Surveying the Cultural Landscape

Some cultural phenomena gain wide popular appeal, and others do not. Some appeal to certain age groups or social classes. Some, such as rock and roll, jazz, and classical music, are popular worldwide; other cultural forms, such as Tejano, salsa, and Cajun music, are popular primarily in certain regions or ethnic communities. Certain aspects of culture are considered elite in one place (e.g., opera in the United States) and popular in another (e.g., opera in Italy). Though categories may change over time and from one society to another, two metaphors offer contrasting views about the way culture operates in our daily lives: culture as a hierarchy, represented by a skyscraper model, and culture as a process, represented by a map model.

Culture as a Skyscraper

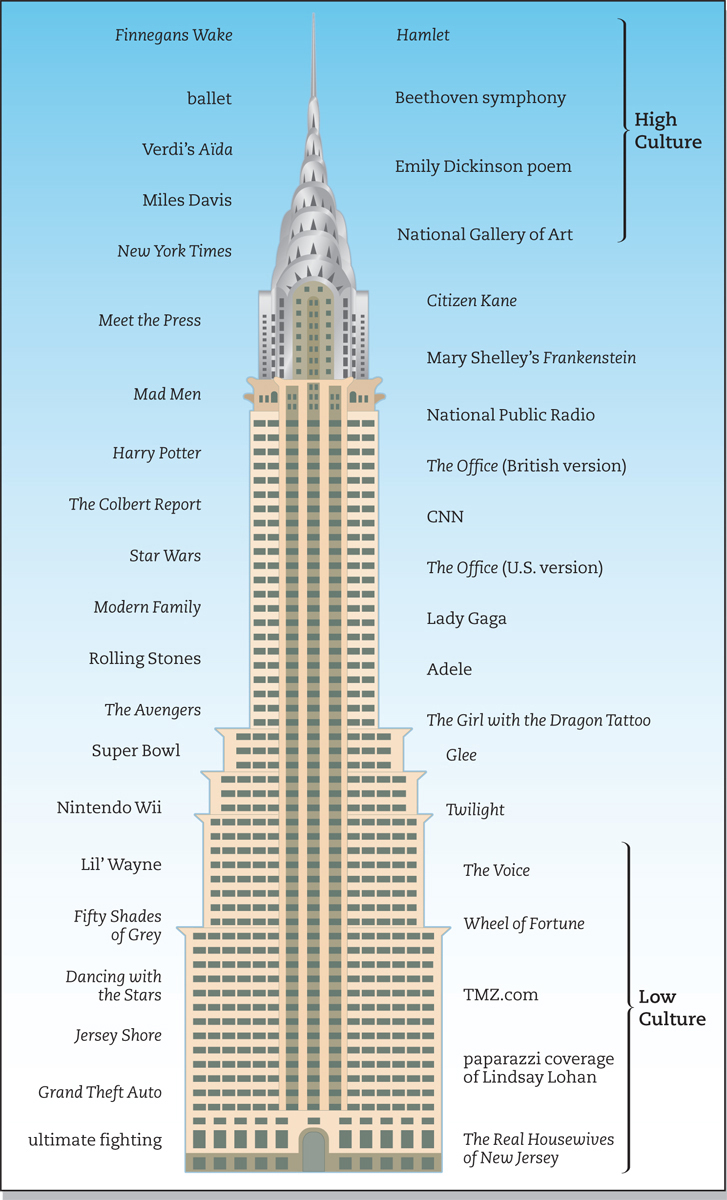

Throughout twentieth-

FIGURE 1.2 CULTURE AS A SKYSCRAPERCulture is diverse and difficult to categorize. Yet throughout the twentieth century, we tended to think of culture not as a social process but as a set of products sorted into high, low, or middle positions on a cultural skyscraper. Look at this highly arbitrary arrangement and see if you agree or disagree. Write in some of your own examples. Why do we categorize or classify culture in this way? Who controls this process? Is control of making cultural categories important? Why or why not?

