The Business of Sound Recording

For many in the recording industry, the relationship between music’s business and artistic elements is an uneasy one. The lyrics of hip-

Music Labels Influence the Industry

After several years of steady growth, revenues for the recording industry experienced significant losses beginning in 2000 as file-

Fewer Major Labels and Falling Market Share

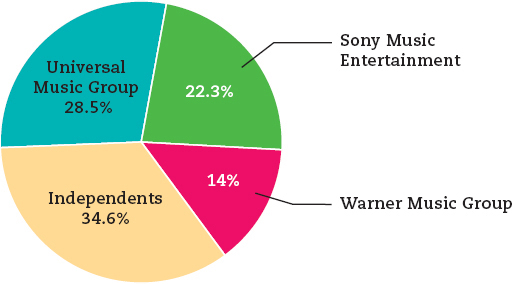

FIGURE 4.2 U.S. MARKET SHARE OF THE MAJOR LABELS IN THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, 2013 Data from: Nielsen SoundScan, 2013. Figures are rounded.

From the 1950s through the 1980s, the music industry, though powerful, consisted of a large number of competing major labels, along with numerous independent labels. Over time, the major labels began swallowing up the independents and then buying one another. By 1998, only six major labels remained—

The Indies Grow with Digital Music

The rise of rock and roll in the 1950s and early 1960s showcased a rich diversity of independent labels—

TRACKING TECHNOLOGY

The Song Machine: The Hitmakers behind Rihanna

by John Seabrook

On a mild Monday afternoon in mid-

Most of the songs played on Top Forty radio are collaborations between producers like Stargate and “top line” writers like Ester Dean. The producers compose the chord progressions, program the beats, and arrange the “synths,” or computer-

Today’s Top Forty is almost always machine-

As was the case in the pre-

Rihanna is often described as a “manufactured” pop star, because she doesn’t write her songs, but neither did Sinatra or Elvis. She embodies a song in the way an actor inhabits a role—

Source: Excerpted from John Seabrook, “The Song Machine: The Hitmakers behind Rihanna,” New Yorker, March 26, 2012, www.newyorker.com/

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

Making, Selling, and Profiting from Music

INDIE LABELS are able to take chances on artists like Majical Cloudz, an indie pop duo from Montreal signed to Matador, an independent label based in New York. Majical Cloudz gained exposure by touring in summer 2014 with Lorde, who has a contract with Universal, the largest major label. Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Like most mass media, the music business is divided into several areas, each working in a different capacity. In the music industry, those areas are making the music (signing, developing, and recording the artist), selling the music (selling, distributing, advertising, and promoting the music), and dividing the profits. All these areas are essential to the industry but have always shared in the conflict between business concerns and artistic concerns.

Making the Music

Labels are driven by A&R (artist & repertoire) agents, the talent scouts of the music business, who discover, develop, and sometimes manage artists. A&R executives scan online music sites and listen to demonstration tapes, or demos, from new artists and decide whom to sign and which songs to record. A&R executives naturally look for artists they think will sell, and they are often forced to avoid artists with limited commercial possibilities or to tailor artists to make them viable for the recording studio.

A typical recording session is a complex process that involves the artist, the producer, the session engineer, and audio technicians. In charge of the overall recording process, the producer handles most nontechnical elements of the session, including reserving studio space, hiring session musicians (if necessary), and making final decisions about the sound of the recording. The session engineer oversees the technical aspects of the recording session, everything from choosing recording equipment to managing the audio technicians. Most popular records are recorded part by part. Using separate microphones, the vocalists, guitarists, drummers, and other musical sections are digitally recorded onto separate audio tracks, which are edited and remixed during postproduction and ultimately mixed down to a two-

Selling the Music

Selling and distributing music is a tricky part of the business. For years, the primary sales outlets for music were direct-

As recently as 2011, physical recordings (CDs and some vinyl) accounted for about 50 percent of U.S. music sales. But CD sales continue to decline and now constitute about 35 percent of the market. In some other Top 10 global music markets, such as Japan and Germany, CDs are still the top format, and the cultural shift from physical recordings to digital formats is just beginning.

