various land-

Public Relations and Framing the Message The Advertising Archives (bottom left); © Bettmann/Corbis ( bottom center); The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY (top left); AP Photo/Longview News-

P. T. Barnum and Buffalo Bill

EARLY PUBLIC RELATIONS

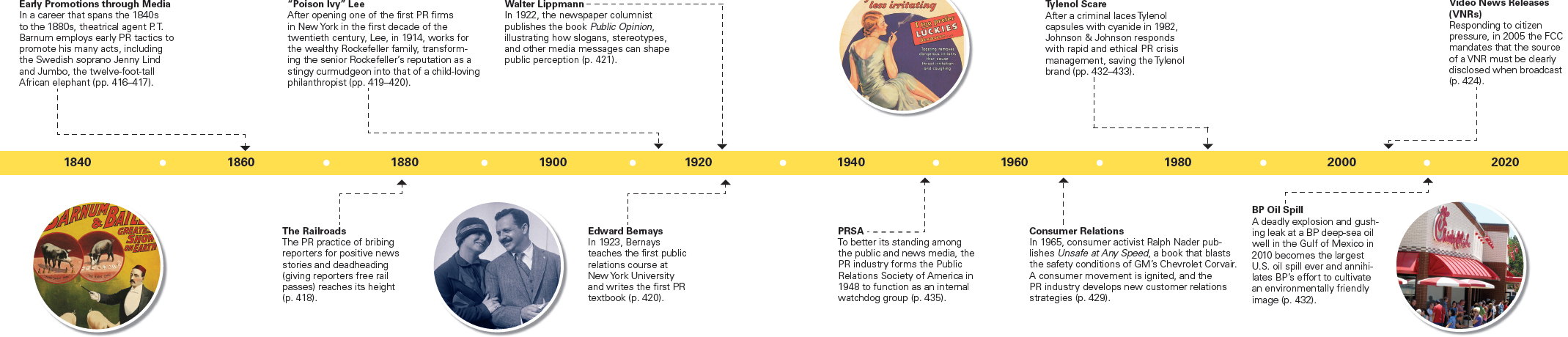

Originally called “P. T. Barnum’s Great Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome,” Barnum’s circus merged with Bailey’s circus in 1881 and again with the Ringling Bros. in 1919. Even with the ups and downs of the ringling bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus over the decades, Barnum’s original catchphrase, “The Greatest show on Earth,” endures to this day. The Advertising Archives

The most notorious press agent of the nineteenth century was Phineas Taylor (P. T.) Barnum, who used gross exaggeration, fraudulent stories, and staged events to secure newspaper coverage for his clients, his American Museum, and later his circus. Barnum’s circus, dubbed “The Greatest Show on Earth,” included the “midget” General Tom Thumb, Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, Jumbo the Elephant, and Joice Heth (who Barnum claimed was the 161-

From 1883 to 1916, William F. Cody, who once killed buffalo for the railroads, promoted himself and his traveling show: “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” Cody’s troupe—

Big Business and Press Agents

As P. T. Barnum, Buffalo Bill, and John Burke demonstrated, utilizing the press brought with it enormous power to sway the public and to generate business. So it is not surprising that during the nineteenth century, America’s largest industrial companies—

The railroads began to use press agents to help them obtain federal funds. Initially, local businesses raised funds to finance the spread of rail service. Around 1850, however, the railroads began pushing for federal subsidies, complaining that local fund-

The railroad press agents successfully gained government support by developing some of the earliest publicity tactics. Their first strategy was simply to buy favorable news stories about rail travel from newspapers through direct bribes. Another practice was to engage in deadheading—

Having obtained construction subsidies, the larger rail companies turned their attention to bigger game—

Along with the railroads, utility companies such as Chicago Edison and AT&T used PR strategies in the late nineteenth century to derail competition and eventually attain monopoly status. In fact, AT&T’s PR and lobbying efforts were so effective that they eliminated all telephone competition—