An Inability to Appreciate Fine Art

Some critics claim that popular culture, in the form of contemporary movies, television, and music, distracts students from serious literature and philosophy, thus stunting their imagination and undermining their ability to recognize great art.16 This critical view pits popular culture against high art, discounting a person’s ability to value Bach and the Beatles or Shakespeare and The Simpsons concurrently. The assumption is that because popular forms of culture are made for profit, they cannot be experienced as valuable artistic experiences in the same way as more elite art forms, such as classical ballet, Italian opera, modern sculpture, or Renaissance painting—

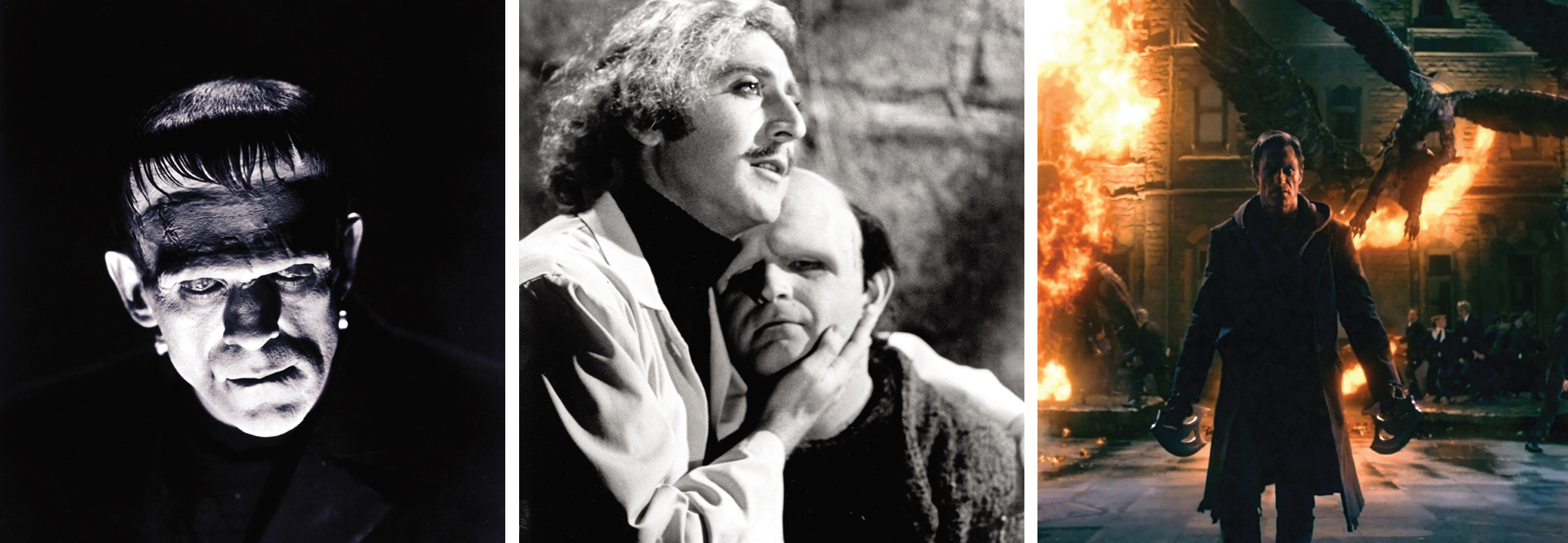

A Tendency to Exploit High Culture

Another concern is that popular culture exploits classic works of literature and art. A good example may be Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s dark Gothic novel Frankenstein, written in 1818 and ultimately transformed into multiple popular forms. Today, the tale is best remembered by virtue of two movies: a 1931 film version starring Boris Karloff as the towering and tragic monster, and the 1974 Mel Brooks comedy Young Frankenstein. In addition to the many cinematic versions, television turned the tale into The Munsters, a mid-

EXPLOITING HIGH CULTURE

Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, might not recognize our popular culture’s mutations of her Gothic classic. First published in 1818, the novel has inspired numerous interpretations, everything from the scary—

A Throwaway Ethic

Unlike an Italian opera or a Shakespearean tragedy, many elements of popular culture have a short life span. The average newspaper circulates for about twelve hours, then lands in a recycling bin; a hit song might top the charts for a few weeks at a time; and most new Web sites or blogs are rarely visited and doomed to oblivion. Although endurance does not necessarily denote quality, many critics think that so-

EXAMINING ETHICS

Covering War

By 2014, as the United States withdrew most of its military forces from Afghanistan—

