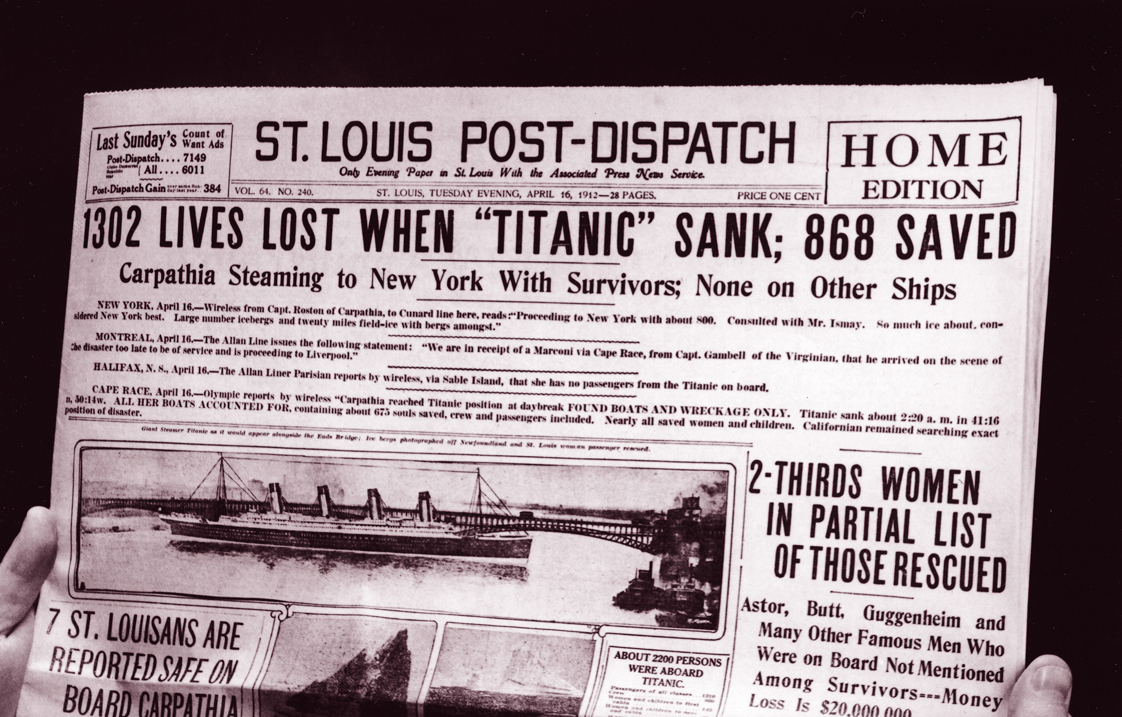

Early Technology and the Development of Radio

A TELEGRAPH OPERATOR reads the perforated tape. Sending messages using Morse code across telegraph wires was the precursor to radio, which did not fully become a mass medium until the 1920s. SSPL/Getty Images

Radio did not emerge as a full-

Although it was a revolutionary technology, the telegraph had its limitations. For instance, while it dispatched complicated language codes, it was unable to transmit the human voice. Moreover, ships at sea still had no contact with the rest of the world. As a result, navies could not find out that wars had ceased on land and often continued fighting for months. Commercial shipping interests also lacked an efficient way to coordinate and relay information from land and between ships. What was needed was a telegraph without the wires.

