Research on Media Effects

As concern about public opinion, propaganda, and the impact of the media merged with the growth of journalism and mass communication departments in colleges and universities, media researchers looked more and more to behavioral science as the basis of their research. Between 1930 and 1970, as media historian Daniel Czitrom has noted, “Who says what to whom with what effect?” became the key question “defining the scope and problems of American communications research.”11 In addressing this question specifically, media effects researchers asked follow-

Early Theories of Media Effects

A major goal of scientific research is to develop theories or laws that can consistently explain or predict human behavior. The varied impacts of the mass media and the diverse ways in which people make popular culture, however, tend to defy predictable rules. Historical, economic, and political factors influence media industries, making it difficult to develop systematic theories that explain communication. Researchers developed a number of small theories, or models, that help explain individual behavior rather than the impact of the media on large populations. But before these small theories began to emerge in the 1970s, mass media research followed several other models. Developing between the 1930s and the 1970s, these major approaches included the hypodermic-

The Hypodermic-

One of the earliest media theories attributed powerful effects to the mass media. A number of intellectuals and academics were fearful of the influence and popularity of film and radio in the 1920s and 1930s. Some social psychologists and sociologists who arrived in the United States after fleeing Germany and Nazism in the 1930s had watched Hitler use radio, film, and print media as propaganda tools. They worried that the popular media in America also had a strong hold over vulnerable audiences. The concept that powerful media affect weak audiences has been labeled the hypodermic-

MEDIA EFFECTS?

In The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic, Hadley Cantril (1906–

One of the earliest challenges to this theory involved a study of Orson Welles’s legendary October 30, 1938, radio broadcast of War of the Worlds, which presented H. G. Wells’s Martian invasion novel in the form of a news report and frightened millions of listeners who didn’t realize it was fictional (see Chapter 5). In a 1940 book-

The Minimal-

Cantril’s research helped lay the groundwork for the minimal-

For some children, under some conditions, some television is harmful. For other children under the same conditions, or for the same children under other conditions, it may be beneficial. For most children, under most conditions, most television is probably neither particularly harmful nor particularly beneficial.12

In addition, Joseph Klapper’s important 1960 research study, The Effects of Mass Communication, found that the mass media only influenced individuals who did not already hold strong views on an issue and that the media had a greater impact on poor and uneducated audiences. Solidifying the minimal-

The minimal-

In a sense the term “effect” is misleading because it suggests that television “does something” to children. The connotation is that television is the actor, the children are acted upon. Children are thus made to seem relatively inert; television, relatively active. Children are sitting victims; television bites them. Nothing can be further from the fact. It is the children who are most active in this relationship. It is they who use television, rather than television that uses them.14

Indeed, as the authors observed, numerous studies have concluded that viewers—

The Uses and Gratifications Model

USES AND GRATIFICATIONS

In 1952, audience members at the Paramount Theater in Hollywood donned 3-

A response to the minimal-

Although the uses and gratifications model addressed the functions of the mass media for individuals, it did not address important questions related to the impact of the media on society. Once researchers had accumulated substantial inventories of the uses and functions of media, they often did not move in new directions. Consequently, uses and gratifications never became a dominant or an enduring theory in media research.

Conducting Media Effects Research

Media research generally comes from the private or public sector, and each type has distinguishing features. Private research, sometimes called proprietary research, is generally conducted for a business, a corporation, or even a political campaign. It is usually applied research in the sense that the information it uncovers typically addresses some real-

Most media research today focuses on the effects of the media in such areas as learning, attitudes, aggression, and voting habits. This research employs the scientific method, a blueprint long used by scientists and scholars to study phenomena in systematic stages. The steps in the scientific method include the following:

- Identifying the research problem

- Reviewing existing research and theories related to the problem

- Developing working hypotheses or predictions about what the study might find

- Determining an appropriate method or research design

- Collecting information or relevant data

- Analyzing results to see if the hypotheses have been verified

- Interpreting the implications of the study to determine whether they explain or predict the problem

The scientific method relies on objectivity (eliminating bias and judgments on the part of researchers); reliability (getting the same answers or outcomes from a study or measure during repeated testing); and validity (demonstrating that a study actually measures what it claims to measure).