The Birth of Modern Public Relations

By the first decade of the twentieth century, reporters and muckraking journalists were investigating the promotional practices behind many companies. As an informed citizenry paid more attention, it became more difficult for large firms to fool the press and mislead the public. With the rise of the middle class, increasing literacy among the working classes, and the spread of information through print media, democratic ideals began to threaten the established order of business and politics—

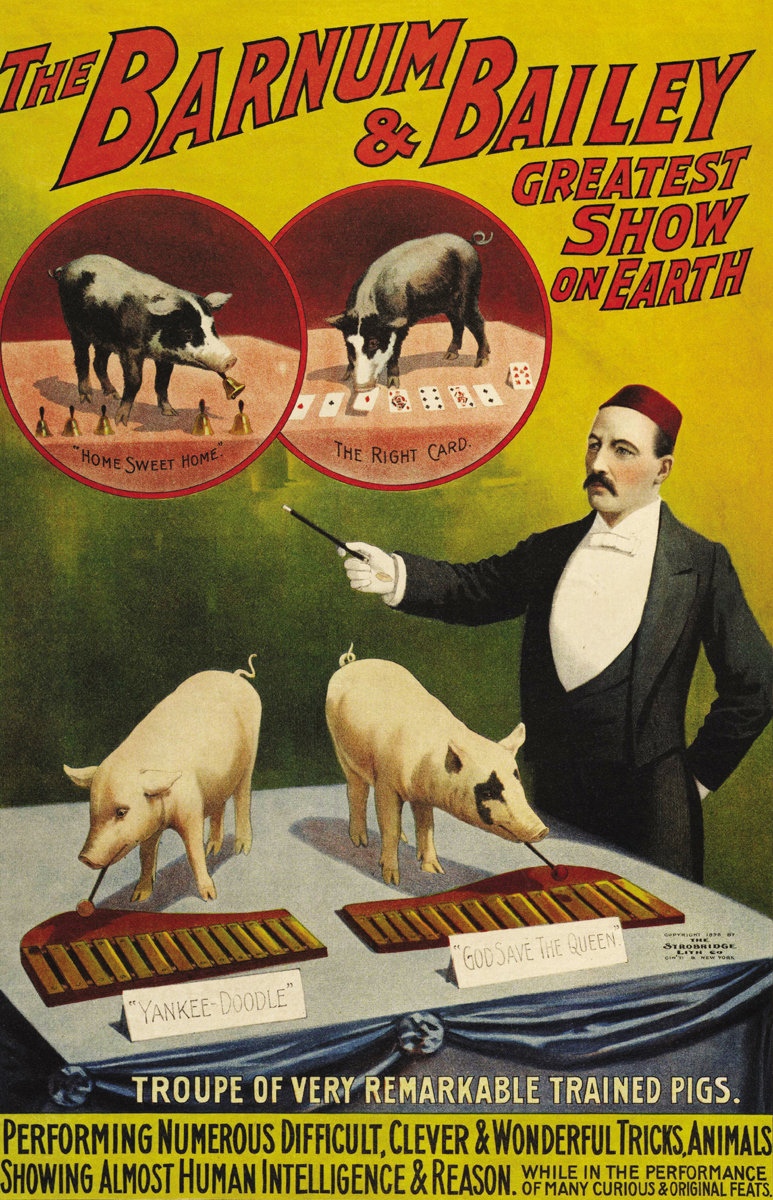

IVY LEE, a founding father of public relations (left), did more than just crisis work with large companies and business magnates. His PR work also included clients like transportation companies in New York City (right) and aviator Charles Lindbergh. © Bettmann/Corbis (left) Photo courtesy of Princeton University. Reprinted by permission (right).

