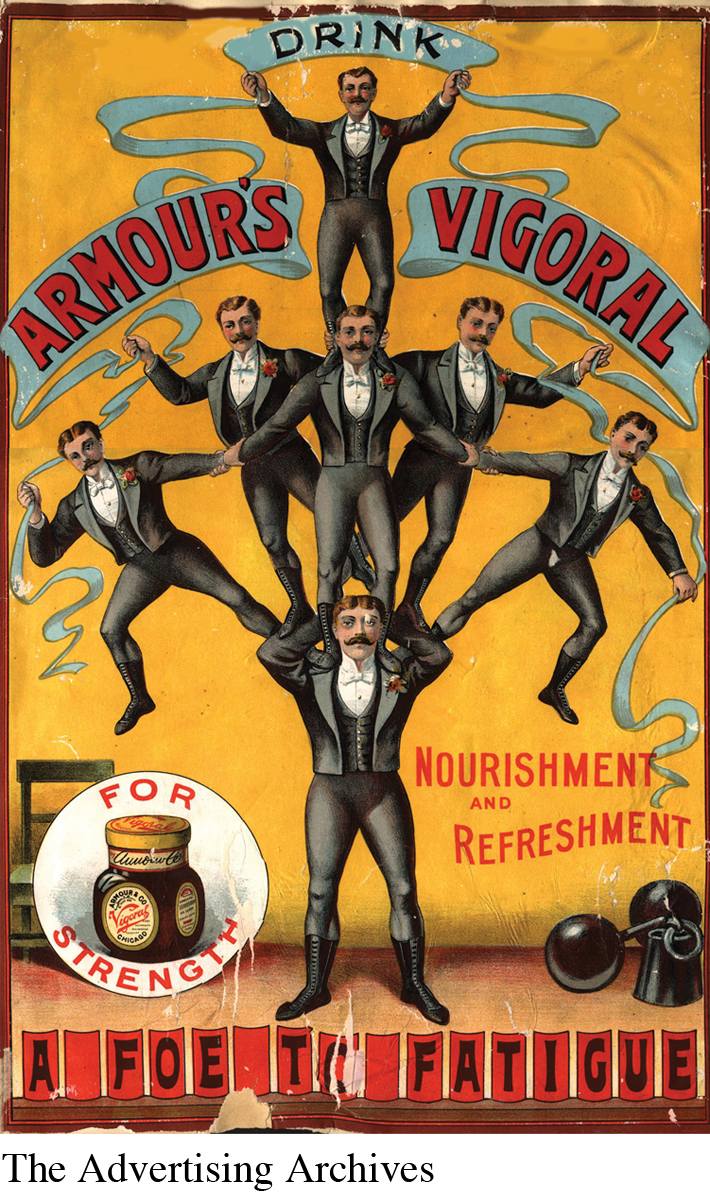

Early Developments in American Advertising

Advertising has existed since 3000 BCE, when shop owners in ancient Babylon hung outdoor signs carved in stone and wood so that customers could spot their stores. Merchants in early Egyptian society hired town criers to walk through the streets, announcing the arrival of ships and listing the goods on board. Archaeologists searching Pompeii, the ancient Italian city destroyed when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, found advertising messages painted on walls. By 900 CE, many European cities featured town criers who not only called out the news of the day but also directed customers to various stores.

Other early media ads were on handbills, posters, and broadsides (long, newsprint-

To distinguish their approach from the commercialism of newspapers, early magazines refused to carry advertisements. By the mid-

Advertising and Commercial Culture

The First Advertising Agencies

Until the 1830s, little need existed for elaborate advertising, as few goods and products were even available for sale. Before the Industrial Revolution, 90 percent of Americans lived in isolated areas and produced most of their own tools, clothes, and food. The minimal advertising that did exist usually featured local merchants selling goods and services in their own communities. In the United States, national advertising, which initially focused on patent medicines, didn’t start in earnest until the 1850s, when railroads linking the East Coast to the Mississippi River valley began carrying newspapers, handbills, and broadsides—

The first American advertising agencies were newspaper space brokers, individuals who purchased space in newspapers and sold it to various merchants. Newspapers, accustomed to a 25 percent nonpayment rate from advertisers, welcomed the space brokers, who paid up front. Brokers usually received discounts of 15 to 30 percent but sold the space to advertisers at the going rate. In 1841, Volney Palmer opened a prototype of the first ad agency in Boston; for a 25 percent commission from newspaper publishers, he sold space to advertisers.

