Specialization, Global Markets, and Convergence

In today’s complex and often turbulent economic environment, global firms have sought greater profits by moving labor to less economically developed countries that need jobs but have poor health and safety regulations for workers. The continuous outsourcing of many U.S. jobs and the breakdown of global economic borders accompanied this transformation. Bolstered by the passage of GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) in 1947, the signing of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) in 1994, and the formation of the WTO (World Trade Organization, which succeeded GATT in 1995), global cooperation fostered transnational media corporations and business deals across international terrain.

But in many cases, this global expansion by U.S. companies ran counter to America’s early-

The Rise of Specialization and Synergy

The new globalism coincided with the rise of specialization. The magazine, radio, and cable industries sought specialized markets both in the United States and overseas, in part to counter television’s mass appeal. By the 1980s, however, even television—

Beyond specialization, though, what really distinguishes current media economics is the extension of synergy to international levels. Synergy typically refers to the promotion and sale of different versions of a media product across the various subsidiaries of a media conglomerate (e.g., a Weather Channel segment on NBC’s Today Show, or an NBC News reporter appearing on MSNBC for election coverage—

Disney: A Postmodern Media Conglomerate

The Walt Disney Company is one of the most successful companies in leveraging its many properties to create synergies. For example, in 2014, ABC broadcast the prime-

The Early Years

After Walt Disney’s first cartoon company, Laugh-

For much of the twentieth century, the Disney company set the standard for popular cartoons and children’s culture. The Silly Symphonies series (1929–

Around the time of the demise of the cartoon film short in movie theaters, Disney expanded into other areas, with its first nature documentary short, Seal Island (1949); its first live-

Disney was also among the first film studios to embrace television, launching a long-

In 1953, Disney started Buena Vista, a distribution company. This was the first step in making the studio into a major player. The company also began exploiting the power of its early cartoon features. Snow White, for example, was successfully rereleased in theaters to new generations of children before eventually going to videocassette and much later to DVD.

Global Expansion

The death of Walt Disney in 1966 triggered a period of decline for the studio. But in 1984, a new management team, led by Michael Eisner, initiated a turnaround. The newly created Touchstone movie division reinvented the live-

Disney also came to epitomize the synergistic possibilities of media consolidation. It can produce an animated feature for both theatrical release and DVD distribution. With its ABC network (purchased in 1995), it can promote Disney movies and television shows on programs like Good Morning America. A book version can be released through Disney’s publishing arm, Disney Publishing Worldwide, and “the-

FOR ABOUT A DECADE, DISNEY ANIMATION WAS DEFINED more by Pixar, the computer-

Throughout the 1990s, Disney continued to find new sources of revenue in both entertainment and distribution. Through its purchase of ABC, Disney also became the owner of the cable sports channels ESPN and ESPN2, and later expanded the brand with ESPNEWS, ESPN Classic, and ESPNU channels; ESPN The Magazine; ESPN Radio; and ESPN.go.com. In New York City, Disney renovated several theaters and launched versions of Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King, and Spider-

Building on the international appeal of its cartoon features, Disney extended its global reach by opening Tokyo Disney Resort in 1983 and Disneyland Paris in 1991. On the home front, a proposed historical park in Virginia—

Despite criticism, little slowed Disney’s global expansion. Orbit—

Disney Today

Even as Disney grew into the world’s No. 2 media conglomerate by the beginning of the twenty-

The Pixar deal showed that Disney was ready to embrace the digital age. In an effort to focus on television, movies, and its online initiatives, Disney sold its twenty-

CASE STUDY

Minority and Female Media Ownership: Why It Matters

The giant merger in 2010 between “Big Network” (NBC) and “Big Cable” (Comcast) signaled a key economic strategy for traditional media industries in the age of the Internet. By claiming that “Big Internet” companies like Google and Amazon (especially as they move into content development) pose enough of a threat to old media, traditional media companies pushed for the dissolution of remaining ownership restrictions. However, the big NBC-

Back in the 1970s, the FCC enacted rules that prohibited a single company from owning more than seven AM radio stations, seven FM radio stations, and seven TV stations (called “the 7-