In scientific studies, researchers pose one or more hypotheses: tentative general statements that predict the influence of an independent variable on a dependent variable. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that frequent TV viewing among adolescents (independent variable) causes poor academic performance (dependent variable). Or another researcher might hypothesize that playing first-

Broadly speaking, the methods for studying media effects on audiences have taken two forms—

Experiments

Like all studies that use the scientific method, experiments in media research isolate some aspect of content; suggest a hypothesis; and manipulate variables to discover a particular medium’s impact on attitude, emotion, or behavior. To test whether a hypothesis is true, researchers expose an experimental group—the group under study—

For instance, to test the effects of violent films on preadolescent boys, a research study might take a group of ten-

When experiments carefully account for independent variables through random assignment, they generally work well to substantiate direct cause-

Experiments have other limitations as well. First, they are not generalizable to a larger population; they cannot tell us whether cause-

Survey Research

In the simplest terms, survey research is the collecting and measuring of data taken from a group of respondents. Using random sampling techniques that give each potential subject an equal chance to be included in the survey, this research method draws on much larger populations than those used in experimental studies. Surveys may be conducted through direct mail, personal interviews, telephone calls, e-

Two other benefits of surveys are that they are usually generalizable to the larger society and that they enable researchers to investigate populations in long-

Like experiments, surveys have several drawbacks. First, survey investigators cannot account for all the variables that might affect media use; therefore, they cannot show cause-

Content Analysis

Over the years, researchers recognized that experiments and surveys focused on general topics (violence) while ignoring the effects of specific media messages (gun violence, fistfights). As a corrective, researchers developed a method known as content analysis to study these messages. Such analysis is a systematic method of coding and measuring media content.

Although content analysis was first used during World War II for radio, more recent studies have focused on television, film, and the Internet. Probably the most influential content analysis studies were conducted by George Gerbner and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania. Beginning in the late 1960s, they coded and counted acts of violence on network television. Combined with surveys, their annual “violence profiles” showed that heavy watchers of television, ranging from children to retired Americans, tend to overestimate the amount of violence that exists in the actual world.17

The limits of content analysis, however, have been well documented. First, this technique does not measure the effects of the messages on audiences, nor does it explain how those messages are presented. For example, a content analysis sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation that examined more than eleven hundred television shows found that 70 percent featured sexual content.18 But the study didn’t explain how viewers interpreted the content or the context of the messages.

Second, problems of definition occur in content analysis. For instance, in the case of coding and counting acts of violence, how do researchers distinguish slapstick cartoon aggression from the violent murders or rapes in an evening police drama? Critics point out that such varied depictions may have diverse and subtle effects on viewers that are not differentiated by content analysis. Third, critics point out that as content analysis grew to be a primary tool in media research, it sometimes pushed to the sidelines other ways of thinking about television and media content. Broad questions concerning the media as a popular art form, as a measure of culture, as a democratic influence, or as a force for social control are difficult to address through strict measurement techniques. Critics of content analysis, in fact, have objected to the kind of social science that reduces culture to acts of counting. Such criticism has addressed the tendency by some researchers to favor measurement accuracy over intellectual discipline and inquiry.19

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Wedding Media and the Meaning of the Perfect Wedding Day

According to media researcher Erika Engstrom, the bridal industry in the United States generates $50 to $70 billion annually, with more than two million marriages a year.1 Supporting that massive industry are books, magazines, Web sites, reality TV shows, and digital games (in addition to fictional accounts in movies and music) that promote the idea of what a “perfect” wedding should be. What values are wrapped up in these wedding narratives?

