The Economics of the Movie Business

Despite the development of network and cable television, video-

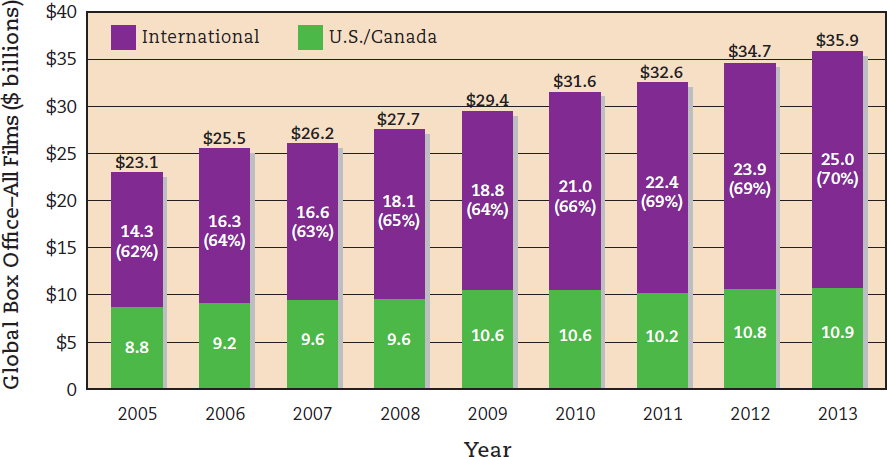

FIGURE 7.1 NORTH AMERICAN AND GLOBAL BOX-

The growing global market for Hollywood films has helped cushion the industry as the home video market undergoes a significant transformation, with the demise of the video rental business and the rise of video streaming. In order to flourish, the movie industry has had to continually revamp its production, distribution, and exhibition system and consolidate its ownership.

Production, Distribution, and Exhibition Today

In the 1970s, attendance by young moviegoers at new suburban multiplex theaters made megahits of The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1973), Jaws (1975), Rocky (1976), and Star Wars (1977). During this period, Jaws and Star Wars became the first movies to gross more than $100 million at the U.S. box office in a single year. In trying to copy the success of these blockbuster hits, the major studios set in place economic strategies for future decades. (See “Media Literacy and the Critical Process: The Blockbuster Mentality” on page 259.)

Making Money on Movies Today

With 80 to 90 percent of newly released movies failing to make money at the domestic box office, studios need a couple of major hits each year to offset losses on other films. (See Table 7.2 on page 256 for a list of the highest-

| Rank | Title/Date | Domestic Gross ** ($ millions) |

| 1 | Avatar (2009) | 760.5 |

| 2 |

Titanic (1997, 2012 3- |

658.6 |

| 3 | The Avengers (2012) | 623.4 |

| 4 | The Dark Knight (2008) | 533 |

| 5 |

Star Wars:Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999, 2012 3- |

474.5 |

| 6 | Star Wars (1977, 1997) | 461 |

| 7 | The Dark Knight Rises (2012) | 447.8 |

| 8 | Shrek2 (2004) | 437.7 |

| 9 |

E.T.: The Extra- |

435 |

| 10 | The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013) | 424.7 |

Table 7.1: TABLE 7.2 THE TOP 10 ALL-

With climbing film costs, creating revenue from a movie is a formidable task. Studios make money on movies from six major sources:

- First, the studios get a portion of the theater box-

office revenue— about 40 percent of the box- office take (the theaters get the rest). More recently, studios have found that they can often reel in bigger box- office receipts for 3- D films and their higher ticket prices. For example, admission to the 2- D version of a film costs $15 at a New York City multiplex, while the 3- D version costs $19.50 at the same theater. In 2013, 3- D film screenings accounted for 16 percent of domestic box- office revenue. As Hollywood makes more 3- D films (the latest form of product differentiation), the challenge for major studios has been to increase the number of digital 3- D screens across the country. By 2013, about 37 percent of U.S. theater screens were capable of showing digital 3- D. - Second, about three to four months after the theatrical release comes the home video market, which includes video-

on- demand (VOD), subscription streaming, and the remaining Blu- ray and DVD sales and rental business. This release “window” generates more revenue than the domestic box- office income for major studios, but has been in transition as VOD has replaced the Blu- ray and DVD formats. Video- on- demand includes services like iTunes, Amazon, Google Play, Vudu, Hulu Plus, Netflix, and the VOD services of cable companies like Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Cox, Verizon, and satellite providers DirecTV and Dish. Depending on the agreement with the film distributer, movies may be purchased for instant viewing, rented for a limited period of time at a lower price, or (as in the case of Netflix, the largest streaming service with over 36 million subscribers) instantly streamed as part of a monthly fee for access to the company’s entire library of licensed offerings. Generally, discount rental kiosk companies like Redbox must wait twenty-

