The Shape of U.S. Advertising Today

Until the 1960s, the shape and pitch of most U.S. ads were determined by a slogan, the phrase that attempts to sell a product by capturing its essence in words. With slogans such as “A Diamond Is Forever” (which De Beers first used in 1948), the visual dimension of ads was merely a complement. Eventually, however, through the influence of European design, television, and (now) multimedia devices such as the iPad, images asserted themselves, and visual style became dominant in U.S. advertising and ad agencies.

The Influence of Visual Design

MAD MEN AMC’s hit series Mad Men depicts the male-

Just as a postmodern design phase developed in art and architecture during the 1960s and 1970s, a new design era began to affect advertising at the same time. Part of this visual revolution was imported from non-

By the early 1970s, agencies had developed teams of writers and artists, thus granting equal status to images and words in the creative process. By the mid-

Most recently, the Internet and multimedia devices, such as computers, mobile phones, and portable media players, have had a significant impact on visual design in advertising. As the Web became a mass medium in the 1990s, TV and print designs often mimicked the drop-

Types of Advertising Agencies

About fourteen thousand ad agencies currently operate in the United States. In general, these agencies are classified as either mega-

Mega-

Mega-

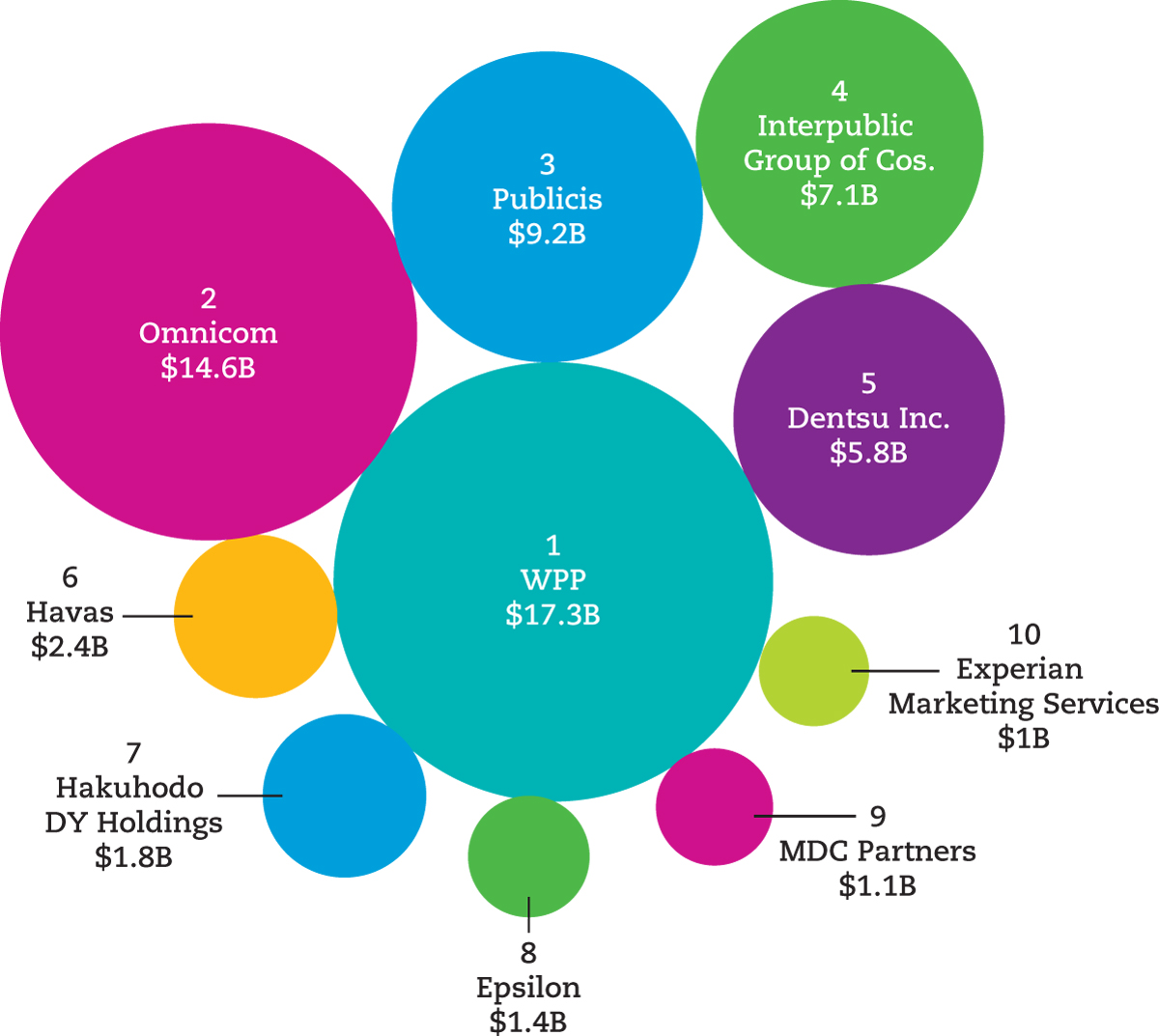

FIGURE 11.1GLOBAL REVENUE FOR THE WORLD’S LARGEST AGENCIES (IN BILLIONS OF DOLLARS)Data from: Advertising Age Marketing Fact Pack 2015, pp. 26–27.

In 2013, Omnicom and Publicis announced a merger that would have created the world’s largest mega-

The London-

This mega-

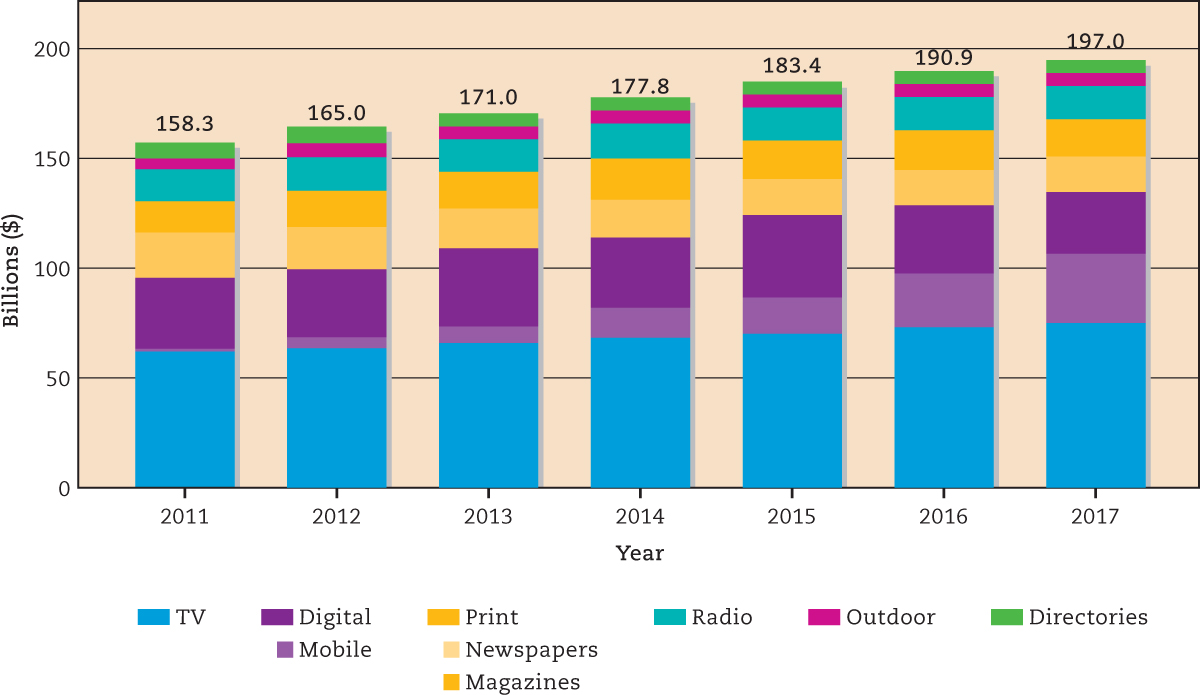

FIGURE 11.2WHERE WILL THE ADVERTISING DOLLARS GO?**Years 2015–2017 are projections.Data from: eMarketer, “US Total Media Ad Spend Inches Up, Pushed by Digital,” August 22, 2013.