1 DESCRIPTION. Select three or four bridal media and compare them. Possible choices include magazines such as Brides, Bridal Guide, and Martha Stewart Weddings; reality TV shows like My Fair Wedding, Bridezillas, Say Yes to the Dress, My Big Fat American Gypsy Wedding, and Four Weddings; Web sites like The Knot, Southern Bride, and Project Wedding; and games like My Fantasy Wedding, Wedding Dash, and Imagine Wedding Designer.

2 ANALYSIS. What patterns do you find in the wedding media? (Consider what isn’t depicted as well.) Are there limited ways in which femininity is defined? Do men have an equal role in the planning of wedding events? Are weddings depicted as something just for heterosexuals? Do the wedding media presume that weddings are first-

3 INTERPRETATION. What do the wedding media seem to say about what it is to be a woman or a man on her or his wedding day? What do these gender roles for the wedding suggest about the appropriate gender roles for married life after the wedding? What do the wedding media infer about the appropriate level of consumption? In other words, consider the role of wedding media in constructing hegemony: In their depiction of what makes a perfect wedding, do the media stories attempt to get us to accept the dominant cultural values relating to things like gender relations and consumerism?

4 EVALUATION. Come to a judgment about the wedding media analyzed. Are they good or bad on certain dimensions? Do they promote gender equality? Do they promote marriage equality (that is, gay marriage)? Do they offer alternatives to having a “perfect” day without buying all the trappings of so many weddings?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Talk to friends about what weddings are supposed to celebrate, and whether an alternative conception of a wedding would be a better way of celebrating a union of two people. (In real life, if there is discomfort in talking about alternative ways to celebrate a wedding, that’s probably the pressure of hegemony. Why is that pressure so strong?) Share your criticisms and ideas on wedding Web sites as well.

Contemporary Media Effects Theories

By the 1960s, the first departments of mass communication began graduating Ph.D.-level researchers schooled in experiment and survey research techniques, as well as content analysis. These researchers began documenting consistent patterns in mass communication and developing new theories. Five of the most influential contemporary theories that help explain media effects are social learning theory, agenda-