Ivy Ledbetter Lee

Most nineteenth-

A minister’s son, an economics student at Princeton University, and a former reporter, Lee opened one of the first PR firms in the early 1900s with George Park. Lee quit the firm in 1906 to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which, following a rail accident, hired him to help downplay unfavorable publicity. Lee’s advice, however, was that Penn Railroad admit its mistake, vow to do better, and let newspapers in on the story. These suggestions ran counter to the then standard practice of hiring press agents to manipulate the media, yet Lee argued that an open relationship between business and the press would lead to a more favorable public image. In the end, Penn and subsequent clients, notably John D. Rockefeller, adopted Lee’s successful strategies.

By the 1880s, Rockefeller controlled 90 percent of the nation’s oil industry and suffered from periodic image problems, particularly after Ida Tarbell’s powerful muckraking series about the ruthless business tactics practiced by Rockefeller and his Standard Oil Company appeared in McClure’s Magazine in 1904. The Rockefeller and Standard Oil reputations reached a low point in April 1914, when tactics to stop union organizing erupted in tragedy at a coal company in Ludlow, Colorado. During a violent strike, fifty-

Lee was hired to contain the damaging publicity fallout. He immediately distributed a series of “fact” sheets to the press, telling the corporate side of the story and discrediting the tactics of the United Mine Workers, who had organized the strike. As he had done for Penn Railroad, Lee also brought in the press and staged photo opportunities. John D. Rockefeller Jr., who now ran the company, donned overalls and a miner’s helmet and posed with the families of workers and union leaders. This was probably the first use of a PR campaign in a labor-

Called “Poison Ivy” by corporate foes and critics within the press, Lee had a complex understanding of facts. For Lee, facts were elusive and malleable, begging to be forged and shaped. “Since crowds do not reason,” he noted in 1917, “they can only be organized and stimulated through symbols and phrases.”11 In the Ludlow case, for instance, Lee noted that the women and children who died while retreating from the charging company-

Edward Bernays

The nephew of Sigmund Freud, former reporter Edward Bernays inherited the public relations mantle from Ivy Lee. Beginning in 1919, when he opened his own office, Bernays was the first person to apply the findings of psychology and sociology to public relations, referring to himself as a “public relations counselor” rather than a “publicity agent.” Over the years, Bernays’s client list included General Electric, the American Tobacco Company, General Motors, Good Housekeeping and Time magazines, Procter & Gamble, RCA, the government of India, the city of Vienna, and President Coolidge.

Bernays also worked for the Committee on Public Information (CPI) during World War I, developing propaganda that supported America’s entry into that conflict and promoting the image of President Woodrow Wilson as a peacemaker. Both efforts were among the first full-

