Television, Cable, and Democracy

In the 1950s, television’s arrival significantly changed the media landscape—

The development of cable, VCRs and DVD players, DVRs, the Internet, and smartphone services has fragmented television’s audience by appealing to viewers’ individual and special needs. These changes and services, by providing more specialized and individual choices, also alter television’s role as a national unifying cultural force, potentially de-

The bottom line is that television, despite the audience fragmentation, still provides a gathering place for friends and family at the same time that it provides anywhere access to a favorite show. Like all media forms before it, television is adapting to changing technology and shifting economics. As the technology becomes more portable and personal, TV-

TV AND DEMOCRACY

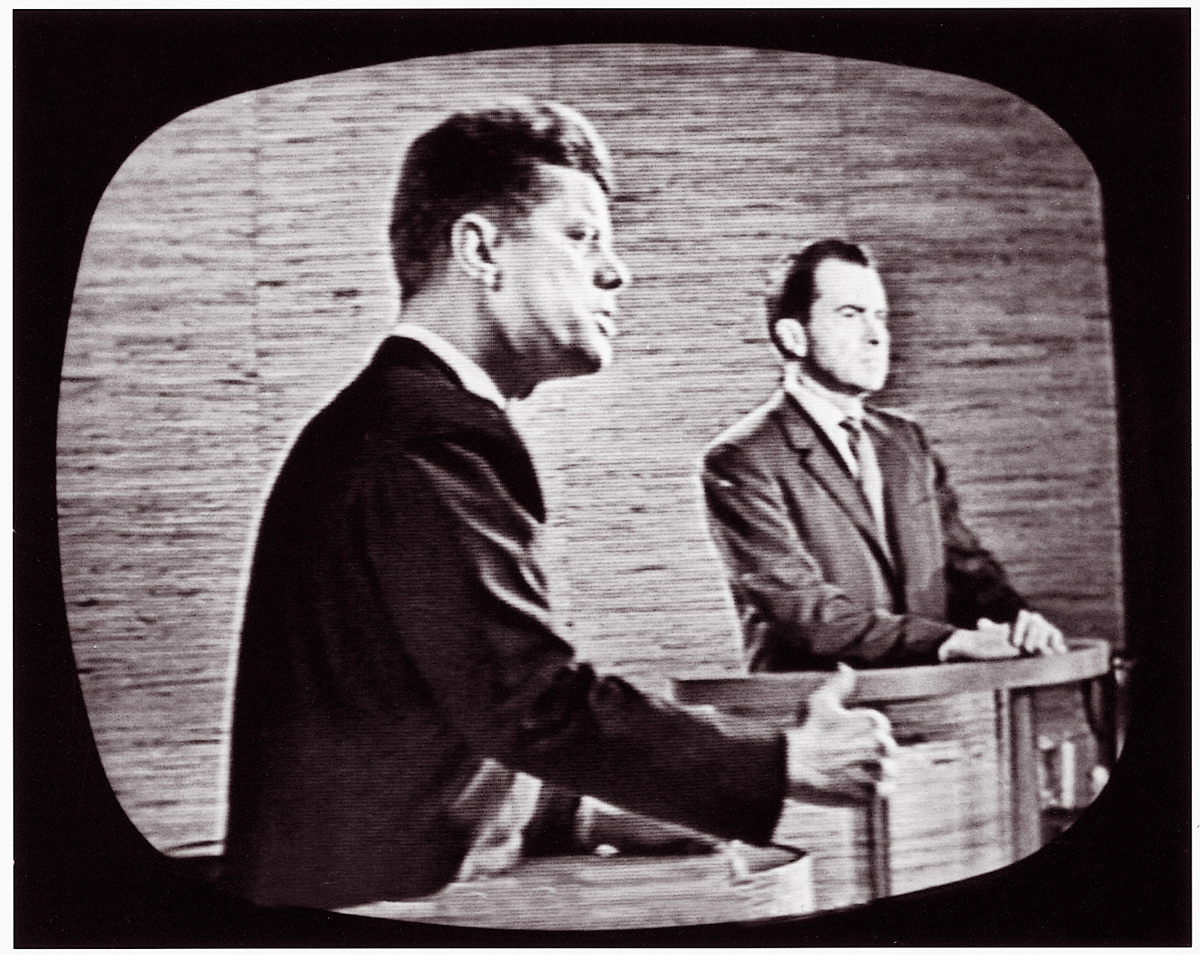

The first televised presidential debates took place in 1960, pitting Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy against Vice President Richard Nixon. Don Hewitt, who later created the long-

TV’s future will be about serving smaller rather than larger audiences. As sites like YouTube develop original programming and as niche cable services like the Weather Channel produce reality TV series about storms, no audience seems too small and no subject matter too narrow for today’s TV world. For example, by 2013, Duck Dynasty—a program about an eccentric Louisiana family that got rich making products for duck hunters—