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORIES

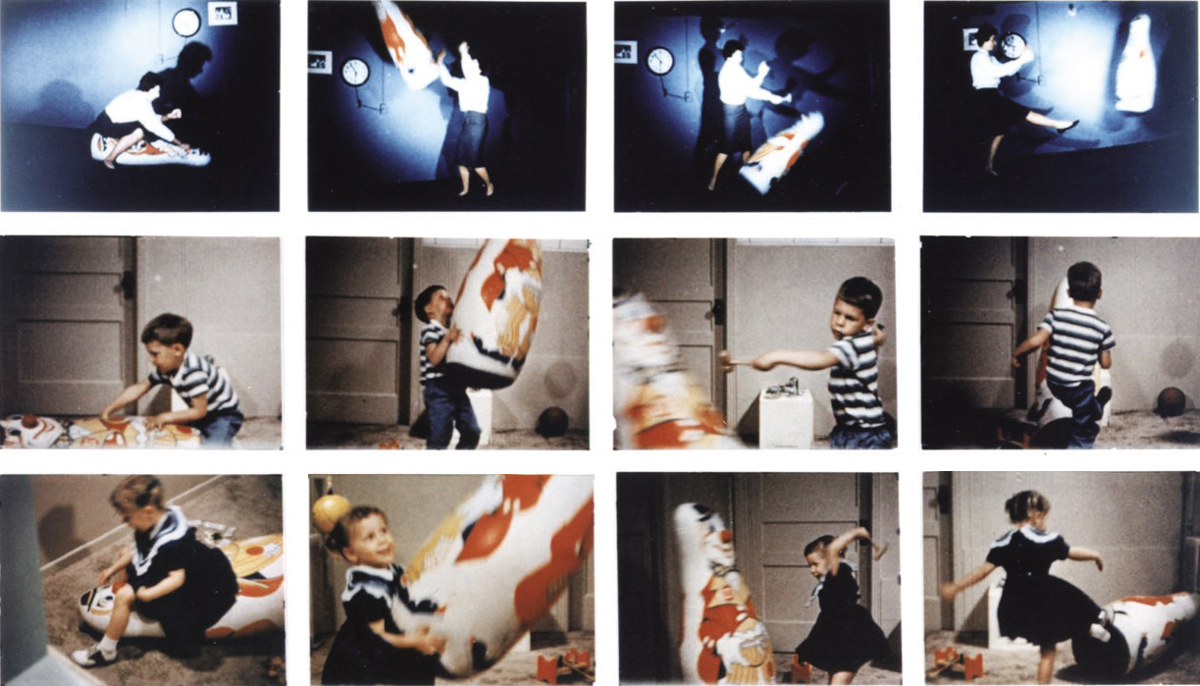

These photos document the “Bobo doll” experiments conducted by Albert Bandura and his colleagues at Stanford University in the early 1960s. Seventy-

Social Learning Theory

Some of the most well-

Supporters of social learning theory often cite real-

Agenda-

MALI

The West African nation of Mali has been in the midst of a political crisis since its northern region was seized by rebel forces in 2012. One of the most devastating outcomes of the country’s political strife is the recruitment of child soldiers, as desperate, poor families often give up their children to rebels in exchange for food and money. Despite the devastation in Mali, many feel the international response to Mali’s crisis has been woefully inadequate and the mass media’s coverage equally insufficient. AP Photo/Baba Ahmed

A key phenomenon posited by contemporary media effects researchers is agenda-

Over the years, agenda-

The Cultivation Effect

Another mass media phenomenon—

The major research in this area grew from the attempts of George Gerbner and his colleagues to make generalizations about the impact of televised violence. The cultivation effect suggests that the more time individuals spend viewing television and absorbing its viewpoints, the more likely their views of social reality will be “cultivated” by the images and portrayals they see on television.21 For example, Gerbner’s studies concluded that although fewer than 1 percent of Americans are victims of violent crime in any single year, people who watch a lot of television tend to overestimate this percentage. Such exaggerated perceptions, Gerbner and his colleagues argued, are part of a “mean world” syndrome, in which viewers with heavy, long-

According to the cultivation effect, media messages interact in complicated ways with personal, social, political, and cultural factors; they are one of a number of important factors in determining individual behavior and defining social values. Some critics have charged that cultivation research has provided limited evidence to support its findings. In addition, some have argued that the cultivation effects recorded by Gerbner’s studies have been so minimal as to be benign and that when compared side by side, the perceptions of heavy television viewers and nonviewers in terms of the “mean world” syndrome are virtually identical.

The Spiral of Silence

Developed by German communication theorist Elisabeth Noelle-

According to the theory, the mass media can help create a false, overrated majority; that is, a true majority of people holding a certain position can grow silent when they sense an opposing majority in the media. One criticism of the theory is that some people may fail to fall into a spiral of silence either because they don’t monitor the media or because they mistakenly perceive that more people hold their position than really do. Noelle-

The Third-

Identified in a 1983 study by W. Phillips Davison, the third-

Under this theory, we might fear that other people will, for example, take tabloid newspapers seriously, imitate violent movies, or get addicted to the Internet, while dismissing the idea that any of those things could happen to us. It has been argued that the third-

Evaluating Research on Media Effects

The mainstream models of media research have made valuable contributions to our understanding of the mass media, submitting content and audiences to rigorous testing. This wealth of research exists partly because funding for studies on the effects of the media on young people remains popular among politicians and has drawn ready government support since the 1960s. Media critic Richard Rhodes argues that media effects research is inconsistent and often flawed but continues to resonate with politicians and parents because it offers an easy-

Funding restricts the scope of some media effects and survey research, particularly if government, business, or other administrative agendas do not align with researchers’ interests. Other limits also exist, including the inability to address how media affect communities and social institutions. Because most media research operates best when examining media and individual behavior, fewer research studies explore media’s impact on community and social life. Some research has begun to address these deficits and also to turn more attention to the increasing impact of media technology on international communication.