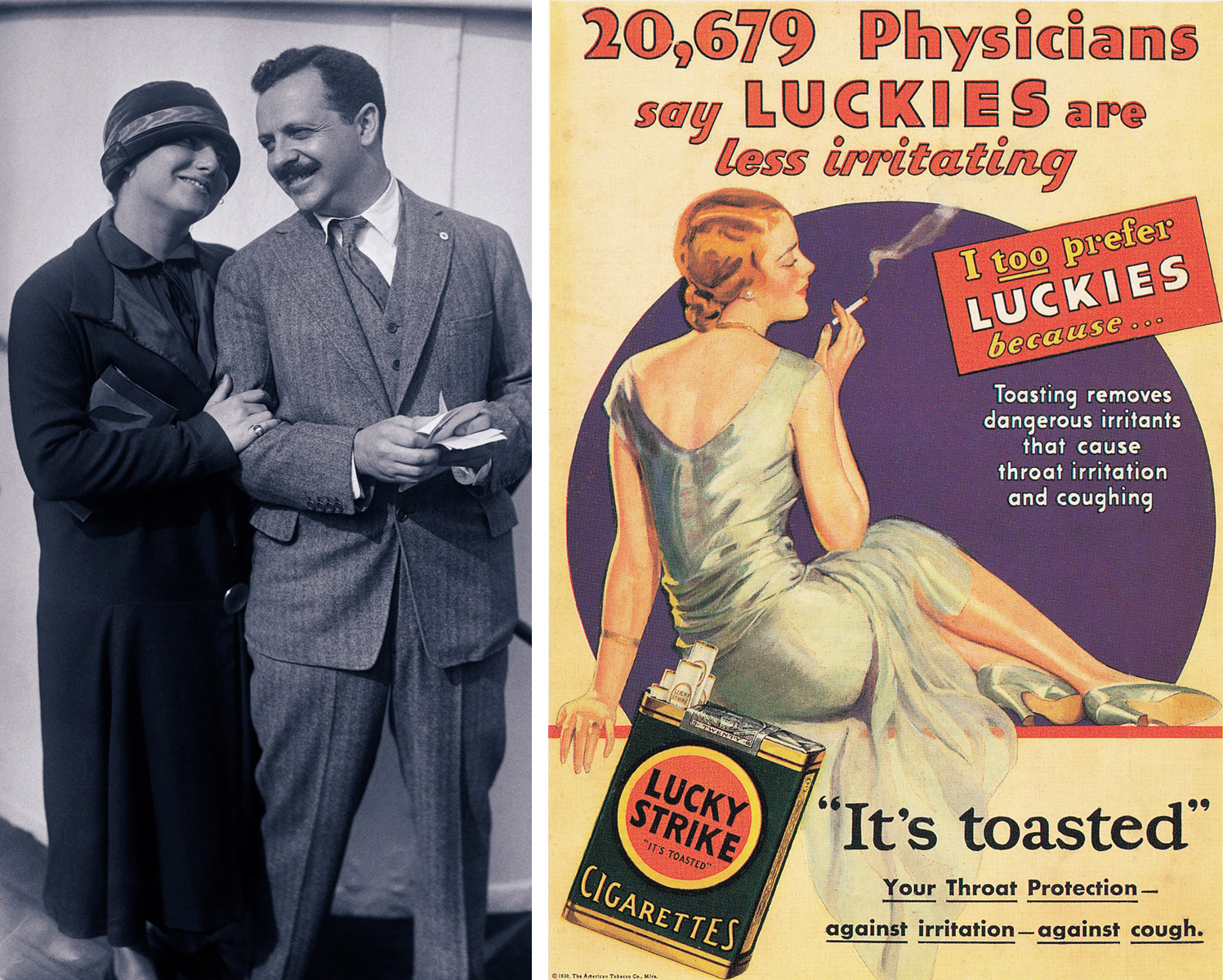

In the 1920s, Bernays was hired by the American Tobacco Company to develop a campaign to make smoking more publicly acceptable for women (similar campaigns are under way today in countries like China). Among other strategies, Bernays staged an event: placing women smokers in New York’s 1929 Easter parade. He labeled cigarettes “torches of freedom” and encouraged women to smoke as a symbol of their newly acquired suffrage and independence from men. He also asked the women he placed in the parade to contact newspaper and newsreel companies in advance—

Through much of his writing, Bernays suggested that emerging freedoms threatened the established hierarchical order. He thought it was important for experts and leaders to control the direction of American society: “The duty of the higher strata of society—