When President Obama took office in 2009, he suspended the previous Bush administration ban on media coverage of soldiers’ coffins returning to U.S. soil from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. First Amendment advocates praised Obama’s decision, although after a flurry of news coverage of these arrivals in April 2009, media outlets grew less interested as the wars dragged on. Later, though, the Obama administration upset some of the same First Amendment supporters when it withheld more prisoner and detainee abuse photos from earlier in the wars, citing concerns for the safety of current U.S. troops and fears of further inflaming anti-

In May 2011, these issues surfaced again when U.S. Navy SEALs killed Osama bin Laden, long credited with perpetrating the 9/11 tragedy. As details of the SEAL operation began to emerge, the Obama administration weighed the appropriateness of releasing photos of bin Laden’s body and video of his burial at sea. While some news organizations and First Amendment advocates demanded the release of the photos, the Obama administration ultimately decided against it, saying that the government did not want to spur any further terrorist actions against the United States and its allies.

IMAGES OF WAR

The photos and images that news outlets choose to show greatly influence their audience members’ opinions. In each of the photos below, what message about war is being portrayed? How much freedom do you think news outlets should have in showing potentially controversial scenes from war? Wissam al-

How much freedom should the news media have to cover a war?

Back in 2006, President George W. Bush criticized the news media for not showing enough “good news” about U.S. efforts to bring democracy to Iraq. Bush’s remarks raised ethical questions about the complex relationship between the government and the news media during times of war: How much freedom should the news media have to cover a war? How much control, if any, should the military have over reporting a war? Are there topics that should not be covered?

These kinds of questions have also created ethical quagmires for local TV stations that cover war and its effects on communities where soldiers have been called to duty and then injured or killed. In one extreme case, the nation’s largest TV station owner—

Sinclair Broadcast Group, one of the largest owners of local television stations, will preempt tonight’s edition of the ABC News program “Nightline,” saying the program’s plan to have Ted Koppel [who then anchored the program] read aloud the names of every member of the armed forces killed in action in Iraq was motivated by an antiwar agenda and threatened to undermine American efforts there.

The decision means viewers in eight cities, including St. Louis and Columbus, Ohio, will not see “Nightline.” ABC News disputed that the program carried a political message, calling it “an expression of respect which simply seeks to honor those who have laid down their lives for their country.”

But Mark Hyman, the vice president of corporate relations for Sinclair, who is also a conservative commentator on the company’s newscasts, said tonight’s edition of “Nightline” is biased journalism. “Mr. Koppel’s reading of the fallen will have no proportionality,” he said in a telephone interview, pointing out that the program will ignore other aspects of the war effort.

Mr. Koppel and the producers of “Nightline” said earlier this week that they had no political motivation behind the decision to devote an entire show, expanded to 40 minutes, to reading the names and displaying the photos of those killed. They said they only intended to honor the dead and document what Mr. Koppel called “the human cost” of the war.1

Given such a case, how might a local TV news director today—

Arriving at ethical decisions is a particular kind of criticism involving several steps. These include (1) laying out the case; (2) pinpointing the key issues; (3) identifying the parties involved, their intents, and their potentially competing values; (4) studying ethical models and theories; (5) presenting strategies and options; and (6) formulating a decision or policy.2

As a test case, let’s look at how local TV news directors might establish ethical guidelines for war-

Examining Ethics Activity

As a class or in smaller groups, design policies that address one or more of the issues raised here. Start by researching the topic; find as much information as possible. For example, you can research guidelines that local stations already use by contacting local news directors and TV journalists.

Do the local stations have guidelines? If so, are they adequate? Are there certain types of images they will not show? If the Obama administration had released photographic evidence of bin Laden’s death, would a local station have shown it? Finally, if time allows, send the policies you designed to various TV news directors and/or station managers; ask for their evaluations, and ask whether they would consider implementing the policies.

A Diminished Audience for High Culture

Some observers also warn that popular culture has inundated the cultural environment, driving out higher forms of culture and cheapening public life.17 This concern is supported by data showing that TV sets are in use in the average American home for nearly eight hours a day, exposing adults and children each year to thousands of hours of trivial TV commercials, violent crime dramas, and superficial reality programs. According to one story critics tell, the prevalence of so many popular media products prevents the public from experiencing genuine art—

Dulling Our Cultural Taste Buds

One cautionary story, frequently recounted by academics, politicians, and pundits, tells how popular culture, especially its more visual forms (such as TV advertising and YouTube videos), undermines democratic ideals and reasoned argument. According to this view, popular media may inhibit not only rational thought but also social progress by transforming audiences into cultural dupes lured by the promise of products. A few multinational conglomerates that make large profits from media products may be distracting citizens from examining economic disparity and implementing change. Seductive advertising images showcasing the buffed and airbrushed bodies of professional models, for example, frequently contradict the actual lives of people who cannot hope to achieve a particular “look” or may not have the money to obtain the high-

CASE STUDY

Is Anchorman a Comedy or a Documentary?

