The Economics of Broadcast Radio

Radio continues to be one of the most used mass media, reaching about 92 percent of American teenagers and adults every week.16 Because of radio’s broad reach, the airwaves are very desirable real estate for advertisers, who want to reach people in and out of their homes; for record labels, who want their songs played; and for radio station owners, who want to create large radio groups to dominate multiple markets.

Local and National Advertising

About 10 percent of all U.S. spending on media advertising goes to radio stations. Like newspapers, radio generates its largest profits by selling local and regional ads. Thirty-

When radio stations want to purchase programming, they often turn to national network radio, which generates more than $1 billion in ad sales annually by offering dozens of specialized services. For example, Westwood One, the nation’s largest radio network service, managed by Cumulus Media, reaches more than 225 million consumers a week with a range of programming, including regular network radio news (e.g., ABC, CBS, and NBC), entertainment programs (e.g., The Bob & Tom Show), talk shows (e.g., The Mark Levin Show), and complete twenty-

Manipulating Playlists with Payola

Radio’s impact on music industry profits—

Despite congressional hearings and new regulations, payola persisted. Record promoters showered their favors on a few influential, high-

More recently, in 2007 four of the largest broadcasting companies—

Radio Ownership: From Diversity to Consolidation

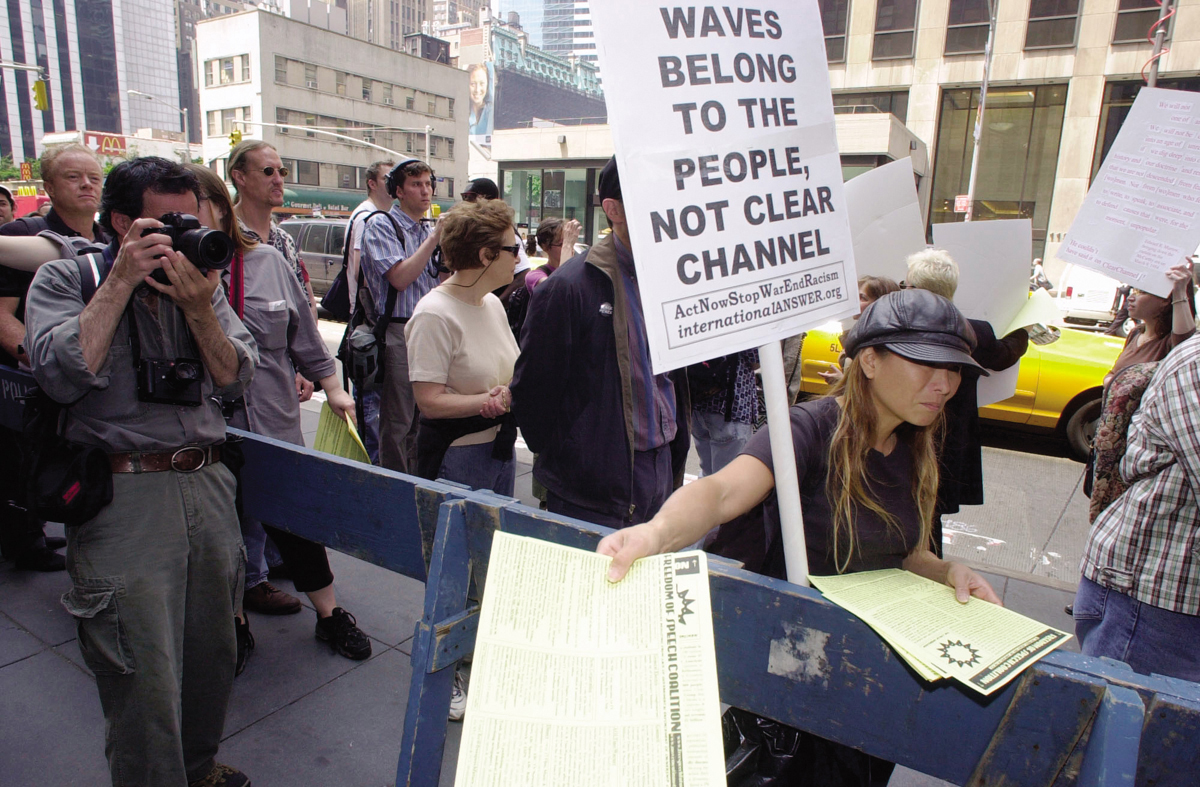

CLEAR CHANNEL COMMUNICATIONS has been a target for protesters who object to the company’s media dominance, allowed by FCC deregulation. Clear Channel has shed some stations in recent years, but as a result of an economic downturn rather than increased regulation. The company changed its name to iHeartMedia in 2014 to reflect its future in streaming digital radio. Richard B. Levine/Newscom

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 substantially changed the rules concerning ownership of the public airwaves because the FCC eliminated most ownership restrictions on radio. As a result, 2,100 stations and $15 billion changed hands that year alone. From 1995 to 2005, the number of radio station owners declined by one-

Once upon a time, the FCC tried to encourage diversity in broadcast ownership. From the 1950s through the 1980s, a media company could not own more than seven AM, seven FM, and seven TV stations nationally, and could own only one radio station per market. Just prior to the 1996 act, the ownership rules were relaxed to allow any single person or company to own up to twenty AM, twenty FM, and twelve TV stations nationwide, but only two in the same market.