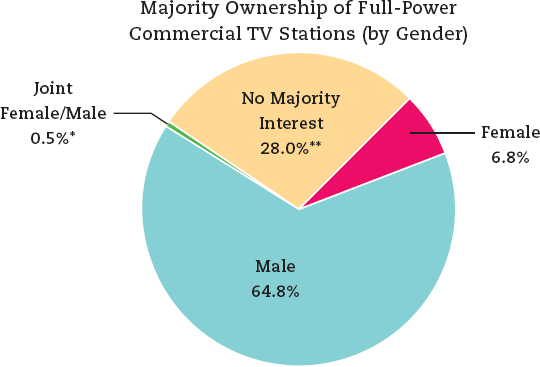

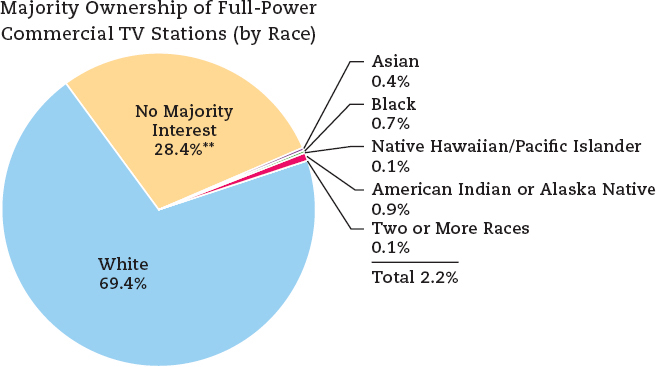

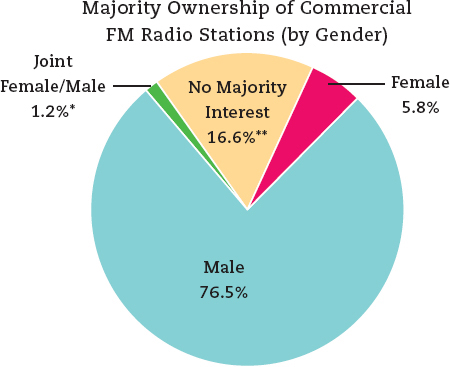

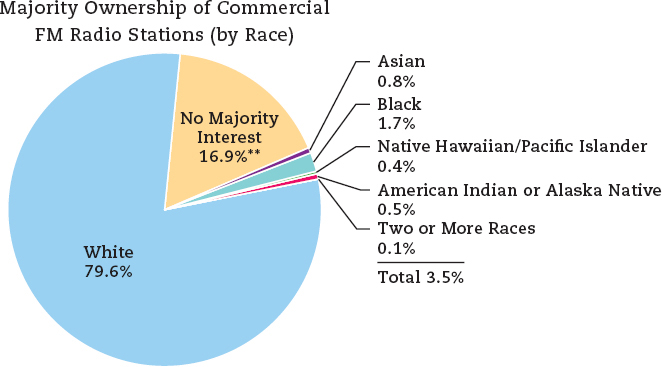

In the United States, where women constitute slightly more than 50 percent of the population, blacks are about 13 percent of the population, and Hispanics are more than 16 percent of the population, television and radio broadcasting ownership diversity is poor by any measure.

The Free Press, in its formal response to the FCC’s 2012 report on ownership, argued that “the level of female and minority ownership in the broadcast marketplace is disproportionately and embarrassingly low,” with “a nearly 20 percent decline in the level of minority ownership since 2006.”2 (In 2014, FCC chairman Tom Wheeler acknowledged that African American ownership of television stations in the United States had dropped from nineteen in 2006 to just four in 2014. Moreover, in three of those four cases, the black station owners had a joint sales agreement with a larger media corporation, requiring them to turn over up to 90 percent of their profits to the corporate partner.)3 The group criticized the FCC for not taking its obligations to serve the public interest seriously and for not fully studying the impact that relaxed ownership rules have on minority and female broadcast station ownership. (In its own calculations, the Free Press found even lower levels of diversity in station ownership than the FCC did.) It contended that large chains have enormous power in the marketplace and ultimately harm minority and female ownership:

As markets become more concentrated, artificial economies of scale are created. This drives away potential new entrants in favor of existing large chains. Concentration also has the effect of diminishing the ability of existing smaller station groups and single-

The only means at the FCC’s disposal to prevent further erosion of diversity in media are limitations on station ownership, according to the United States Court of Appeals, which ruled in 2011 that the “Commission had failed to consider the effect on minority ownership of the repeal” of ownership restrictions.5

The point of diversity in ownership is to increase the variety of voices in the public sphere, which the FCC is required to do as part of its mission in the public interest. Yet there is continuing pressure applied to the FCC and Congress by large media conglomerates that want to grow even larger; thus, battle over ownership deregulation continues to be an issue worthy of close public attention.

All chart data from: Federal Communications Commission, “Report on Ownership of Commercial Broadcast Stations,” DA 12-

*“Joint female/male” cases are those in which a female and a male each control a 50 percent interest in the station.

**“No majority interest” cases are those in which no party owns 50 percent (a majority) or more controlling interest in a station.

Global Audiences Expand Media Markets

As Disney’s story shows, international expansion has allowed media conglomerates some advantages, including secondary markets in which to earn profits and advance technological innovations. First, as media technologies get cheaper and more portable (think Walkman to iPod), American media proliferate both inside and outside national boundaries. Today, greatly facilitated by the Internet, media products easily reach the eyes and ears of the world. Second, this globalism permits companies that lose money on products at home to profit abroad. Roughly 80 percent of U.S. movies, for instance, do not earn back their costs in U.S. theaters and depend on foreign circulation and video revenue to make up for losses.