eight days after films go on sale before they can rent them. Netflix has entered into a similar agreement with movie studios in exchange for more video streaming content— a concession to Hollywood’s preference to first try to get the greater profits from selling movies as digital downloads or as DVDs before renting them or licensing them to a streaming service. Independent films and documentaries often bypass the theatrical box- office release window entirely because of the necessary steep marketing expenses and instead go straight to home video for release. An executive with the Weinstein Company, a leading independent studio, suggests that a traditional release to movie theaters makes sense only if the studio anticipates that the film will make gross revenues of more than $20 million.16 There is pressure from services like Netflix for Hollywood to release films simultaneously to the home video market and to theaters, but the theater industry and their major studio allies have fiercely protected the three- to four- month exclusive window that theaters have for movie releases, arguing that to lose exclusivity would destroy the movie theater business.17 - Third are the next “windows” of release for a film: premium cable (such as HBO and Showtime), then network and basic cable showings, and finally the syndicated TV market. The price these cable and television outlets pay to the studios is negotiated on a film-

by- film basis. - Fourth, studios earn revenue from distributing films in foreign markets. In fact, at $25 billion in 2013, international box-

office gross revenues are more than double the U.S. and Canadian box- office receipts, and they continue to climb annually, even as other countries produce more of their own films. - Fifth, studios make money by distributing the work of independent producers and filmmakers, who hire the studios to gain wider circulation. Independents pay the studios between 30 and 50 percent of the box-

office and home video money they make from movies. - Sixth, revenue is earned from merchandise licensing and product placements in movies. In the early days of television and film, characters generally used generic products, or product labels weren’t highlighted in shots. For example, Bette Davis’s and Humphrey Bogart’s cigarette packs were rarely seen in the actors’ movies. But with soaring film production costs, product placements are adding extra revenue while lending an element of authenticity to the staging. Famous product placements in movies include Reese’s Pieces in E.T. (1982), Pepsi-

Cola in Back to the Future II (1989), and an entire line of toy products in The Lego Movie (2014).

Theater Chains Consolidate Exhibition

Film exhibition is controlled by a handful of theater chains; the leading five companies operate more than 50 percent of U.S. screens. Each of the major chains—

BLOCKBUSTERS like Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), which draws on Disney’s Marvel Comics property, are sought after despite their large budgets because they can potentially bring in twice their cost in box-

The strategy of the leading theater chains during the mid-

Still, theater chains sought to be less reliant on Hollywood studios, and with new digital projectors they began to screen nonmovie events, including live sporting events, rock concerts, and classic TV show marathons. One of the most successful theater events is the live HD simulcast of the New York Metropolitan Opera’s performances, which began in 2007 and during the 2014–

The Major Studio Players

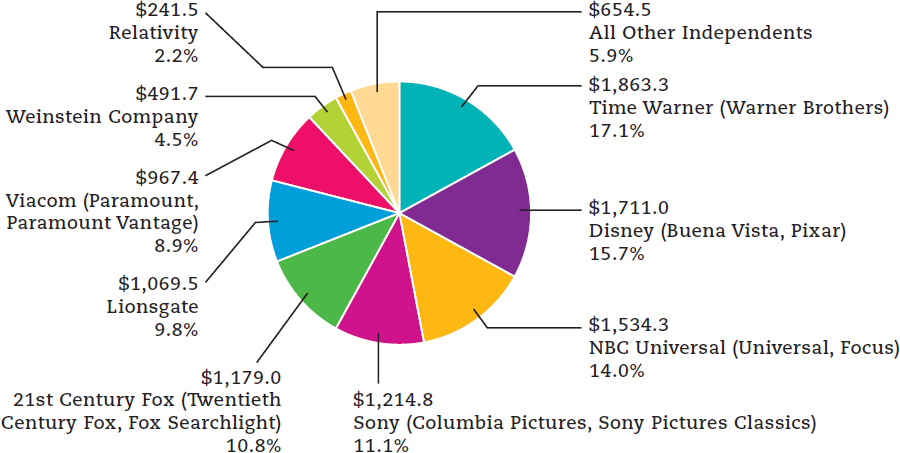

The current Hollywood commercial film business is ruled primarily by six companies: Warner Brothers, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, Universal, Columbia Pictures, and Disney—

FIGURE 7.2 MARKET SHARE OF U.S. FILM STUDIOS AND DISTRIBUTORS, 2013 (IN $ MILLIONS) Note: Based on gross box-

In the 1980s, to offset losses resulting from box-

The biggest corporate mergers have involved the internationalization of the American film business. Investment in American popular culture by the international electronics industry is particularly significant. This business strategy represents a new, high-