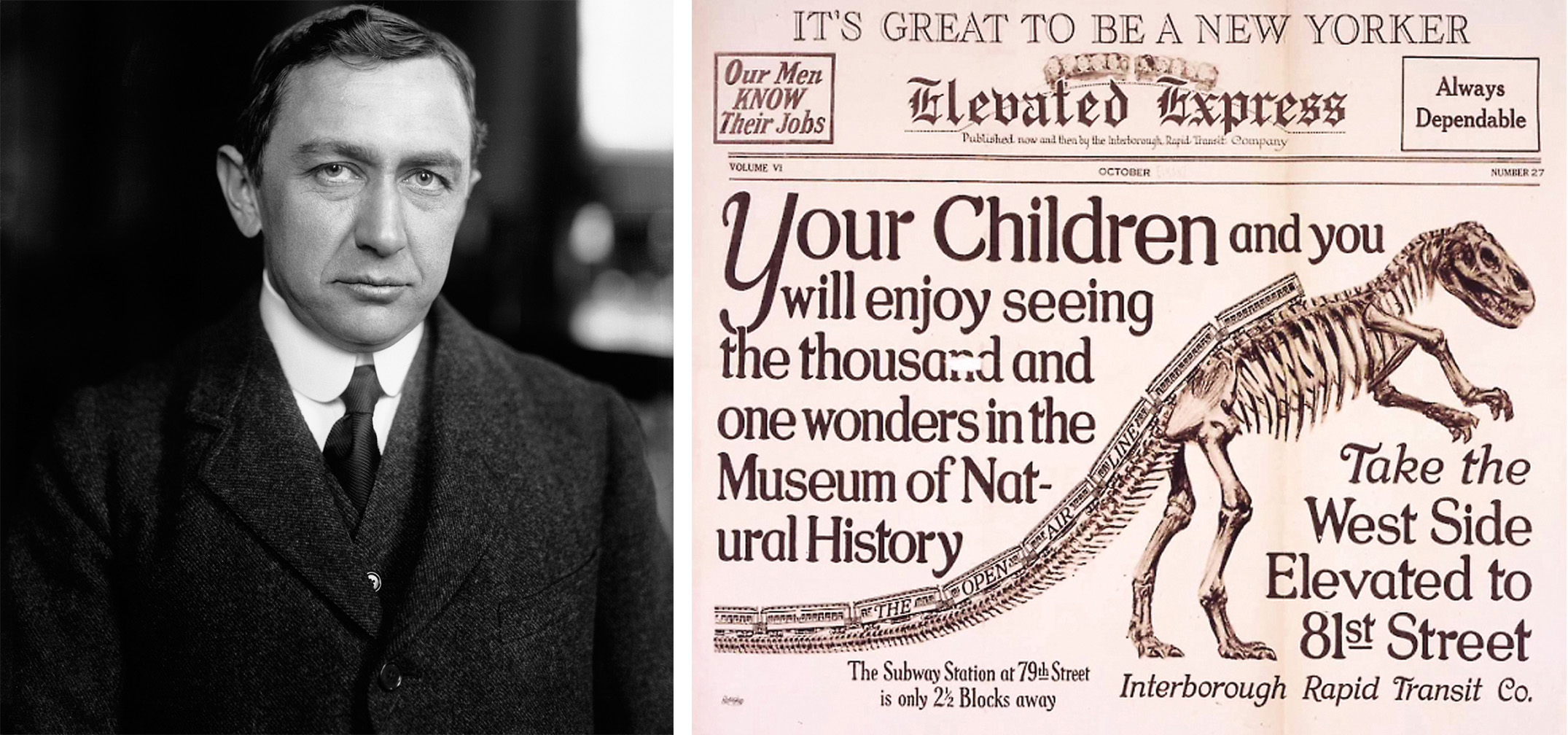

EDWARD BERNAYS with his business partner and wife, Doris Fleischman (left ). Bernays worked on behalf of a client, the American Tobacco Company, to make smoking socially acceptable for women. For one of American Tobacco’s brands, Lucky Strike, they were also asked to change public attitudes toward the color green. (Women weren’t buying the brand because surveys indicated that the forest green package clashed with their wardrobes.) Bernays and Fleischman organized events such as green fashion shows and sold the idea of a new trend in green to the press. By 1934, green had become the fashion color of the season, making Lucky Strike cigarettes the perfect accessory for the female smoker. Interestingly, Bernays forbade his own wife to smoke, flushing her cigarettes down the toilet and calling smoking a nasty habit. © Bettmann/Corbis (left) The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY (right)

Throughout Bernays’s most active years, his business partner and later his wife, Doris Fleischman, worked with him on many of his campaigns as a researcher and coauthor. Beginning in the 1920s, she was one of the first women to work in public relations, and she introduced PR to America’s most powerful leaders through a pamphlet she edited called Contact. Because she opened up the profession to women from its inception, PR emerged as one of the few professions—