The Origins and Development of Television

In 1948, only 1 percent of America’s households had a TV set; by 1953, more than 50 percent had one; and since the early 1960s, more than 90 percent of all homes have TV. Television’s rise throughout the 1950s created fears that radio—

Three major historical developments in television’s early years helped shape it: (1) technological innovations and patent wars, (2) the wresting of content control from advertisers, and (3) the sociocultural impact of the infamous quiz-

Early Innovations in TV Technology

In its novelty stage, television’s earliest pioneers were trying to isolate TV waves from the electromagnetic spectrum (as radio’s pioneers had done with radio waves). The big question was, If a person could transmit audio signals from one place to another, why not visual images as well? Inventors from a number of nations toyed with the idea of sending “tele-

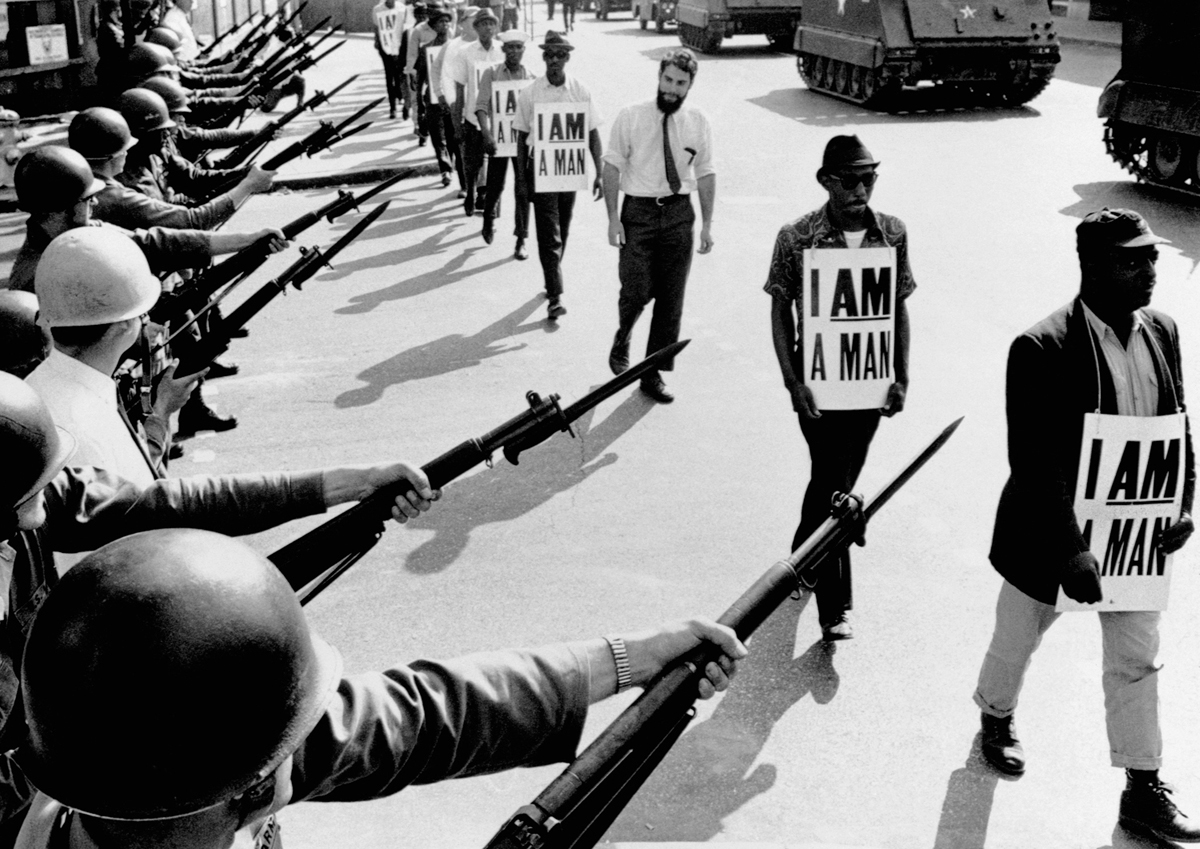

CIVIL RIGHTS

In the 1950s and 1960s, television images of Civil Rights struggles visually documented the inequalities faced by black citizens. Seeing these images made the events and struggles more “real” to a nation of viewers and helped garner support for the movement. © Bettmann/Corbis

From roughly 1897 to 1907, the development by several inventors of the cathode ray tube, the forerunner of the TV picture tube, combined principles of the camera and electricity. Because television images could not physically float through the air, technicians and inventors developed a method of encoding them at a transmission point (TV station) and decoding them at a reception point (TV set). In the 1880s, German inventor Paul Nipkow developed the scanning disk, a large flat metal disk with a series of small perforations organized in a spiral pattern. As the disk rotated, it separated pictures into pinpoints of light that could be transmitted as a series of electronic lines. As the disk spun, each small hole scanned one line of a scene to be televised. For years, Nipkow’s mechanical disk served as the foundation for experiments on the transmission of visual images.

Electronic Technology: Zworykin and Farnsworth

The story of television’s invention included a complex patents battle between two independent inventors: Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth. It began in Russia in 1907, when physicist Boris Rosing improved Nipkow’s mechanical scanning device. Rosing’s lab assistant, Vladimir Zworykin, left Russia for America in 1919 and went to work for Westinghouse and then RCA. In 1923, Zworykin invented the iconoscope, the first TV camera tube to convert light rays into electrical signals, and he received a patent for it in 1928.