Conversely, digital sales—

Subscription and streaming services have been a big growth area in the United States and now account for about 21 percent of U.S. music industry revenues. The difference between a streaming music service (e.g., Spotify) and streaming radio (e.g., Pandora) is that streaming services enable listeners to stream specific songs, whereas streaming radio services allow listeners to select only a genre or style of music.

The international recording industry is a major proponent of music streaming services because they are a new revenue source. Although online piracy—unauthorized online file-

Dividing the Profits

The digital upheaval in the music industry has shaken up the once-

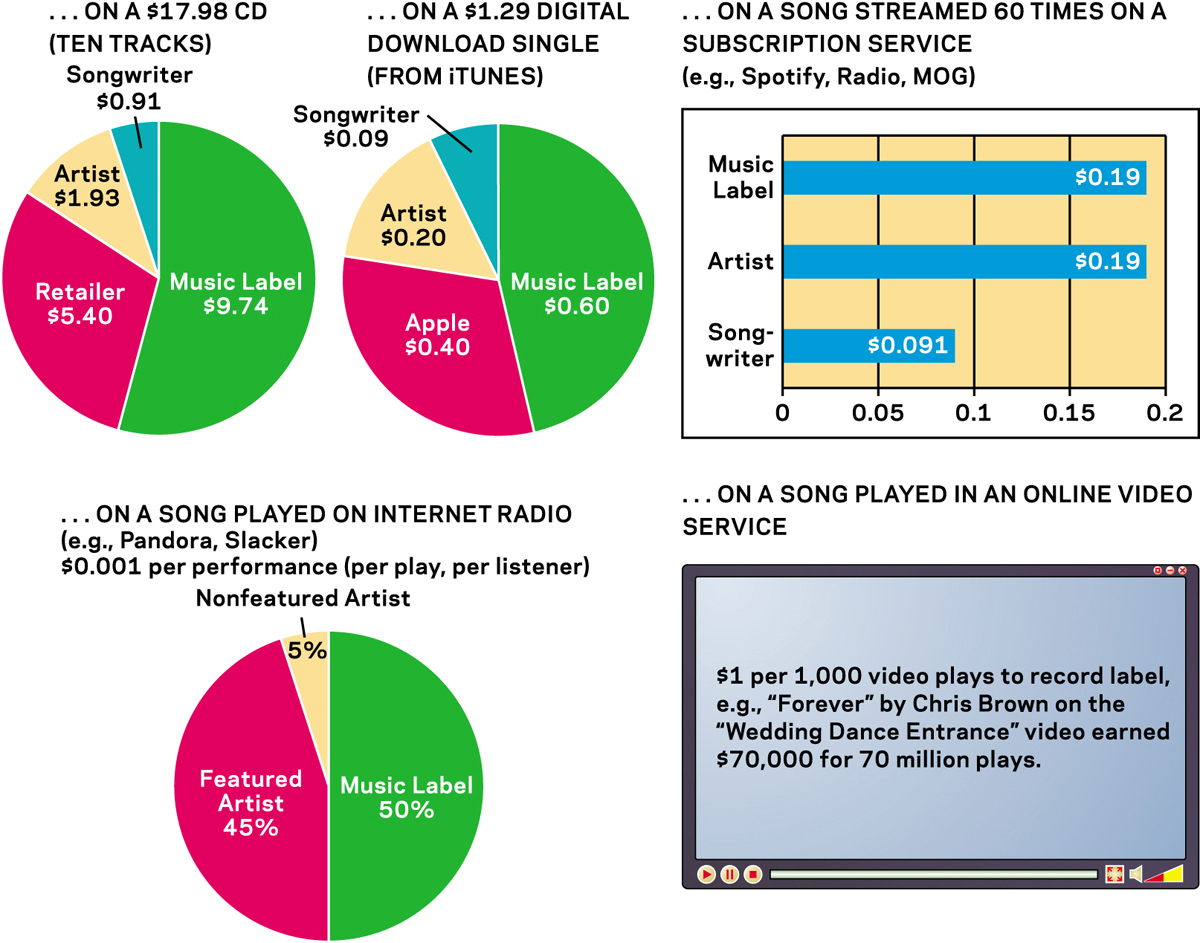

The wholesale price for that CD is about $12.50, leaving the remainder as retail profit. Discount retailers like Walmart and Best Buy sell closer to the wholesale price to lure customers to buy other things (even if they make less profit on the CD itself). The wholesale price represents the actual cost of producing and promoting the recording, plus the recording label’s profits. The record company reaps the highest revenue (close to $9.74 on a typical CD) but, along with the artist, bears the bulk of the expenses: manufacturing costs, packaging and CD design, advertising and promotion, and artists’ royalties (see Figure 4.3 on page 141). The physical product of the CD itself costs less than a quarter to manufacture.

FIGURE 4.3 WHERE THE MONEY GOES Data from: Steve Knopper, “The New Economics of the Music Industry,” Rolling Stone, October 25, 2011, www.rollingstone.com/

New artists usually negotiate a royalty rate of between 8 and 12 percent on the retail price of a CD, while more established performers might negotiate for 15 percent or higher. An artist who has negotiated a typical 11 percent royalty rate would earn about $1.93 per CD whose suggested retail price is $17.98. So a CD that “goes gold”—that is, sells 500,000 units—

The profits are divided somewhat differently in digital download sales. A $1.29 iTunes download generates about $0.40 for Apple (it gets 30 percent of every song sale) and a standard $0.09 mechanical royalty for the song publisher and writer, leaving about $0.60 for the record company. Artists at a typical royalty rate of about 15 percent would get $0.20 from the song download. With no CD printing and packaging costs, record companies can retain more of the revenue on download sales. Digital music sales also sometimes involve lucrative side deals: Jay-

LaunchPad

Alternative Strategies for Music Marketing

This video explores the strategies independent artists and marketers now employ to reach audiences.

Discussion: Even with the ability to bypass major record companies, many of the most popular artists still sign with those companies. Why do you think that is?