Boutique Agencies

The visual revolutions in advertising during the 1960s elevated the standing of designers and graphic artists, who became closely identified with the look of particular ads. Breaking away from bigger agencies, many of these creative individuals formed small boutique agencies. Offering more personal services, the boutiques prospered, bolstered by innovative ad campaigns and increasing profits from TV accounts. By the 1980s, large agencies had bought up many of the boutiques. Nevertheless, these boutiques continue to operate as fairly autonomous subsidiaries within multinational corporate structures.

One independent boutique agency in Minneapolis, Peterson Milla Hooks (PMH), made its name with a boldly graphic national branding ad campaign for Target department stores. Target moved its business to another agency in 2011, but PMH—

The Structure of Ad Agencies

Traditional ad agencies, regardless of their size, generally divide the labor of creating and maintaining advertising campaigns among four departments: account planning, creative development, media coordination, and account management. Expenses incurred for producing the ads are part of a separate negotiation between the agency and the advertiser. As a result of this commission arrangement, it generally costs most large-

Account Planning, Market Research, and VALS

The account planner’s role is to develop an effective advertising strategy by combining the views of the client, the creative team, and consumers. Consumers’ views are the most difficult to understand, so account planners coordinate market research to assess the behaviors and attitudes of consumers toward particular products long before any ads are created. Researchers may study everything from possible names for a new product to the size of the copy for a print ad. Researchers also test new ideas and products with consumers to get feedback before developing final ad strategies. In addition, some researchers contract with outside polling firms to conduct regional and national studies of consumer preferences.

Agencies have increasingly employed scientific methods to study consumer behavior. In 1932, Young & Rubicam first used statistical techniques developed by pollster George Gallup. By the 1980s, most large agencies retained psychologists and anthropologists to advise them on human nature and buying habits. The earliest type of market research, demographics, mainly studied and documented audience members’ age, gender, occupation, ethnicity, education, and income. Today, demographic data are much more specific. They make it possible to locate consumers in particular geographic regions—

Demographic analyses provide advertisers with data on people’s behavior and social status but reveal little about feelings and attitudes. By the 1960s and 1970s, advertisers and agencies began using psychographics, a research approach that attempts to categorize consumers according to their attitudes, beliefs, interests, and motivations. Psychographic analysis often relies on focus groups, a small-