One fascinating media phenomenon of the first few decades of the twenty-

Why is this?

They are both media products that depend on storytelling to draw audiences and make money. But while complex and controversial TV narratives like HBO’s Game of Thrones, Showtime’s Penny Dreadful, FX’s Fargo, AMC’s Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead, Netflix’s House of Cards, and NBC’s The Blacklist were not possible in the 1960s, when just three networks—

The reason for the lack of advances in news narratives is itself a story—

American filmmakers from D. W. Griffith and Orson Welles to Steven Spielberg and Wes Anderson have understood the allure of narrative. But narrative is such a large category—

Gemma LaMana/© Paramount Pictures/Everett Collection

In fact, most local and national TV news stories function as a kind of melodrama as defined by Cawelti and others. In the melodrama, “the city” is often the setting—

The appropriation of these narratives by news shows has been satirized by the likes of Anchorman, Saturday Night Live, and, more pointedly, Comedy Central’s The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. These satires often critique the way news producers repeat stale formulas rather than invent dynamic new story forms for new generations of viewers. As much as the world has changed since the 1970s (when SNL’s “Weekend Update” debuted), local TV news story formulas have gone virtually unaltered. Modern newscasts still limit reporters’ stories to two minutes or less and promote stylish male/female anchor teams, a sports “guy,” and a certified meteorologist as familiar personalities, usually leading with a dramatic local crime story and teasing viewers to stay tuned for a possible weather disaster.

By indulging these formulas, TV news continues to address viewers not primarily as citizens and members of communities but as news consumers who build the TV ratings that determine the ad rates for local stations and the national networks. In the book The Elements of Journalism, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel argue that “journalists must make the significant interesting and relevant.”2 Too often, however, on cable, the Internet, and local news, we are awash in news stories that try to make something significant out of the obviously trivial, mildly interesting, or narrowly relevant—

In fictional TV, however, storytelling has evolved over time, becoming increasingly dynamic and complex with shows like Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, The Good Wife, Fargo, Homeland, and Girls. In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that in contrast to older popular 1970s programs like Dallas or Dynasty, the best TV stories today layer “each scene with a thick network of affiliations. You have to focus to follow the plot, and in focusing you’re exercising the parts of your brain that map social networks, that fill in missing information, that connect multiple narrative threads.”3 Johnson says that younger audiences today—

Dana Edelson/NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images

This evolution of fictional storytelling has not yet happened with its nonfictional counterparts; TV news remains entrenched in old formulas and time constraints. The reasons for this, of course, are money and competition. Whereas national networks today have begun to adjust their programming decisions to better compete against cable services like AMC and HBO and new story “content” providers like Netflix and Amazon, local TV news still competes against just three or four other news stations and just one (if any) local newspaper. Even with diminished viewership (most local TV stations have lost half their audience over the past ten to fifteen years), local TV news still draws enough viewers in a fragmented media landscape to attract top ad dollars.

But those viewership levels continue to decline as older audiences give way to new generations more likely to comb social media networks for news and information. Perhaps younger audiences crave news stories that match the more complicated storytelling that surrounds them in everything from TV dramas to interactive video games to their own conversations. Viewers raised on the irony of Saturday Night Live, The Simpsons, Family Guy, South Park, and The Daily Show are not buying—

