Books and the Future of Democracy

AMAZON’S WAREHOUSES go far beyond the stockrooms of a typical brick-

As we enter the digital age, the book-

Although there is an increased interest in books, many people are concerned about their quality. Indeed, the economic clout of publishing houses run by large multinational corporations has made it more difficult for new authors and new ideas to gain a foothold. Often, editors and executives prefer to invest in commercially successful authors or those who have a built-

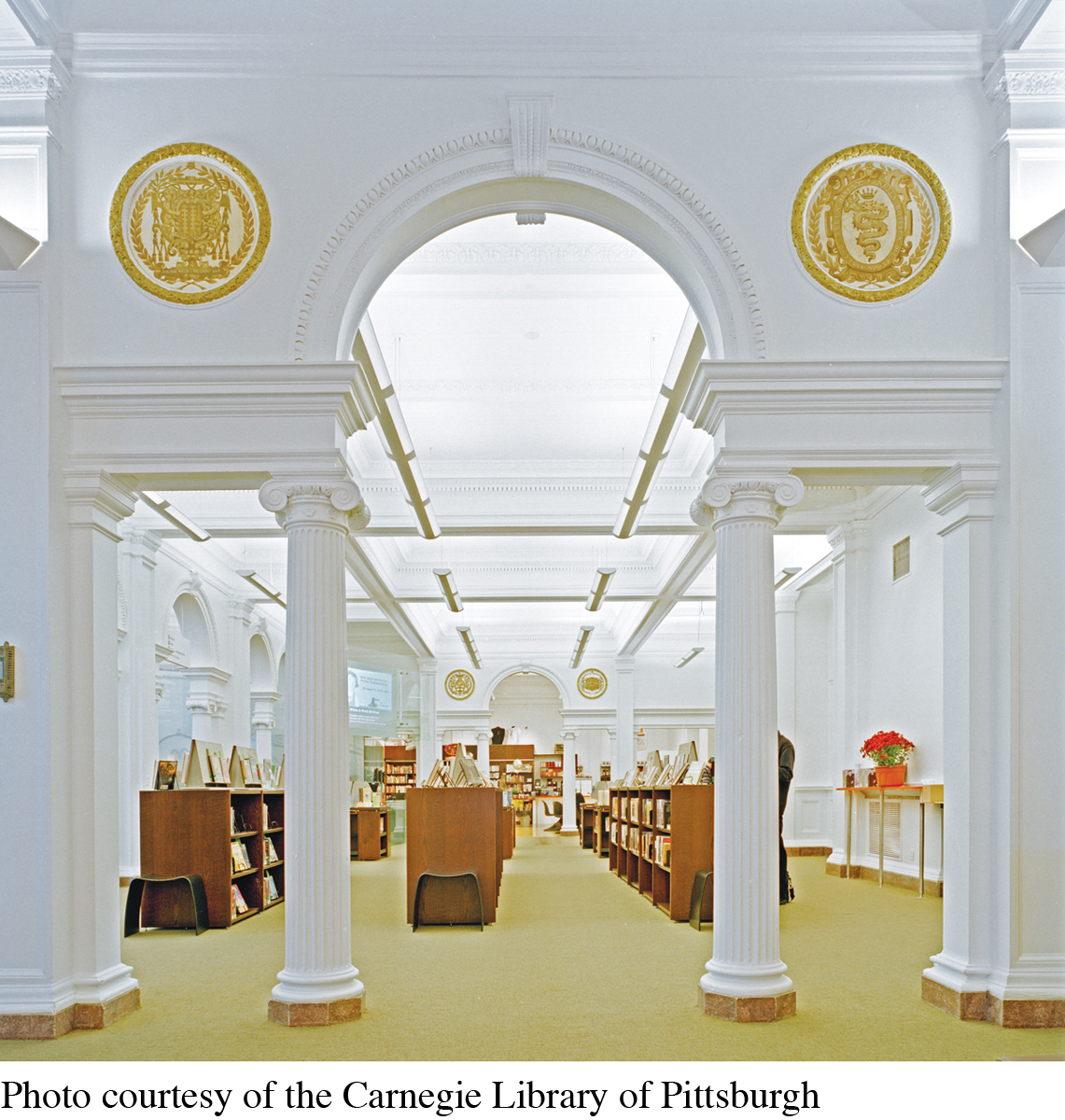

CARNEGIE LIBRARIES The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh was first opened in 1895 with a $1 million donation from Andrew Carnegie (at the time, it was called Main Library). In total, eight branches were built in Pittsburgh as Carnegie Libraries.

Yet books and reading have survived the challenge of visual and digital culture. Developments such as digital publishing, word processing, audio books, children’s pictorial literature, and online services have integrated aspects of print and electronic culture into our daily lives. Most of these new forms carry on the legacy of books, transcending borders to provide personal stories, world history, and general knowledge to all who can read.

Since the early days of the printing press, books have helped us understand ideas and customs outside our own experiences. For democracy to work well, we must read. When we examine other cultures through books, we discover not only who we are and what we value but also who others are and what our common ties might be.