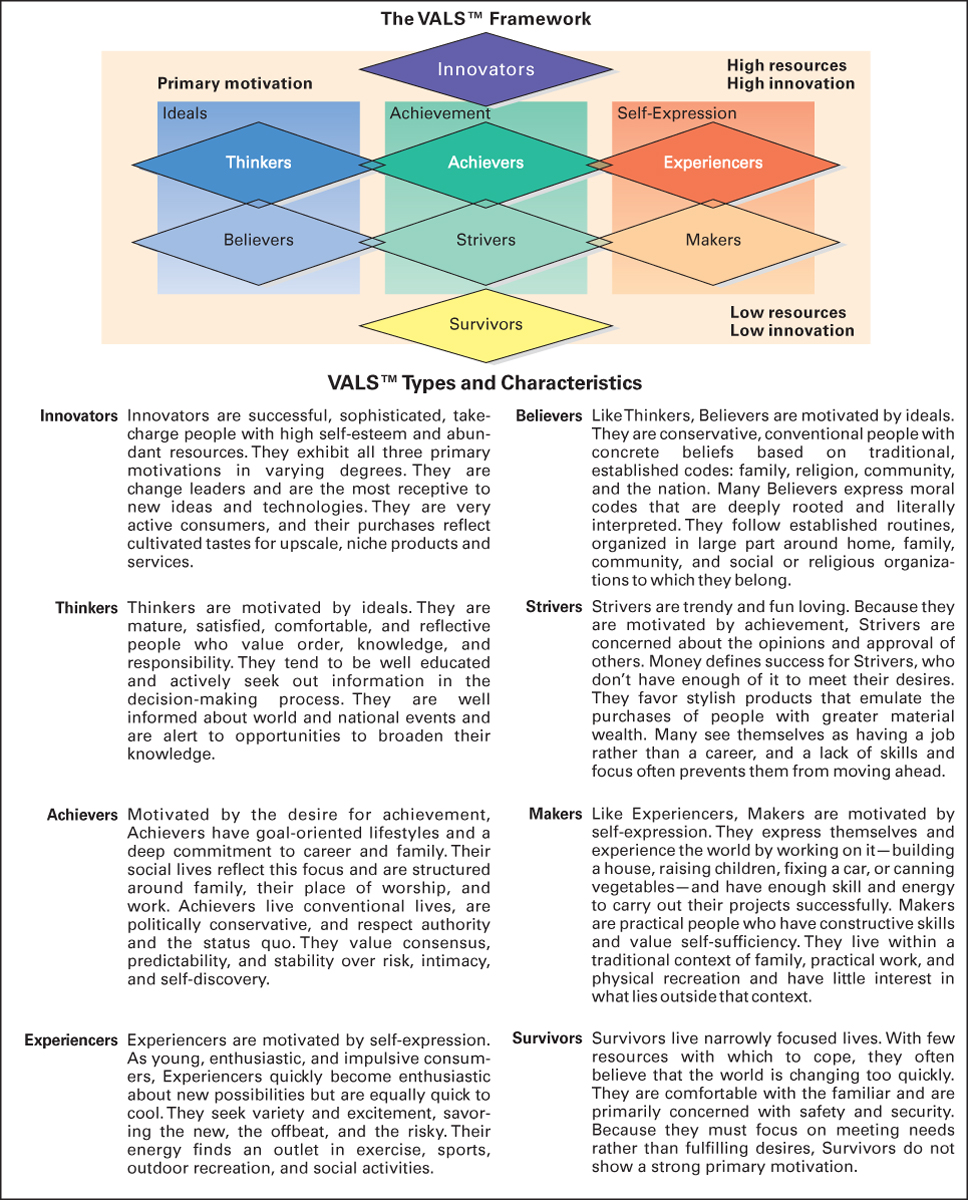

In 1978, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), now called Strategic Business Insights (SBI), instituted its Values and Lifestyles (VALS) strategy. Using questionnaires, VALS researchers measured psychological factors and divided consumers into types. VALS research assumes that not every product suits every consumer and encourages advertisers to vary their sales slants to find market niches.

Over the years, the VALS system has been updated to reflect changes in consumer orientations (see Figure 11.3). The most recent system classifies people by their primary consumer motivations: ideals, achievement, or self-

FIGURE 11.3VALS TYPES AND CHARACTERISTICSData from: Strategic Business Insights, 2010, http:/

Agencies and clients—

VALS researchers do not claim that most people fit neatly into a category. But many agencies believe that VALS research can give them an edge in markets where few differences in quality may actually exist among top-