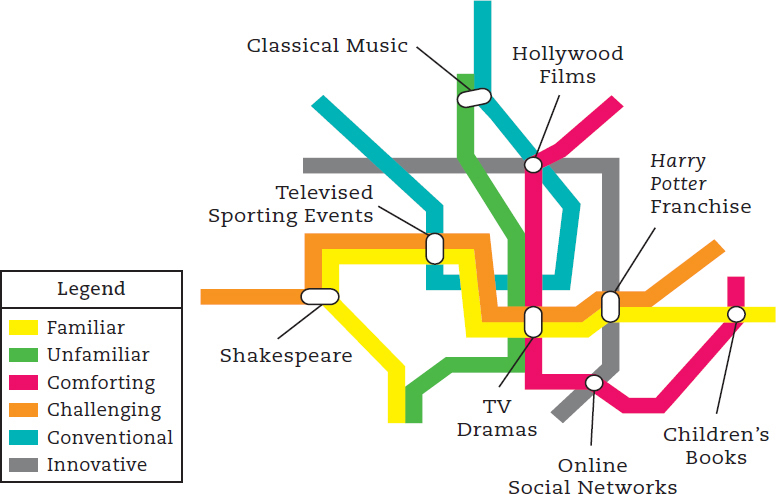

Culture as a Map

While the skyscraper model is one way to view culture, another way to view it is as a map. Here, culture is an ongoing and complicated process—

THE POPULAR HUNGER GAMES book series, which has also become a blockbuster film franchise, mixes elements that have, in the past, been considered “low” culture (young-

Our attraction to and choice of cultural phenomena—

FIGURE 1.3 CULTURE AS A MAP In this map model, culture is not ranked as high or low. Instead, the model shows culture as spreading out in several directions across a variety of dimensions. For example, some cultural forms can be familiar, innovative, and challenging, like the Harry Potter books and movies. This model accounts for the complexity of individual tastes and experiences. The map model also suggests that culture is a process by which we produce meaning—

The Comfort of Familiar Stories

The appeal of culture is often its familiar stories, pulling audiences toward the security of repetition and common landmarks on the cultural map. Consider, for instance, early television’s Lassie series, about the adventures of a collie named Lassie and her owner, young Timmy. Of the more than five hundred episodes, many have a familiar and repetitive plotline: Timmy, who arguably possessed the poorest sense of direction and suffered more concussions than any TV character in history, gets lost or knocked unconscious. After finding Timmy and licking his face, Lassie goes for help and saves the day. Adult critics might mock this melodramatic formula, but many children found comfort in the predictability of the story. This quality is also evident when night after night children ask their parents to read them the same book, such as Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon or Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, or watch the same DVD, such as Snow White or The Princess Bride.

Innovation and the Attraction of “What’s New”

Like children, adults also seek comfort, often returning to an old Beatles or Guns N’ Roses song, a William Butler Yeats or Emily Dickinson poem, or a TV rerun of Seinfeld or Andy Griffith. But we also like cultural adventure. We may turn from a familiar film on cable’s AMC to discover a new movie from Iran or India on the Sundance Channel. We seek new stories and new places to go—

A Wide Range of Messages

We know that people have complex cultural tastes, needs, and interests based on different backgrounds and dispositions. It is not surprising, then, that our cultural treasures, from blues music and opera to comic books and classical literature, contain a variety of messages. Just as Shakespeare’s plays—