Maxwell and Hertz Discover Radio Waves

The key development in wireless transmissions came from James Maxwell, a Scottish physicist who in the mid-

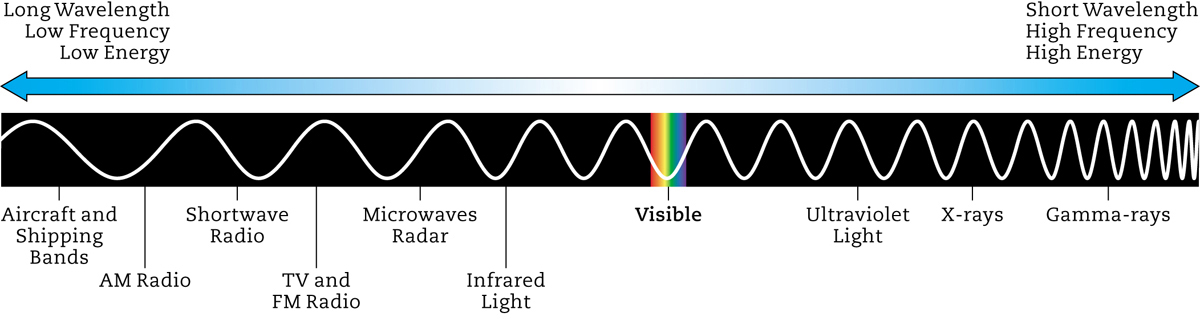

FIGURE 5.1 THE ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUM Data from: NASA, http:/

It was German physicist Heinrich Hertz, however, who in the 1880s proved Maxwell’s theories. Hertz created a crude device that permitted an electrical spark to leap across a small gap between two steel balls. As the electricity jumped the gap, it emitted waves; this was the first recorded transmission and reception of an electromagnetic wave. Hertz’s experiments significantly advanced the development of wireless communication.

Marconi and the Inventors of Wireless Telegraphy

In 1894, Guglielmo Marconi—

Popular Radio and the Origins of Broadcasting Mark Davis/Getty Images (top); Courtesy RadioTunes.com (bottom)

In 1896, Marconi traveled to England, where he received a patent on wireless telegraphy, a form of voiceless point-

History often cites Marconi as the “father of radio,” but another inventor unknown to him was making parallel discoveries about wireless telegraphy in Russia. Alexander Popov, a professor of physics in St. Petersburg, was also experimenting with sending wireless messages over distances. Popov announced to the Russian Physicist Society of St. Petersburg on May 7, 1895, that he had transmitted and received signals over a distance of six hundred yards.2 Yet Popov was an academic, not an entrepreneur, and after Marconi accomplished a similar feat that same summer, Marconi was the first to apply for and receive a patent. However, May 7 is celebrated as Radio Day in Russia.

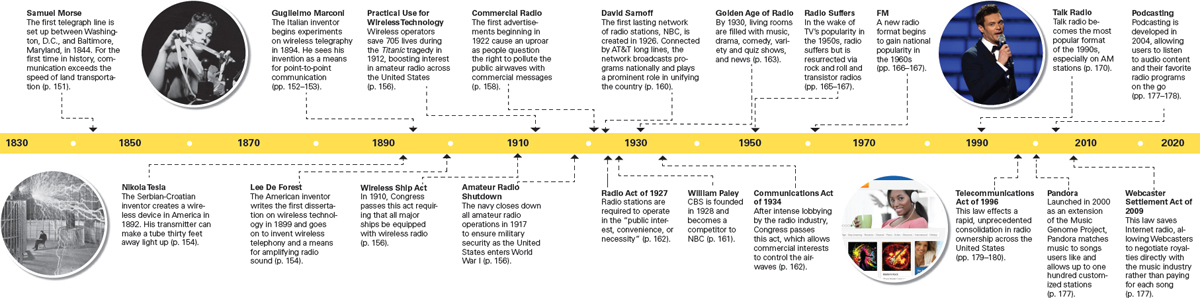

It is important to note that the work of Popov and Marconi was preceded by that of Nikola Tesla, a Serbian-

Wireless Telephony: De Forest and Fessenden

In 1899, inventor Lee De Forest (who, in defiance of other inventors, liked to call himself the “father of radio”) wrote the first Ph.D. dissertation on wireless technology, building on others’ innovations. In 1901, De Forest challenged Marconi, who was covering New York’s International Yacht Races for the Associated Press, by signing up to report the races for a rival news service. The competing transmitters jammed each other’s signals so badly, however, that officials ended up relaying information on the races in the traditional way—