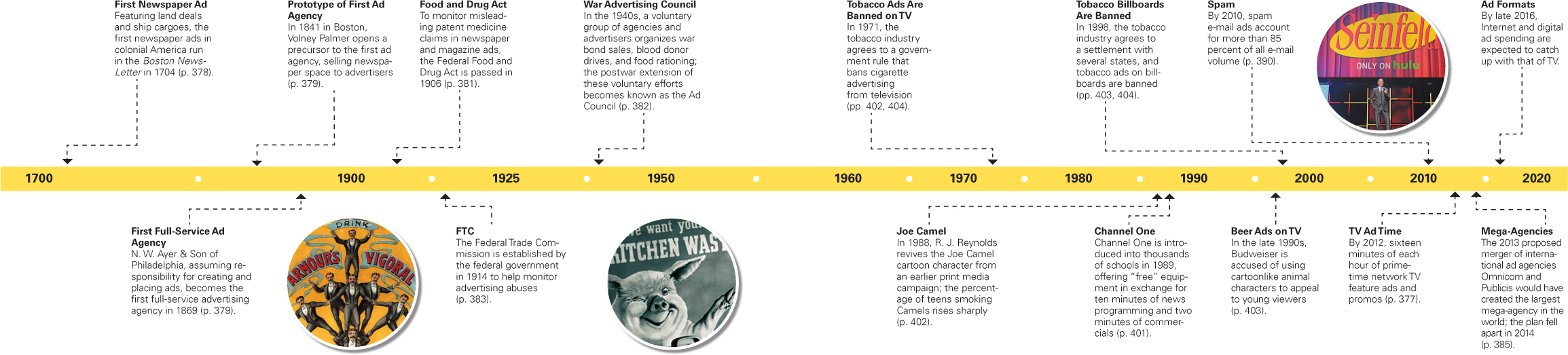

Advertising in the 1800s

The first full-

Trademarks and Packaging

During the mid-

Like many ads today, nineteenth-

One of the first brand names, Smith Brothers, has been advertising cough drops since the early 1850s. Quaker Oats, the first cereal company to register a trademark, has used the image of William Penn, the Quaker who founded Pennsylvania in 1681, to project a company image of honesty, decency, and hard work since 1877. Other early and enduring brands include Campbell Soup, which came along in 1869; Levi Strauss overalls in 1873; Ivory Soap in 1879; and Eastman Kodak film in 1888. Many of these companies packaged their products in small quantities, thereby distinguishing them from the generic products sold in large barrels and bins.

Product differentiation associated with brand-

Patent Medicines and Department Stores

PATENT MEDICINES Unregulated patent medicines, such as the one represented in this ad, created a bonanza for nineteenth-

By the end of the 1800s, patent medicines and department stores accounted for half of the revenues taken in by ad agencies. Meanwhile, one-

Many contemporary products, in fact, originated as medicines. Coca-

Along with patent medicines, department store ads were also becoming prominent in newspapers and magazines. By the early 1890s, more than 20 percent of ad space was devoted to department stores. At the time, these stores were frequently criticized for undermining small shops and businesses, where shopkeepers personally served customers. The more impersonal department stores allowed shoppers to browse and find brand-

Advertising’s Impact on Newspapers

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, “continuous-

The demand for newspaper advertising by product companies and retail stores significantly changed the ratio of copy at most newspapers. Whereas newspapers in the mid-

Promoting Social Change and Dictating Values

WAR ADVERTISING COUNCIL During World War II, the federal government engaged the advertising industry to create messages to support the U.S. war effort. Advertisers promoted the sale of war bonds; conservation of natural resources, such as tin and gasoline; and even saving kitchen waste so it could be fed to farm animals.

As U.S. advertising became more pervasive, it contributed to major social changes in the twentieth century. First, it significantly influenced the transition from a producer-