Another venue for digital music is streaming services like Spotify, Rdio, and Beats Music. Some leading artists initially held back their new releases from such services due to concerns that streaming would eat into their digital download and CD sales and that the compensation from streaming services wasn’t sufficient. One of the leading services, Spotify, reports that on average, each stream is worth about $0.007.24 Depending on the popularity of the song, that could add up to a little or a lot of money. For example, Spotify reports that similar to Apple’s iTunes, it pays out about 70 percent of its revenue to music rights holders (divided between the label, performers, and songwriters) and retains about 30 percent for itself. Spotify provided examples of what typical payouts might be for a range of albums in a single month (see Figure 4.3). For contrast, contemporary cellist Zoë Keating, an independent recording artist, reported that she earned just $808 in the first half of 2013 from 201,412 Spotify streams of two of her older recordings distributed by CD Baby.25

Songs played on Internet radio, like Pandora, Slacker, or iHeartRadio, have yet another formula for determining royalties. In 2000, the nonprofit group SoundExchange was established to collect royalties for Internet radio. (The significant difference between Internet radio and subscription streaming services is that on Internet radio, listeners can’t select specific songs to play. Instead, Internet stations have “theme” stations.) SoundExchange charges fees of $0.002 per play, per listener. Large Internet radio stations can pay up to 25 percent of their gross revenue (less for smaller Internet radio stations, and a small flat fee for streaming nonprofit stations). About 50 percent of the fees go to the music label, 45 percent go to the featured artists, and 5 percent go to nonfeatured artists.

Finally, video services like YouTube and Vevo have become sites to generate advertising revenue through music videos, which can attract tens of millions of views (see “Case Study: Psy and the Meaning of ‘Gangnam Style’” on page 142). For example, Beyoncé’s 2014 video for “Drunk in Love” drew more than 166 million views in just five months. Even popular amateur videos that use copyrighted music can create substantial revenue for music labels and artists. The 2009 amateur video “JK Wedding Entrance Dance” (reprised in a wedding scene in TV’s The Office) has about 87 million views. Instead of asking YouTube to remove the wedding video for its unauthorized use of Chris Brown’s song “Forever,” Sony licensed the video to stay on YouTube. At the rate of $1 per thousand video plays, it ultimately generated about $87,000 in ad revenue.