In 1902, De Forest set up the Wireless Telephone Company to compete head-

De Forest’s biggest breakthrough was the development of the Audion, or triode, vacuum tube, which detected radio signals and then amplified them. De Forest’s improvements greatly increased listeners’ ability to hear dots and dashes and, later, speech and music on a receiver set. His modifications were essential to the development of voice transmission, long-

NIKOLA TESLA

A double-

The credit for the first voice broadcast belongs to Canadian engineer Reginald Fessenden, formerly a chief chemist for Thomas Edison. Fessenden went to work for the U.S. Navy and eventually for General Electric (GE), where he played a central role in improving wireless signals. Both the navy and GE were interested in the potential for voice transmissions. On Christmas Eve in 1906, after GE built Fessenden a powerful transmitter, he gave his first public demonstration, sending a voice through the airwaves from his station at Brant Rock, Massachusetts. A radio historian describes what happened:

That night, ship operators and amateurs around Brant Rock heard the results: “someone speaking! . . . a woman’s voice rose in song. . . . Next someone was heard reading a poem.” Fessenden himself played “O Holy Night” on his violin. Though the fidelity was not all that it might be, listeners were captivated by the voices and notes they heard. No more would sounds be restricted to mere dots and dashes of the Morse code.6

Ship operators were astonished to hear voices rather than the familiar Morse code. (Some operators actually thought they were having a supernatural encounter.) This event showed that the wireless medium was moving from a point-

In 1910, De Forest transmitted a performance of Tosca by the Metropolitan Opera to friends in the New York area with wireless receivers. At this point in time, radio passed from the novelty stage to the entrepreneurial stage, during which various practical uses would be tested before radio would launch as a mass medium.