Creative Development

Teams of writers and artists—

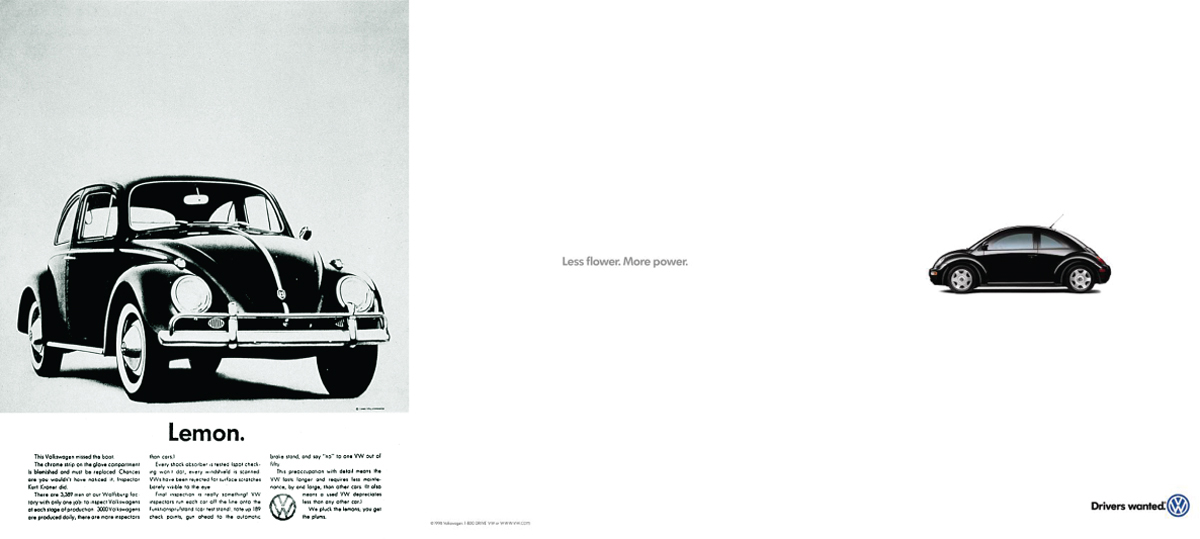

Often the creative side of the business finds itself in conflict with the research side. In the 1960s, for example, both Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) and Ogilvy & Mather downplayed research; they championed the art of persuasion and what “felt right.” Yet DDB’s simple ads for Volkswagen Beetles in the 1960s were based on weeks of intensive interviews with VW workers as well as on creative instincts. The campaign was remarkably successful in establishing the first niche for a foreign car manufacturer in the United States. Although sales of the VW Bug had been growing before the ad campaign started, the successful ads helped Volkswagen preempt the Detroit auto industry’s entry into the small-

Both the creative and the strategic sides of the business acknowledge that they cannot predict with any certainty which ads and which campaigns will succeed. Agencies say ads work best by slowly creating brand-

Media Coordination: Planning and Placing Advertising

Ad agency media departments are staffed by media planners and media buyers: people who choose and purchase the types of media that are best suited to carry a client’s ads, reach the targeted audience, and measure the effectiveness of those ad placements. For instance, a company like Procter & Gamble, currently the world’s leading advertiser, displays its more than three hundred major brands—

Along with commissions or fees, advertisers often add incentive clauses to their contracts with agencies, raising the fee if sales goals are met and lowering it if goals are missed. Incentive clauses can sometimes encourage agencies to conduct repetitive saturation advertising, in which a variety of media are inundated with ads aimed at target audiences. The initial Miller Lite beer campaign (“Tastes great, less filling”), which used humor and retired athletes to reach its male audience, became one of the most successful saturation campaigns in media history. It ran from 1973 to 1991 and included television and radio spots, magazine and newspaper ads, and billboards and point-

The cost of advertising, especially on network television, increases each year. The Super Bowl remains the most expensive program for purchasing television advertising, with thirty seconds of time costing on average $4.5 million in 2015 on Fox—

Account and Client Management

Client liaisons, or account executives, are responsible for bringing in new business and managing the accounts of established clients, including overseeing budgets and the research, creative, and media planning work done on their campaigns. This department also oversees new ad campaigns in which several agencies bid for a client’s business, coordinating the presentation of a proposed campaign and various aspects of the bidding process, such as determining what a series of ads will cost a client. Account executives function as liaisons between the advertiser and the agency’s creative team. Because most major companies maintain their own ad departments to handle everyday details, account executives also coordinate activities between their agency and a client’s in-