In addition, satellite transmission has made North American and European TV available at the global level. Cable services such as CNN and MTV quickly took their national acts to the international stage, and by the twenty-

The Internet and Convergence Change the Game

HBO GO

Acclaimed HBO original programming, including Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and a variety of other TV series and movies, is available online through the company’s HBO Go online service—

For much of their history, media companies have been part of usually discrete or separate industries—

The Rise of the New Digital Media Conglomerates

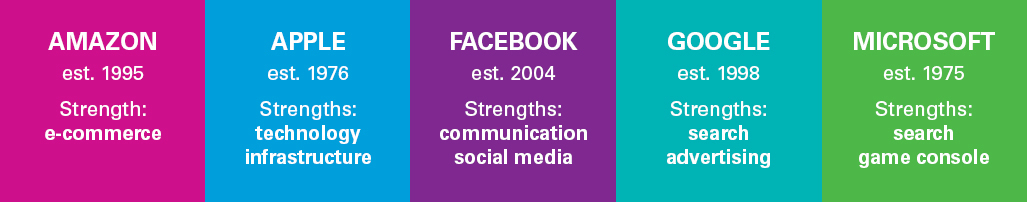

The digital turn marks a shift in the media environment, from the legacy media powerhouses like Time Warner and Disney to the new digital media conglomerates. Five companies—

FIGURE 13.3 RISE OF THE NEW DIGITAL MEDIA CONGLOMERATES

Each of the five leading companies has become powerful for different reasons. Amazon’s entrée is that it has grown into the largest e-

Facebook’s strength has been its ability to become central to communication and social media. As Facebook’s number of users surpassed one billion worldwide in 2012, the company still struggled to fully leverage those users (and the massive amounts of data they share about themselves) into advertising sales, particularly as its users moved to accessing Facebook via mobile phones. Unlike the other four digital companies, Facebook lacks hardware devices to access the Internet and digital media, although it began to remedy that problem with the purchase of the Oculus Rift virtual reality gaming headset for $2 billion in 2014. Google, which draws its huge numbers of users through its search function, has much more successfully translated those users (and the information provided by their search terms) into an advertising business worth more than $59 billion a year. Google is also moving into the same digital media distribution business that Apple and Amazon offer, via its Android phone operating system, Nexus 7 tablet, Chromebook, and Chromecast. Microsoft, one of the wealthiest digital companies in the world, is making the transition from being the top software company (a business that is slowly in decline) to competing in the digital media world with its Bing search engine and devices like its successful Xbox game console, Surface tablet, and Windows phone. Microsoft also owns Yammer, a business social network, and holds a small ownership share in Facebook.

Given how technologically adept these five digital corporations have proven to be, they still need to provide compelling narratives to attract people (to repeat a point from the beginning of the chapter). All five companies are weak in this regard, as they rely on other companies’ media narratives (e.g., the sounds, images, words, and pictures) or the stories that their own users provide (as in Facebook posts or YouTube videos). Amazon is leading the other companies in content development, though, with its own publishing divisions (to compete with publishing companies) and its own original television series and online channels like Twitch (to compete with Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube. It’s likely that the other digital companies will eventually do the same. The history of mass communication suggests that it is the content—

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Cultural Imperialism and Movies

In the 1920s, the U.S. film industry became the leader in the worldwide film business. The images and stories of American films are well known in nearly every corner of the world. But with major film production centers in places like India, China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Russia, and Nigeria, to what extent do U.S. films dominate international markets today? Conversely, how often do international films get much attention in the United States?

1 DESCRIPTION. Using international box-

2 ANALYSIS. What patterns emerged in each country’s box-

3 INTERPRETATION. So what do your discoveries mean? Can you make an argument for or against the existence of cultural imperialism by the United States? Are there film industries in other countries that dominate movie theaters in their region of the world? How would you critique the reverse of cultural imperialism, wherein films from other countries rarely break into the Top 10 box-

4 EVALUATION. Given your interpretation, is cultural dominance by one country a good thing or a bad thing? Consider the potential advantages of creating a global village of shared popular culture versus the potential disadvantages of cultural imperialism. Also, is there any potential harm in a country’s Top 10 box-

5 ENGAGEMENT. Contact managers of your local movie theater (or executives at the headquarters of the chain that owns it). Ask them how they decide which films to screen. If they don’t show many international films, ask them why not. Be ready to provide a list of three to five international films released in the United States (see the full list of current U.S. releases at www.boxofficemojo.com) that haven’t yet been screened in the theater.

The Digital Age Favors Small, Flexible Start-

All the leading digital companies of today were once small start-

Today, the juncture in the digital era is the growing importance of social media and mobile devices. Like in the earlier periods, the strategy for start-