Second, advertising promoted technological advances by showing how new machines—

Appealing to Female Consumers

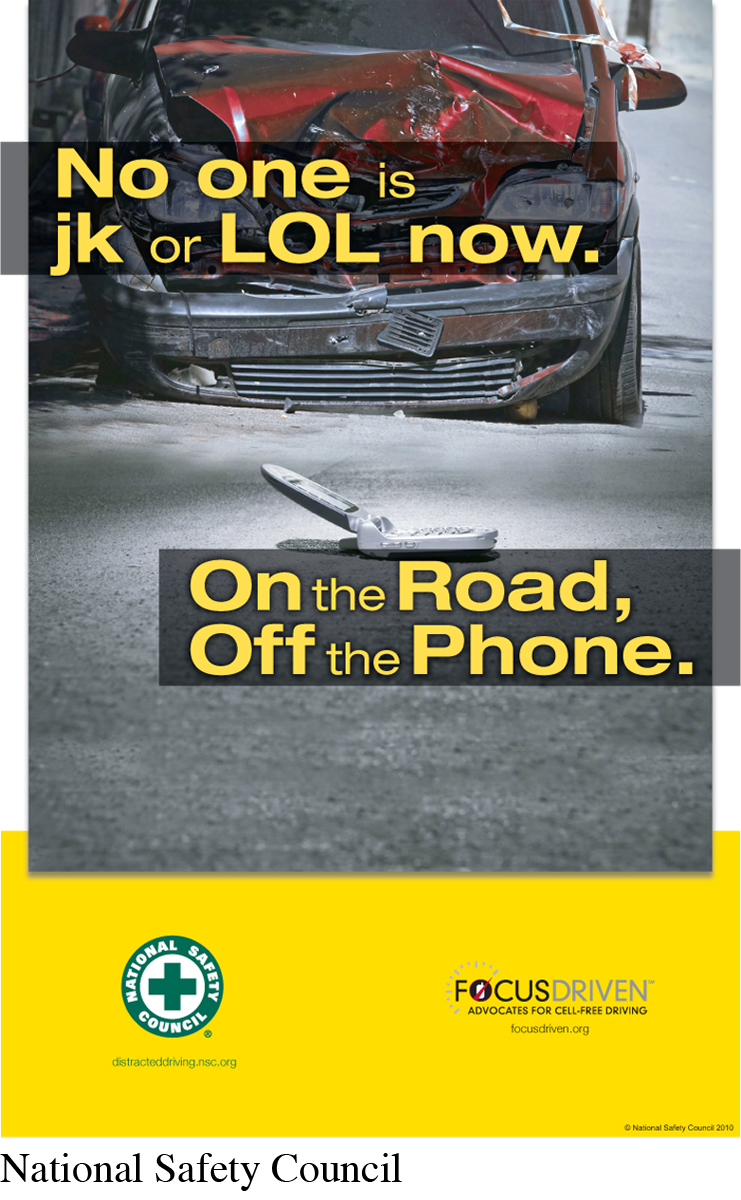

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS The Ad Council has been creating public service announcements (PSAs) since 1942. Supported by contributions from individuals, corporations, and foundations, the council’s PSAs are produced pro bono by ad agencies. This PSA is the result of the Ad Council’s long-

By the early 1900s, advertisers and ad agencies believed that women, who constituted 70 to 80 percent of newspaper and magazine readers, controlled most household purchasing decisions. (This is still a fundamental principle of advertising today.) Ironically, more than 99 percent of the copywriters and ad executives at that time were men, primarily based in Chicago and New York. They emphasized stereotyped appeals to women, believing that simple ads with emotional and even irrational content worked best. Thus, early ad copy featured personal tales of “heroic” cleaning products and household appliances. The intention was to help female consumers feel good about defeating life’s problems—

Dealing with Criticism

Although ad revenues fell during the Great Depression in the 1930s, World War II rejuvenated advertising. For the first time, the federal government bought large quantities of advertising space to promote U.S. involvement in a war. These purchases helped offset a decline in traditional advertising, as many industries had turned their attention and production facilities to the war effort.

Also during the 1940s, the industry began to actively deflect criticism that advertising created consumer needs that ordinary citizens never knew they had. Criticism of advertising grew as the industry appeared to be dictating values as well as driving the economy. To promote a more positive image, the industry developed the War Advertising Council—

The postwar extension of advertising’s voluntary efforts became known as the Ad Council. This organization has earned praise over the years for its Smokey the Bear campaign (“Only you can prevent forest fires” ); its fund-

Early Ad Regulation

The early 1900s saw the formation of several watchdog organizations. Partly to keep tabs on deceptive advertising, advocates in the business community in 1913 created the nonprofit Better Business Bureau, which now has more than one hundred branch offices in the United States. At the same time, advertisers wanted a formal service that tracked newspaper readership, guaranteed accurate audience measures, and ensured that papers would not overcharge ad agencies and their clients. As a result, publishers formed the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) in 1914 (now known as the Alliance for Audited Media).

That same year, the government created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), in part to help monitor advertising abuses. Thereafter, the industry urged self-

Finally, the advent of television dramatically altered advertising. With this new visual medium, ads increasingly intruded on daily life. Critics also discovered that some agencies used subliminal advertising. This term, coined in the 1950s, refers to hidden or disguised print and visual messages that allegedly register in the subconscious and fool people into buying products. Noted examples of subliminal ads from that time include a “Drink Coca-