SYNERGIES in feature films can be easy for Disney, which is a $45 billion multinational corporation. Frozen (2013) is one of Disney’s biggest animated hits ever, and Frozen merchandise was in short supply in North America for fans wanting to celebrate the story of Anna and Elsa, two princess sisters who also became attractions at Disney resort parks. The movie’s soundtrack hit No. 1 in sales, and Disney Cruise Line and the Adventures by Disney tour company experienced a huge increase in holiday business to Geirangerfjord, Norway, the fjord that inspired the film’s fantasy kingdom of Arendelle. © Walt Disney Pictures/Everett Collection

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

The Blockbuster Mentality

In the beginning of this chapter, we noted Hollywood’s shift toward a blockbuster mentality after the success of films like Star Wars. How pervasive is this blockbuster mentality, which targets an audience of young adults, releases action-

1 DESCRIPTION. Consider a list of the all-

2 ANALYSIS. Note patterns in the list. For example, of the thirty top-

3 INTERPRETATION. What do the patterns mean? It’s clear, economically, why Hollywood likes to have successful blockbuster movie franchises. But what kinds of films get left out of the mix? Hits like Forrest Gump (now bumped out of the Top 30), which may have had big-

4 EVALUATION. It is likely that we will continue to see an increase in youth-

5 ENGAGEMENT. Watch independent and foreign films and see what you’re missing. Visit foreignfilms.com or the Sundance Film Festival site and browse through the many films listed. Find these films on Netflix, Amazon, Google Play, or iTunes (and if the films are unavailable, let these services know). Write your cable company and request to have the Sundance Channel on your cable lineup. Organize an independent film night on your college campus and bring these films to a crowd.

Convergence: Movies Adjust to the Digital Turn

The biggest challenge the movie industry faces today is the Internet. As broadband Internet service connects more households, movie fans are increasingly getting movies from the Web. After witnessing the difficulties that illegal file-

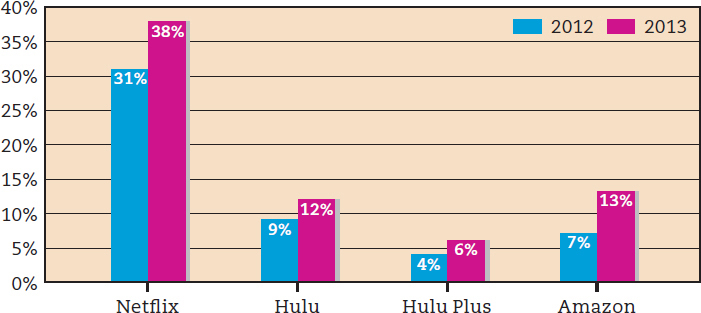

The popularity of Netflix’s streaming service opened the door to other similar services. Hulu, a joint venture by NBC Universal (Universal Studios), Twentieth Century Fox, and Disney, was created as the studios’ attempt to divert attention from YouTube and get viewers to either watch free, ad-

Movies are also increasingly available to stream or download on mobile phones and tablets. Several companies, including Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Google, Apple, Redbox, and Blockbuster, have developed distribution to mobile devices. Small screens don’t offer an optimal viewing experience, but if customers watch movies on their mobile devices, they will likely use the same company’s service to continue viewing on the larger screens of computers and televisions.

The year 2012 marked a turning point: For the first time, movie fans accessed more movies through digital online media than physical copies, like DVD and Blu-

The digital turn creates two long-

The Internet has also become an essential tool for movie marketing, and one that studios are finding less expensive than traditional methods, like television ads or billboards. Films regularly have Web pages, but many studios now also use a full menu of social media to promote films in advance of their release. For example, the marketing plan for Lionsgate’s 2012 movie The Hunger Games, which launched an enormously successful movie franchise, employed “near-

Alternative Voices

With the major studios exerting such a profound influence on the worldwide production, distribution, and exhibition of movies, new alternatives have helped open and redefine the movie industry. The digital revolution in movie production is the most recent opportunity to wrest some power away from the Hollywood studios. Substantially cheaper and more accessible than standard film equipment, digital video is a shift from celluloid film; it allows filmmakers to replace expensive and bulky 16-

FIGURE 7.3 ONLINE VIDEO STREAMING MARKET SHARE RANKING IN 2013 Data from: Nielsen Newswire, “‘Binging’ Is the New Viewing for Over-

PARANORMAL ACTIVITY (2007), the horror film made by first-

British director Mike Figgis achieved the milestone of producing the first fully digital release from a major studio with his film Timecode (2000). Though digital video has become commonplace on big studio productions, the greatest impact of digital technology has been on independent filmmakers. Low-

Because digital production puts movies in the same format as the Internet, independent filmmakers have new distribution venues beyond film festivals or the major studios. For example, Vimeo, YouTube, and Netflix have grown into leading Internet sites for the screening and distribution of short films and film festivals, providing filmmakers with their most valuable asset—