Regulating a New Medium

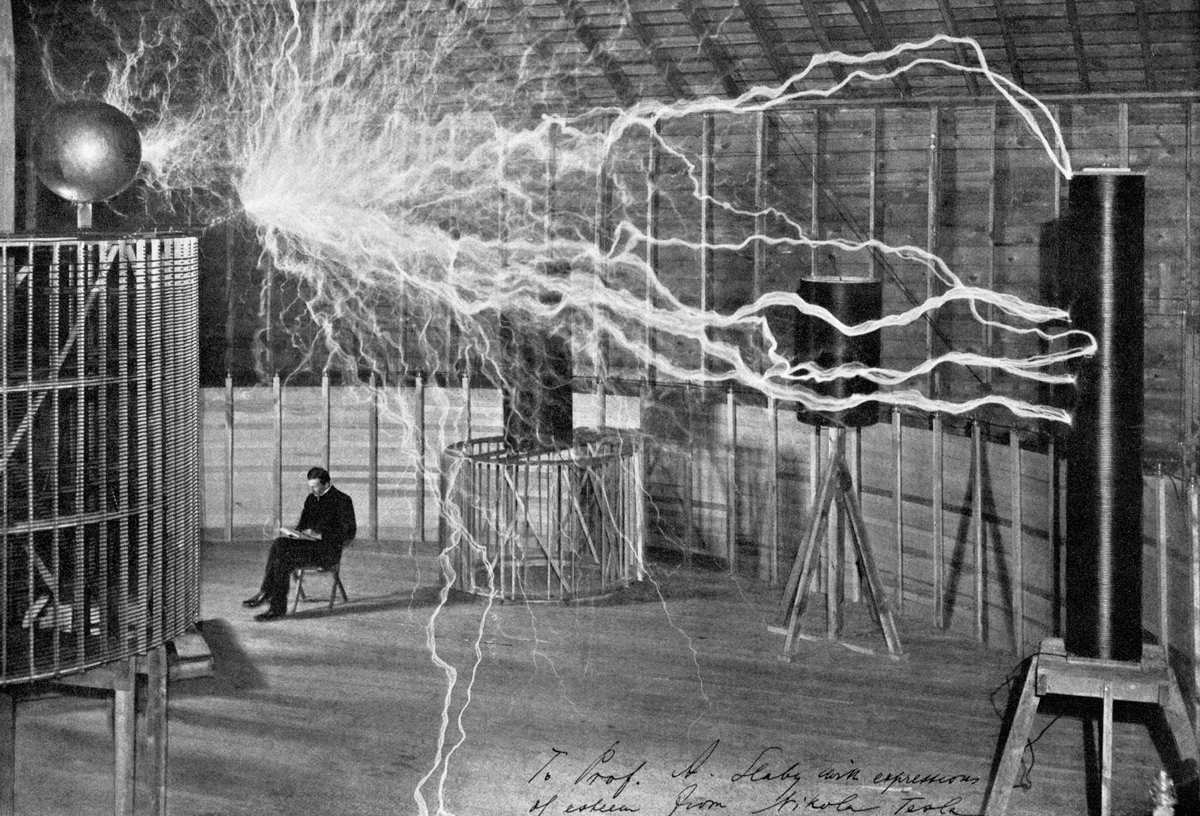

NEWS OF THE TITANIC

Despite the headline in the St. Louis Post-

The two most important international issues affecting radio in the first decade of the twentieth century were ship radio requirements and signal interference. Congress passed the Wireless Ship Act in 1910, which required that all major U.S. seagoing ships carrying more than fifty passengers and traveling more than two hundred miles off the coast be equipped with wireless equipment with a one-

Radio Waves as a Natural Resource

In the wake of the Titanic tragedy, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912, which addressed the problem of amateur radio operators increasingly cramming the airwaves. Because radio waves crossed state and national borders, legislators determined that broadcasting constituted a “natural resource”—a kind of interstate commerce. This meant that radio waves could not be owned; they were the collective property of all Americans, just like national parks. Therefore, transmitting on radio waves would require licensing in the same way that driving a car requires a license.

A short policy guide, the first Radio Act required all wireless stations to obtain radio licenses from the Commerce Department. This act, which governed radio until 1927, also formally adopted the SOS Morse-

The Impact of World War I

By 1915, more than twenty American companies sold wireless point-

As wireless telegraphy played an increasingly large role in military operations, the navy sought tight controls on information. When the United States entered the war in 1917, the navy closed down all amateur radio operations and took control of key radio transmitters to ensure military security. As the war was nearing its end in 1919, British Marconi placed an order with GE for twenty-

Roosevelt was guided in turn by President Woodrow Wilson’s goal of developing the United States as an international power, a position greatly enhanced by American military successes during the war. Wilson and the navy saw an opportunity to slow Britain’s influence over communication and to promote a U.S. plan for the control of the emerging wireless operations. Thus corporate heads and government leaders conspired to make sure radio communication would serve American interests.

The Formation of RCA

Some members of Congress and the corporate community opposed federal legislation that would grant the government or the navy a radio monopoly. Consequently, GE developed a compromise plan that would create a private sector monopoly—that is, a private company that would have the government’s approval to dominate the radio industry. First, GE broke off negotiations to sell key radio technologies to European-

Under RCA’s patent pool arrangement, wireless patents from the navy, AT&T, GE, the former American Marconi, and other companies were combined to ensure U.S. control over the manufacture of radio transmitters and receivers. Initially AT&T, then the government-

A government restriction at the time mandated that no more than 20 percent of RCA could be owned by foreigners. This restriction, later raised to 25 percent, became law in 1927 and applied to all U.S. broadcasting stocks and facilities. Because of this rule, Rupert Murdoch—

RCA’s most significant impact was that it gave the United States almost total control over the emerging mass medium of broadcasting. At the time, the United States was the only country that placed broadcasting under the care of commercial, rather than military or government, interests. By pooling more than two thousand patents and sharing research developments, RCA ensured the global dominance of the United States in mass communication, a position it maintained in electronic hardware into the 1960s and maintains in program content today.