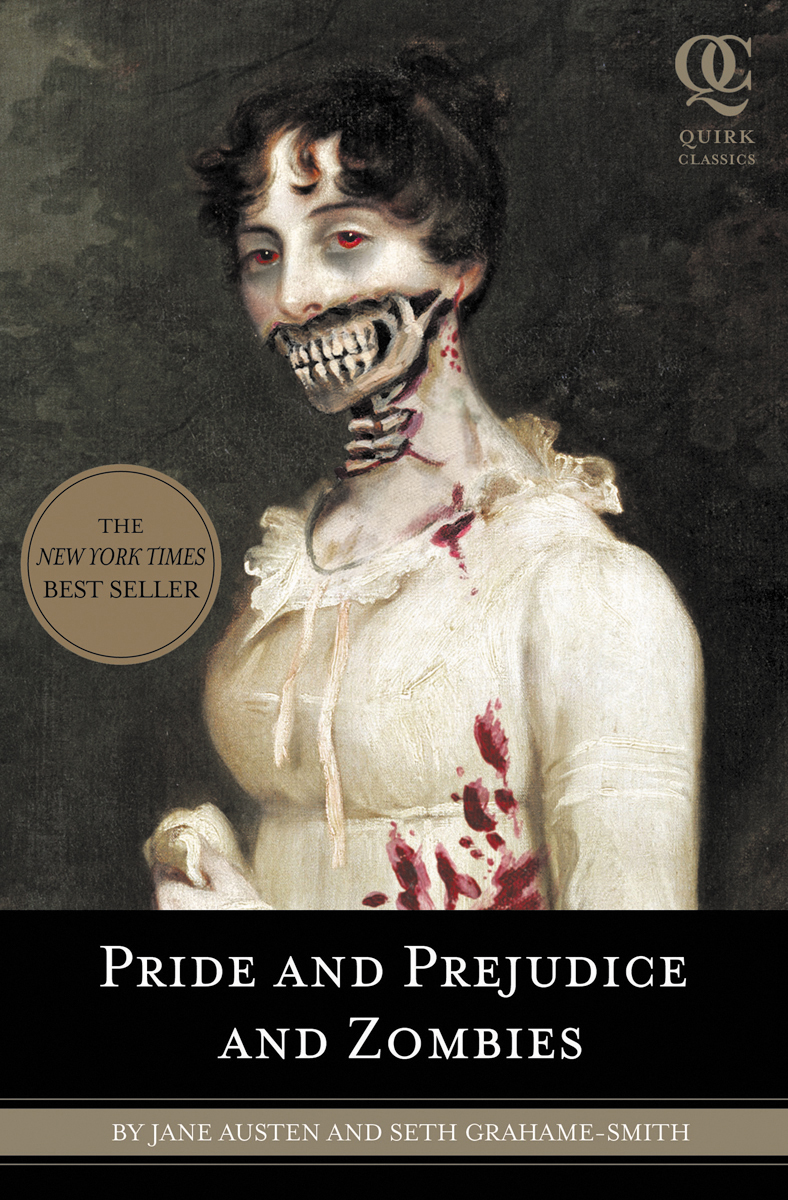

Challenging the Nostalgia for a Better Past

PRIDEANDPREJUDICE AND ZOMBIES is a famous “mash-

Some critics of popular culture assert—

Throughout history, a call to return to familiar terrain, to “the good old days,” has been a frequent response to new, “threatening” forms of popular culture or to any ideas that are different from what we already believe. Yet over the years many of these forms, including the waltz, silent movies, ragtime, and jazz, have themselves become cultural “classics.” How can we tell now what the future has in store for such cultural expressions as rock and roll, soap operas, fashion photography, dance music, hip-

Cultural Values of the Modern Period

To understand how the mass media have come to occupy their current cultural position, we need to trace significant changes in cultural values from the modern period until today. In general, U.S. historians and literary scholars think of the modern period as beginning with the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century and extending until about the mid-

Modernization involved captains of industry using new technology to create efficient manufacturing centers, produce inexpensive products to make everyday life better, and make commerce more profitable. Printing presses and assembly lines made major contributions in this transformation, and then modern advertising spread the word about new gadgets to American consumers. In terms of culture, the modern mantra has been “form follows function.” For example, the growing populations of big cities placed a premium on space, creating a new form of building that fulfilled that functional demand by building upwards. Modern skyscrapers made of glass, steel, and concrete replaced the supposedly wasteful decorative and ornate styles of premodern Gothic cathedrals. This new value was echoed in journalism, where a front-

Cultural responses to and critiques of modern efficiency often manifested themselves in the mass media. For example, in Brave New World (1932), Aldous Huxley created a fictional world in which he cautioned readers that the efficiencies of modern science and technology posed a threat to individual dignity. Charlie Chaplin’s film Modern Times (1936), set in a futuristic manufacturing plant, also told the story of the dehumanizing impact of modernization and machinery. Writers and artists, in their criticisms of the modern world, have often pointed to technology’s ability to alienate people from one another, capitalism’s tendency to foster greed, and government’s inclination to create bureaucracies whose inefficiency oppresses rather than helps people.

While the values of the premodern period (before the Industrial Revolution) were guided by a strong belief in a natural or divine order, modernization elevated individual self-

To be modern also meant valuing the ability of logical and scientific minds to solve problems by working in organized groups and expert teams. Progressive thinkers maintained that the printing press, the telegraph, and the railroad, in combination with a scientific attitude, would foster a new type of informed society. At the core of this society, the printed mass media—

A leading champion for an informed rational society was Walter Lippmann, who wrote the influential book Public Opinion in 1922. He distrusted both the media and the public’s ability to navigate a world that was “altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance,” and to reach the rational decisions needed in a democracy. Instead, he advocated a “machinery of knowledge” that might be established through “intelligence bureaus” staffed by experts. While such a concept might look like the modern think tank, Lippmann saw these as independent of politics, unlike think tanks today, such as the Brookings Institution or the Heritage Foundation, which have strong partisan ties.19