The 1996 act allows individuals and companies to acquire as many radio stations as they want, with relaxed restrictions on the number of stations a single broadcaster may own in the same city: The larger the market or area, the more stations a company may own within that market. For example, in areas where forty-

With few exceptions, for the past two decades the FCC has embraced the consolidation schemes pushed by the powerful National Association of Broadcasters lobbyists in Washington, D.C., under which fewer and fewer owners control more and more of the airwaves.

The consequences of the 1996 Telecommunications Act and other deregulation have been significant. Consider the cases of Clear Channel Communications (now iHeartMedia) and Cumulus, the two largest radio chain owners in terms of number of stations owned (see Table 5.3). Clear Channel Communications was formed in 1972 with one San Antonio station. In 1998, it swallowed up Jacor Communications, the fifth-

| Rank | Company | Number of Stations |

| 1 | iHeartMedia (Top property: WLTW- |

840 |

| 2 | Cumulus (KNBR- |

525 |

| 3 | Townsquare Media (KSAS- |

312 |

| 4 | Educational Media Foundation (KLVB, Citrus Heights, Calif.) | 289 |

| 5 | American Family Association (WAFR, Tupelo, Miss.) | 193 |

| 6 | CBS Radio (KROQ- |

126 |

| 7 | Entercom (WEEI- |

103 |

| 8 | Salem Communications (KLTY, Dallas– |

95 |

| 9 | Saga Communications (WSNY, Columbus, Ohio) | 92 |

| 10 | Univision (KLVE- |

68 |

| 11 | Midwest Communications (WTAQ- |

62 |

| 12 | Cox (WSB- |

57 |

Table 5.3: TABLE 5.3 TOP TWELVE RADIO COMPANIES (BY NUMBER OF STATIONS), 2014 Data from: The 10-

Townsquare Media, launched in 2010 with the buyout of a 62-

Combined, the top three commercial groups—

A smaller radio conglomerate, but one that is perhaps the most dominant in a single format area, is Univision. With a $3 billion takeover of Hispanic Broadcasting in 2003, Univision is the top Spanish-

Alternative Voices

ALTERNATIVE RADIO VOICES can also be found on college stations, typically started by students and community members. There are around 520 such stations currently active in the United States, broadcasting in an eclectic variety of formats. As rock radio influence has declined, college radio has become a major outlet for new indie bands. © Thomas Fricke/Corbis

As large corporations gained control of America’s radio airwaves, activists in hundreds of communities across the United States protested in the 1990s by starting up their own noncommercial “pirate” radio stations capable of broadcasting over a few miles with low-

The major complaint of pirate radio station operators was that the FCC had long ago ceased licensing low-

LPFM stations are located in unused frequencies on the FM dial. Still, the NAB and National Public Radio fought to delay and limit the number of LPFM stations, arguing that such stations would cause interference with existing full-