A Changing Industry: Reformations in Popular Music

As the 1960s began, rock and roll was tamer and “safer,” as reflected in the surf and road music of the Beach Boys and Jan & Dean, but it was also beginning to branch out. For instance, the success of all-

The British Are Coming!

The global trade of pop music is evident in the exchanges and melding of rhythms, beats, vocal styles, and musical instruments across cultures. The origin of this global impact can be traced to England in the late 1950s, when the young Rolling Stones listened to the blues of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, and the young Beatles tried to imitate Chuck Berry and Little Richard.

Until 1964, rock-

With the British invasion, “rock and roll” unofficially became “rock,” sending popular music and the industry in two directions. On the one hand, the Rolling Stones would influence generations of musicians emphasizing gritty, chord-

BRITISH ROCK GROUPS

Ed Sullivan, who booked the Beatles several times on his TV variety show in 1964, helped promote their early success. Sullivan, though, reacted differently to the Rolling Stones, who were perceived as the “bad boys” of rock and roll in contrast to the “good” Beatles. The Stones performed black-

Motor City Music: Detroit Gives America Soul

Ironically, the British invasion, which drew much of its inspiration from black influences, drew many white listeners away from a new generation of black performers. Gradually, however, throughout the 1960s, black singers like James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Ike and Tina Turner, and Wilson Pickett found large and diverse audiences. Transforming the rhythms and melodies of older R&B, pop, and early rock and roll into what became labeled as soul, they countered the British invaders with powerful vocal performances. Mixing gospel and blues with emotion and lyrics drawn from the American black experience, soul contrasted sharply with the emphasis on loud, fast instrumentals and lighter lyrical concerns that characterized much of rock music.18

The most prominent independent label that nourished soul and black popular music was Motown, started in 1959 by former Detroit autoworker and songwriter Berry Gordy with a $700 investment and named after Detroit’s “Motor City” nickname. Beginning with Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “Shop Around,” Motown enjoyed a long string of hit records that rivaled the pop success of British bands throughout the decade. Motown’s many successful artists included the Temptations (“My Girl”), Mary Wells (“My Guy”), the Four Tops (“I Can’t Help Myself”), Martha and the Vandellas (“Heat Wave”), Marvin Gaye (“I Heard It through the Grapevine”), and, in the early 1970s, the Jackson 5 (“ABC”). But the label’s most successful group was the Supremes, featuring Diana Ross, which scored twelve No. 1 singles between 1964 and 1969 (“Where Did Our Love Go,” “Stop! In the Name of Love”). The Motown groups had a more stylized, softer sound than the grittier southern soul (later known as funk) of Brown and Pickett.

Folk and Psychedelic Music Reflect the Times

Popular music has always been a product of its time, so the social upheavals of the Civil Rights movement, the women’s movement, the environmental movement, and the Vietnam War naturally brought social concerns into the music of the 1960s and early 1970s. By the late 1960s, the Beatles had transformed themselves from a relatively lightweight pop band to one that spoke for the social and political concerns of their generation, and many other groups followed the same trajectory. (To explore how the times and personal taste influence music choices, see “Media Literacy and the Critical Process: Music Preferences across Generations” on page 132.)

THE SUPREMES

One of the most successful groups in rock-

Folk Inspires Protest

BOB DYLAN

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman in Minnesota, Bob Dylan took his stage name from Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. He led a folk music movement in the early 1960s with engaging, socially provocative lyrics. He was also an astute media critic, as is evident in the seminal documentary Don’t Look Back (1967). Andrew DeLory

The musical genre that most clearly responded to the political happenings of the time was folk music, which had long been the sound of social activism. In its broadest sense, folk music in any culture refers to songs performed by untrained musicians and passed down mainly through oral traditions, from the banjo and fiddle tunes of Appalachia to the accordion-

Rock Turns Psychedelic

Alcohol and drugs have long been associated with the private lives of blues, jazz, country, and rock musicians. These links, however, became much more public in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when authorities busted members of the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. With the increasing role of drugs in youth culture and the availability of LSD (not illegal until the mid-

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Music Preferences across Generations

We make judgments about music all the time. Older generations don’t like some of the music younger people prefer, and young people often dismiss some of the music of previous generations. Even among our peers, we have different tastes in music and often reject certain kinds of music that have become too popular or that don’t conform to our own preferences. The following exercise aims to understand musical tastes beyond our own individual choices. Be sure to include yourself in this project.