Walter Lippmann’s ideas were influential throughout the twentieth century and were a product of the Progressive Era—a period of political and social reform that lasted roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s. On both local and national levels, Progressive Era reformers championed social movements that led to constitutional amendments for both Prohibition and women’s suffrage, political reforms that led to the secret ballot during elections, and economic reforms that ushered in the federal income tax to try to foster a more equitable society. Muckrakers—

Influenced by the Progressive movement, the notion of being modern in the twentieth century meant throwing off the chains of the past, breaking with tradition, and embracing progress. For example, twentieth-

Shifting Values in Postmodern Culture

For many people, the changes occurring in the postmodern period—from roughly the mid-

| Trend | Premodern (pre- |

Modern Industrial Revolution (1800s- |

Postmodern (1950s- |

| Work hierarchies | peasants/merchants/rulers | factory workers/managers/national CEOs | temp workers/global CEOs |

| Major work sites | field/farm | factory/office | office/home/“virtual” or mobile office |

| Communication reach | local | national | global |

| Communication transmission | oral/manuscript | print/electronic | electronic/digital |

| Communication channels | storytellers/elders/town criers | books/newspapers/magazines/radio | television/cable/Internet/multimedia |

| Communication at home | quill pen | typewriter/office computer | personal computer/laptop/smartphone/social networks |

| Key social values | belief in natural or divine order | individualism/rationalism/efficiency/antitradition | antihierarchy/skepticism (about science, business, government, etc.)/diversity/multiculturalism/irony & paradox |

| Journalism | oral & print- |

print- |

TV- |

Table 1.1: TABLE 1.1 TRENDS ACROSS HISTORICAL PERIODS

As a political idea, populism tries to appeal to ordinary people by highlighting or even creating an argument or conflict between “the people” and “the elite.” In virtually every campaign, populist politicians often tell stories and run ads that criticize big corporations and political favoritism. Meant to resonate with middle-

In postmodern culture, populism has manifested itself in many ways. For example, artists and performers, like Chuck Berry in “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956) or Queen in “Bohemian Rhapsody” (1975), intentionally blurred the border between high and low culture. In the visual arts, following Andy Warhol’s 1960s pop art style, advertisers have borrowed from both fine art and street art, while artists appropriated styles from commerce and popular art. Film stars, like Angelina Jolie and Ben Affleck, often champion oppressed groups while appearing in movies that make the actors wealthy global icons of consumer culture.

Other forms of postmodern style blur modern distinctions not only between art and commerce but also between fact and fiction. For example, television vocabulary now includes infotainment (such as Entertainment Tonight and Access Hollywood) and infomercials (such as fading celebrities selling antiwrinkle cream). On cable, MTV’s reality programs—

Closely associated with populism, another value (or vice) of the postmodern period is the emphasis on diversity and fragmentation, including the wild juxtaposition of old and new cultural styles. In a suburban shopping mall, for instance, Gap stores border a food court with Vietnamese, Italian, and Mexican options, while techno-

Another tendency of postmodern culture involves rejecting rational thought as “the answer” to every social problem, reveling instead in nostalgia for the premodern values of small communities, traditional religion, and even mystical experience. Rather than seeing science purely as enlightened thinking or rational deduction that relies on evidence, some artists, critics, and politicians criticize modern values for laying the groundwork for dehumanizing technological advances and bureaucratic problems. For example, in the renewed debates over evolution, one cultural narrative that plays out often pits scientific evidence against religious belief and literal interpretations of the Bible. And in popular culture, many TV programs—

Lastly, the fourth aspect of our postmodern time is the willingness to accept paradox. While modern culture emphasized breaking with the past in the name of progress, postmodern culture stresses integrating—

Although, as modernists warned, new technologies can isolate people or encourage them to chase their personal agendas (e.g., a student perusing his individual interests online), new technologies can also draw people together to advance causes; to solve community problems; or to discuss politics on radio talk shows, Facebook, or smartphones. For example, in 2011 and 2012, Twitter made the world aware of protesters in many Arab nations, including Egypt and Libya, when governments there tried to suppress media access. Our lives today are full of such incongruities.

FILMS OFTEN REFLECT THE KEY SOCIAL VALUES of an era—