Tensions between Public Relations and the Press

In 1932, Stanley Walker, an editor at the New York Herald Tribune, identified public relations agents as “mass-

Much of this antagonism, directed at public relations from the journalism profession, is historical. Journalists have long considered themselves part of a public service profession, but some regard PR as having emerged as a pseudo-

Elements of Professional Friction

The relationship between journalism and PR is important and complex. Although journalism lays claim to independent traditions, the news media have become ever more reliant on public relations because of the increasing amount of information now available. Newspaper staff cutbacks, combined with television’s need for local news events, have expanded the news media’s need for PR story ideas.

Another cause of tension is that PR firms often raid the ranks of reporting for new talent. Because most press releases are written to imitate news reports, the PR profession has always sought good writers who are well connected to sources and savvy about the news business. For instance, the fashion industry likes to hire former style or fashion news writers for its PR staff, and university information offices seek reporters who once covered higher education. However, although reporters frequently move into PR, public relations practitioners seldom move into journalism; the news profession rarely accepts prodigal sons or daughters back into the fold once they have left reporting for public relations. Nevertheless, the professions remain codependent: PR needs journalists for publicity, and journalism needs PR for story ideas and access.

Public relations, by making reporters’ jobs easier, has often enabled reporters to become lazy. PR firms now supply what reporters used to gather for themselves. Instead of trying to get a scoop, many journalists are content to wait for a PR handout or a good tip before following up on a story. Some members of the news media, grateful for the reduced workload that occurs when they are provided with handouts, may be hesitant to criticize a particular PR firm’s clients. Several issues shed light on this discord and on the ways in which different media professions interact.

Undermining Facts and Blocking Access

Journalism’s most prevalent criticism of public relations is that it works to counter the truths reporters seek to bring to the public. Modern public relations redefined and complicated the notion of what “facts” are. PR professionals demonstrated that the facts can be spun in a variety of ways, depending on what information is emphasized and what is downplayed. As Ivy Lee noted in 1925: “The effort to state an absolute fact is simply an attempt to achieve what is humanly impossible; all I can do is to give you my interpretation of the facts.”24 With practitioners like Lee showing the emerging PR profession how the truth could be interpreted, the journalist’s role as a custodian of accurate information became much more difficult.

Journalists have also objected that PR professionals block press access to key business leaders, political figures, and other newsworthy people. Before the prevalence of PR, reporters could talk to such leaders directly and obtain quotable information for their news stories. Now, however, journalists complain that PR agents insert themselves between the press and the newsworthy, thus disrupting the journalistic tradition in which reporters would vie for interviews with top government and business leaders. Journalists further argue that PR agents are now able to manipulate reporters by giving exclusives to journalists who are likely to cast a story in a favorable light or by cutting off a reporter’s access to one of their newsworthy clients altogether if that reporter has written unfavorably about the client in the past.

Promoting Publicity and Business as News

Another explanation for the professional friction between the press and PR involves simple economics. As Michael Schudson noted in his book Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers, PR agents help companies “promote as news what otherwise would have been purchased in advertising.”25 Accordingly, Ivy Lee wrote to John D. Rockefeller after he gave money to Johns Hopkins University: “In view of the fact that this was not really news, and that the newspapers gave so much attention to it, it would seem that this was wholly due to the manner in which the material was ‘dressed up’ for newspaper consumption. It seems to suggest very considerable possibilities along this line.”26 News critics worry that this type of PR is taking media space and time away from those who do not have the financial resources or the sophistication to become visible in the public eye. There is another issue: If public relations can secure news publicity for clients, the added credibility of a journalistic context gives clients a status that the purchase of advertising cannot offer.

Another criticism is that PR firms with abundant resources clearly get more client coverage from the news media than their lesser-

Shaping the Image of Public Relations

Dealing with both a tainted past and journalism’s hostility has often preoccupied the public relations profession, leading to the development of several image-

| PRSA Member Statement of Professional Values |

| This statement presents the core values of PRSA members and, more broadly, of the public relations profession. These values provide the foundation for the Member Code of Ethics and set the industry standard for the professional practice of public relations. These values are the fundamental beliefs that guide our behaviors and decision- |

| ADVOCACY We serve the public interest by acting as responsible advocates for those we represent.We provide a voice in the marketplace of ideas, facts, and viewpoints to aid informed public debate. |

| HONESTY We adhere to the highest standards of accuracy and truth in advancing the interests of those we represent and in communicating with the public. |

| EXPERTISE We acquire and responsibly use specialized knowledge and experience. We advance the profession through continued professional development, research, and education. We build mutual understanding, credibility, and relationships among a wide array of institutions and audiences. |

| INDEPENDENCE We provide objective counsel to those we represent. We are accountable for our actions. |

| LOYALTY We are faithful to those we represent, while honoring our obligation to serve the public interest. |

| FAIRNESS We deal fairly with clients, employers, competitors, peers, vendors, the media, and the general public. We respect all opinions and support the right of free expression. |

Table 12.2: TABLE 12.2 PUBLIC RELATIONS SOCIETY OF AMERICA ETHICS CODE In 2000, the PRSA approved a completely revised Code of Ethics, which included core principles, guidelines, and examples of improper conduct. Here is one section of the code. Data from: The full text of the PRSA Code of Ethics is available at www.prsa.org.