MY MORNING JACKET

Though fewer rock bands have found enormous success following the digital turn, this classic-

There aren’t standard formulas for sharing ad revenue from music videos, but there is movement in that direction. In 2012, Universal Music Group and the National Music Publishers’ Association agreed that music publishers would be paid 15 percent of advertising revenues generated by music videos licensed for use on YouTube and Vevo.

CASE STUDY

Psy and the Meaning of “Gangnam Style”

by Michael Park

South Korean musician Psy (aka Park Jae-

Although Psy’s crossover appeal is largely unprecedented, his overwhelming popularity has many Koreans both gratified and puzzled.1 The K-

On one hand, it is possible to conclude that Psy’s crossover success represents greater social acceptance of Asian men who have historically been absent or marginalized in mainstream media representations. However, Psy and his physicality in the video also evoke one of the stereotyped roles that mainstream media has situated Asian men in: the emasculated and clownish Asian male. The celebratory reception of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” indicates that in order for Asian males to find popular appeal in the audiovisual realm, they too must negotiate with a “codified visual hierarchy” where consumers will only accept caricatured images of Asian men.

On The Ellen DeGeneres Show, it becomes clear that Psy’s value as a guest is centered on his comical dance; he is relegated to an object of humor who elicits laughs with his minstrel performance. Psy teaches Britney Spears and Ellen his horse dance before performing the song for the audience. Ellen fails to properly introduce Psy, and the audience and viewers learn nothing about him, nor are the song’s lyrics or subversive message inquired about. On Saturday Night Live, Psy’s comical horse dance and minstrelsy are further exploited in a sketch featuring host Seth MacFarlane. The point is clear: the comical dance moves and wacky visuals are consumed as silly entertainment and comic relief. Psy never speaks a word except for “Oppa Gangnam Style.” Like his debut on Ellen, Psy stands as a recognizable prop, eager to entertain with his comical physicality. On Chelsea Lately, Psy makes an appearance in a bit that has him galloping his signature horse dance while performing menial office tasks, such as stomping on cardboard boxes, dusting office portraits, and stapling papers. Throughout the skit, he never speaks; he never even blurts out “Gangnam Style” while performing his dance.

Psy’s “crossover success” into America’s mainstream cultural imaginary, coupled with the absence of prototypical male K-

Source: Adapted from Michael Park, “Psy-

Ozan Kose/AFP/Getty Images

Alternative Voices

JUSTIN BIEBER began posting videos of himself singing on YouTube when he was only twelve. By the time he was fifteen, his YouTube channel had over a million views and he caught the attention of a music executive. Signed to a major label (Island Records) in 2008, Bieber is now a certified sensation, with multiple hit songs and legions of teenage female fans, who have caused at least three stampedes at various appearances. ChinaFotoPress/ChinaFotoPress via Getty Images

A vast network of independent (indie) labels, distributors, stores, publications, and Internet sites devoted to music outside of the major label system has existed since the early days of rock and roll. The indie industry nonetheless continues to thrive, providing music fans access to all styles of music, including some of the world’s most respected artists.

Independent labels have become even more viable by using the Internet as a low-

LaunchPad

Streaming Music Videos

On LaunchPad for Media & Culture, watch a clip of recent music videos from Katy Perry.

Discussion: Music videos get less TV exposure than they did in their heyday, but they can still be a crucial part of major artists’ careers. How do these videos help sell Perry’s music?

Some established rock acts, like Nine Inch Nails and Amanda Palmer, are taking another approach to their business model, shunning major labels and independents and using the Internet to directly reach their fans. By selling music online at their own Web sites or selling CDs at live concerts, music acts generally do better, cutting out the retailer and keeping more of the revenue themselves. Artists and bands can also build online communities around their Web sites, listing shows, news, tours, photos, and downloadable songs. Social networking sites are another place for fans and music artists to connect. MySpace was one of the first dominant sites, but Facebook eventually eclipsed it as the go-