1 DESCRIPTION. Arrange to interview four to eight friends or relatives of different ages about their musical tastes and influences. Devise questions about what music they listen to and have listened to at different stages of their lives. What music do they buy or collect? What’s the first album (or single) they acquired? What’s the latest album? What stories or vivid memories do they relate to particular songs or artists? Collect demographic and consumer information: age, gender, occupation, educational background, place of birth, and current place of residence.

2 ANALYSIS. Chart and organize your results. Do you recognize any patterns emerging from the data or stories? What kinds of music did your interview subjects listen to when they were younger? What kinds of music do they listen to now? What formed/influenced their musical interests? If their musical interests changed, what happened? (If they stopped listening to music, note that and find out why.) Do they have any associations between music and their everyday lives? Are these music associations and lifetime interactions with songs and artists important to them?

3 INTERPRETATION. Based on what you have discovered and the patterns you have charted, determine what the patterns mean. Does age, gender, geographic location, or education matter in musical tastes? Over time, are the changes in musical tastes and buying habits significant? Why or why not? What kind of music is most important to your subjects? Finally, and most important, why do you think their music preferences developed as they did?

4 EVALUATION. Determine how your interview subjects came to like particular kinds of music. What constitutes “good” and “bad” music for them? Did their ideas change over time? How? Are they open-

5 ENGAGEMENT. To expand on your findings, consider the connections of music across generations, geography, and genres. Take a musical artist you like and input the name at www.music-map.com. Use the output of related artists to discover new bands. Input favorite artists of the people you interviewed in Step 1, and share the results with them. Expand your musical tastes.

Punk, Grunge, and Alternative Respond to Mainstream Rock

By the 1970s, rock music was increasingly viewed as just another part of mainstream consumer culture. With major music acts earning huge profits, rock soon became another product line for manufacturers and retailers to promote, package, and sell—

Punk Revives Rock’s Rebelliousness

SAVAGES

All-

Punk rock rose in the late 1970s to challenge the orthodoxy and commercialism of the record business. By this time, the glory days of rock’s competitive independent labels had ended, and rock music was controlled by just a half-

The punk movement took root in the small dive bar CBGB in New York City around bands such as the Ramones, Blondie, and the Talking Heads. (The roots of punk essentially lay in four pre-

Punk was not a commercial success in the United States, where (not surprisingly) it was shunned by radio. However, punk’s contributions continue to be felt. Punk broke down the “boy’s club” mentality of rock, launching unapologetic and unadorned frontwomen like Patti Smith, Joan Jett, Debbie Harry, and Chrissie Hynde, and it introduced all-