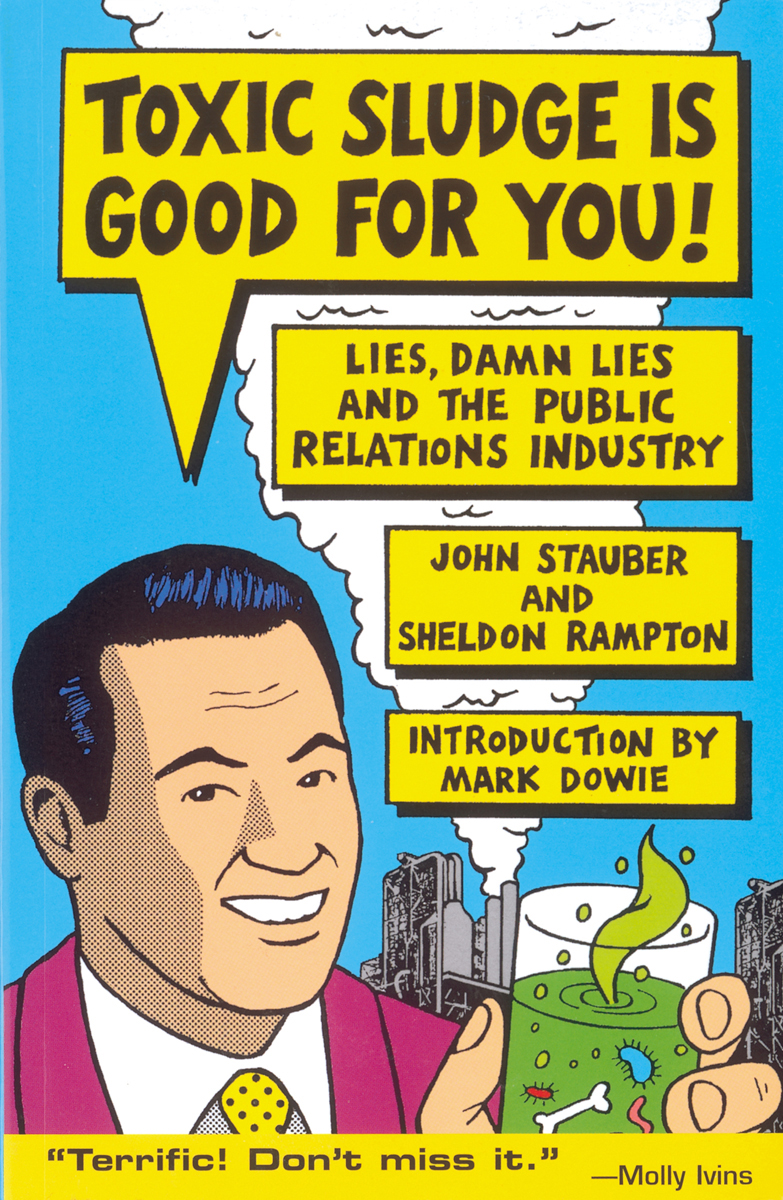

THE INVISIBILITY OF PUBLIC RELATIONS is addressed in a series of books by John Stauber and Sheldon Rampton. Courtesy of Common Courage Press. Reprinted by permission.

Over the years, as PR has subdivided itself into specialized areas, it has used more positive phrases, such as institutional relations, corporate communications, and news and information services to describe what it does. Public relations’ best press strategy, however, may be the limitations of the journalism profession itself. For most of the twentieth century, many reporters and editors clung to the ideal that journalism is, at its best, an objective institution that gathers information on behalf of the public. Reporters have only occasionally turned their pens, computers, and cameras on themselves to examine their own practices or their vulnerability to manipulation. Thus by not challenging PR’s more subtle strategies, many journalists have allowed PR professionals to interpret “facts” to their clients’ advantage.

Alternative Voices

Because public relations professionals work so closely with the press, their practices are not often the subject of media reports or investigations. Indeed, the multibillion-

CMD staff members have also written books targeting public relations practices having to do with the Republican Party’s lobbying establishment (Banana Republicans), U.S. propaganda on the Iraq War (The Best War Ever), industrial waste (Toxic Sludge Is Good for You! ), mad cow disease (Mad Cow USA), and PR uses of scientific research (Trust Us, We’re Experts!). Their work helps bring an alternative angle to the well-