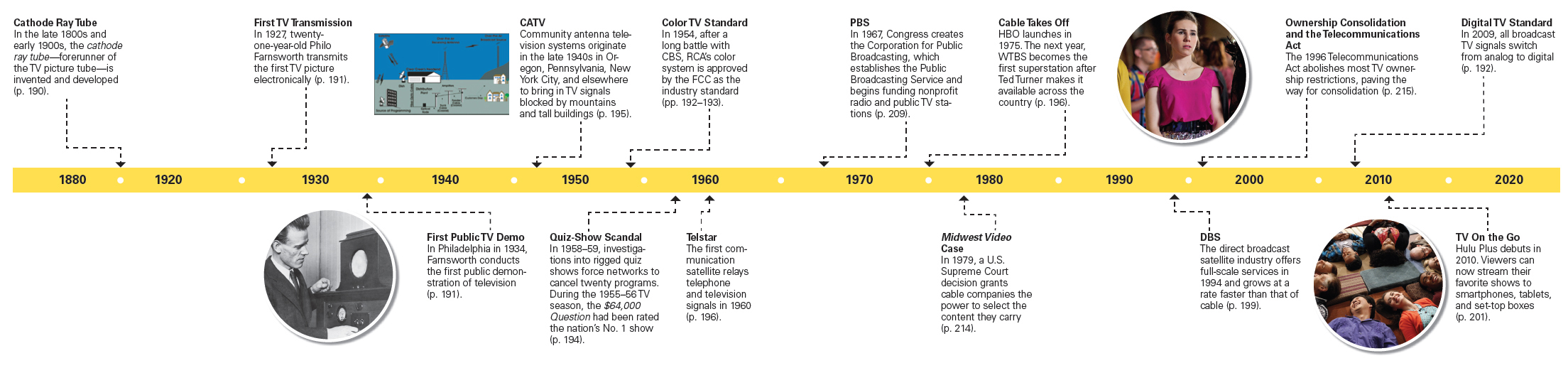

Television and Cable: The Power of Visual Culture © Bettmann/Corbis (bottom left); Jojo Whilden/© HBO/Everett Collection (top right); © NBC/Photofest (bottom right)

Around the same time, Idaho teenager Philo Farnsworth also figured out that a mechanical scanning system would not send pictures through the air over long distances. On September 7, 1927, the twenty-

After the company’s court defeat, RCA’s president, David Sarnoff, had to negotiate to use Farnsworth’s patents. Farnsworth later licensed these patents to RCA and AT&T for use in the commercial development of television. At the end of television’s development stage, Farnsworth conducted the first public demonstration of television at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia in 1934—

Setting Technical Standards

Figuring out how to push TV as a business and elevate it to a mass medium meant creating a coherent set of technical standards for product manufacturers. In the late 1930s, the National Television Systems Committee (NTSC), a group representing major electronics firms, began outlining industry-

PHILO FARNSWORTH, one of the inventors of television, experiments with an early version of an electronic TV set. © Bettmann/Corbis

The United States continued to use analog signals until 2009, when they were replaced by digital signals. These translate TV images and sounds into binary codes (ones and zeros like computers use) and allow for increased channel capacity and improved image quality and sound. HDTV, or high-

Assigning Frequencies and Freezing TV Licenses

In the early days of television, the number of TV stations a city or market could support was limited because airwave spectrum frequencies interfered with one another. Thus a market could have a channel 2 and a channel 4 but not a channel 3. Cable systems “fixed” this problem by sending channels through cable wires that don’t interfere with one another. Today, a frequency that once carried one analog TV signal can carry eight or nine compressed digital channels.

In the 1940s, the FCC began assigning channels in specific geographic areas to make sure there was no interference. As a result, for years New Jersey had no TV stations because those signals would have interfered with the New York stations. But by 1948 the FCC had issued nearly one hundred TV licenses, and there was growing concern about the finite number of channels and the frequency-

During this time, cities such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles had several TV stations, while other areas—

After a second NTSC conference in 1952 sorted out the technical problems, the FCC ended the licensing freeze, and almost thirteen hundred communities received TV channel allocations. By the mid-

The Introduction of Color Television

In 1952, the FCC tentatively approved an experimental CBS color system. However, because black-

Controlling Content—

By the early 1960s, television had become a dominant mass medium and cultural force, with more than 90 percent of U.S. households owning at least one set. Television’s new standing came as its programs moved away from the influence of radio and established a separate identity. Two important contributors to this identity were a major change in the sponsorship structure of television programming and, more significant, a major scandal.

Program Format Changes Inhibit Sponsorship

Like radio in the 1930s and 1940s, early TV programs were often developed, produced, and supported by a single sponsor. Many of the top-

David Sarnoff, then head of RCA-

In addition, the introduction of two new types of programs—

The television spectacular is today recognized by a more modest term, the television special. At NBC, Weaver bought the rights to special programs, like the Broadway production of Peter Pan, and sold spot ads to multiple sponsors. The 1955 TV version of Peter Pan was a particular success, with sixty-

THE TODAY SHOW, the first magazine-

The Rise and Fall of Quiz Shows

In 1955, CBS aired the $64,000 Question, reviving radio’s quiz-

Compared with dramas and sitcoms, quiz shows were (and are) cheap to produce, with inexpensive sets and mostly nonactors as guests. The problem was that most of these shows were rigged. To heighten the drama, key contestants were rehearsed and given the answers.

The most notorious rigging occurred on Twenty-

Quiz-

The impact of the quiz-

TWENTY-

In 1957, the most popular contestant on the quiz show Twenty-

The third, and most important, impact of the quiz-

After the scandal, quiz shows were kept out of network prime time for forty years. Finally, in 1999, ABC gambled that the nation was ready once again for a quiz show in prime time. The network had great, if brief, success with Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, which hit No. 1 that year.