Grunge and Alternative Reinterpret Rock

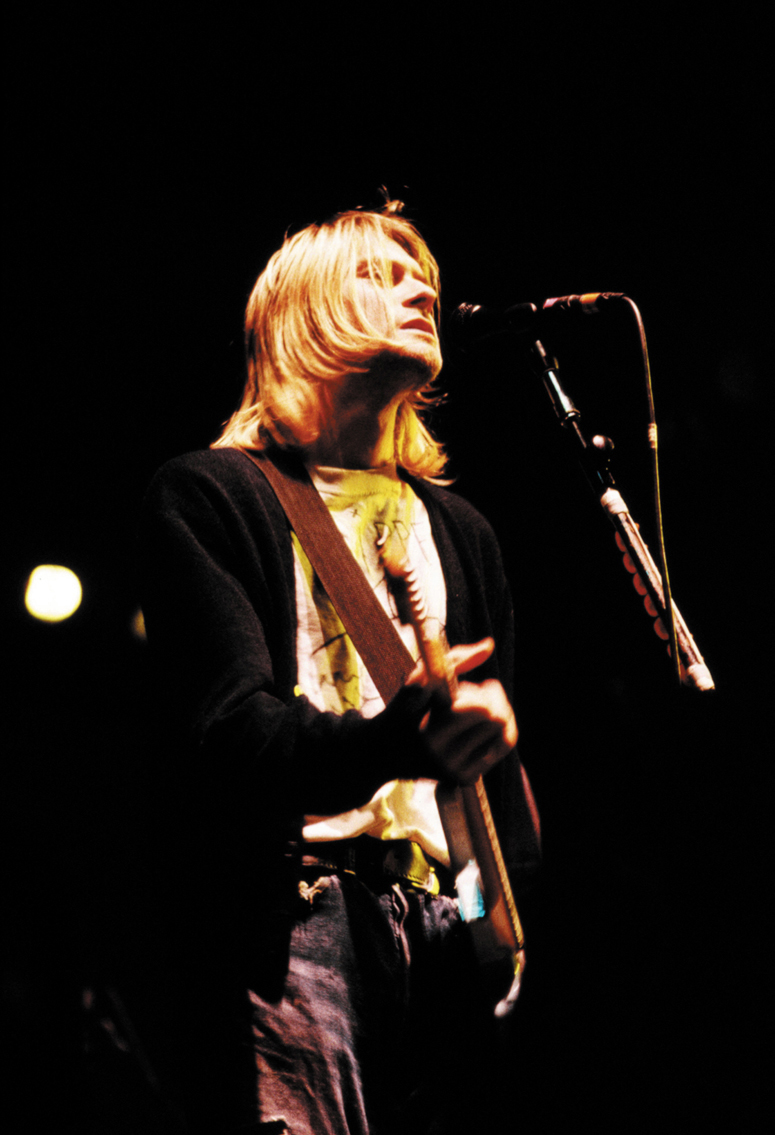

NIRVANA’S lead singer, Kurt Cobain, is pictured here during his brief career in the early 1990s. The release of Nirvana’s Nevermind in September 1991 bumped Michael Jackson’s Dangerous from the top of the charts and signaled a new direction in popular music. Other grunge bands soon followed Nirvana onto the charts, including Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Stone Temple Pilots, and Soundgarden.© Pycha/DAPR/Zuma Press

Taking the spirit of punk and updating it, the grunge scene represented a significant development in rock in the 1990s. Getting its name from its often-

In some critical circles, both punk and grunge are considered subcategories or fringe movements of alternative rock. This vague label describes many types of experimental rock music that offered a departure from the theatrics and staged extravaganzas of 1970s glam rock, which showcased such performers as David Bowie and Kiss. Appealing chiefly to college students and twentysomethings, alternative rock has traditionally opposed the sounds of Top 40 and commercial FM radio. In the 1980s and 1990s, U2 and R.E.M. emerged as successful groups often associated with alternative rock. A key dilemma for successful alternative performers, however, is that their popularity results in commercial success, ironically a situation that their music often criticizes. While alternative rock music has more variety than ever, it is also not producing new mega-

Hip-

CHANCE THE RAPPER gained an enormous following based on the self-

With the growing segregation of radio formats and the dominance of mainstream rock by white male performers, the place of black artists in the rock world diminished from the late 1970s onward. By the 1980s, few popular black successors to Chuck Berry or Jimi Hendrix had emerged in rock, though Prince and Lenny Kravitz were exceptions. These trends, combined with the rise of “safe” dance disco by white bands (the Bee Gees), black artists (Donna Summer), and integrated groups (the Village People), created a space for a new sound to emerge: hip-

In the same way that punk opposed commercial rock, hip-

The music industry initially saw hip-

On the one hand, the conversational style of rap makes it a forum in which performers can debate issues of gender, class, sexuality, violence, and drugs. On the other hand, hip-

The Reemergence of Pop

After waves of punk, grunge, alternative, and hip-

ITUNES shifted the music business toward a singles-