CREATIVE ADVERTISING The New York ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach created a famous series of print and television ads for Volkswagen beginning in 1959 (below, left) and helped usher in an era of creative advertising that combined a single-

The advertising business is volatile, and account departments are especially vulnerable to upheavals. One industry study conducted in the mid-

Trends in Online Advertising

The earliest form of Web advertising appeared in the mid-

Paid search advertising has become the dominant format of Web advertising. Even though their original mission was to provide impartial search results, search sites such as Google, Yahoo!, and Bing have quietly morphed into advertising companies, selling sponsored links associated with search terms and distributing online ads to affiliated Web pages.14

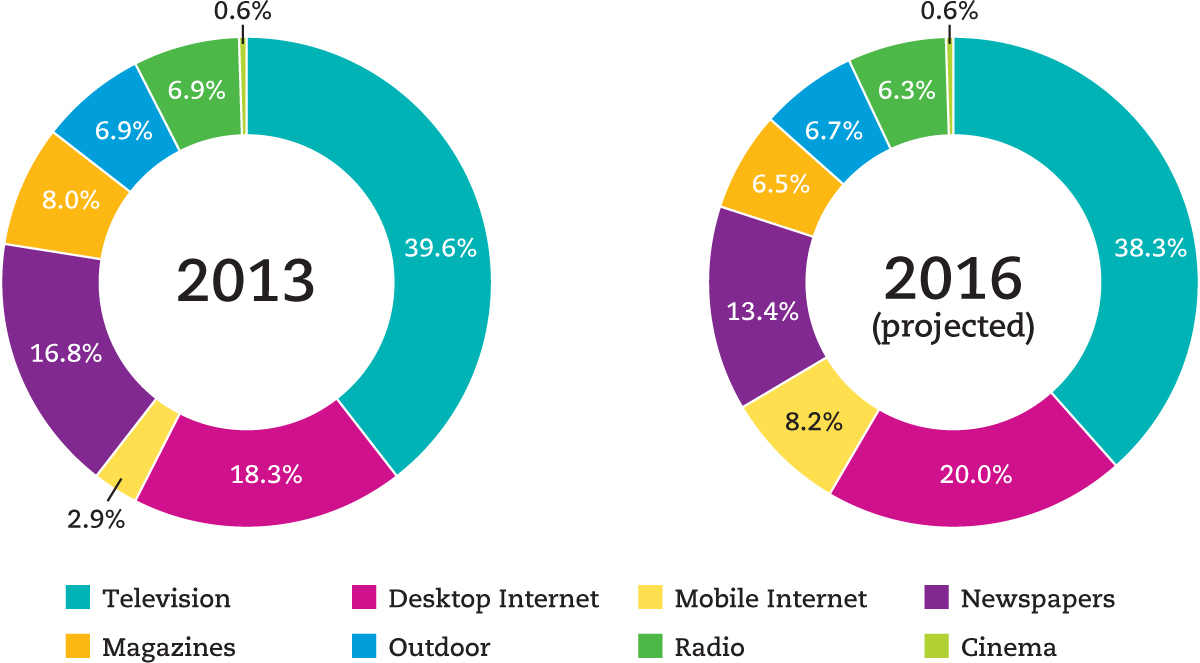

Back in 2004, digital ads accounted for just over 4 percent of global ad spending. By 2012, the Internet had gained an 18 percent share of worldwide ad spending, and in 2014, it was the second-

FIGURE 11.4SHARE OF GLOBAL AD SPENDING BY MEDIUMData from: ZenithOptimedia, in Ricardo Bilton, “The Surprising State of Digital Ad Spending in 5 Charts,” Digiday, June 17, 2014, http:/

Online Advertising Challenges Traditional Media

ONLINE ADS are mostly placed by large Internet companies like Google, Yahoo!, Microsoft, and AOL. Such services have allowed small businesses access to more customers than traditional advertising because the online ads are often cheaper to produce and are shown only to targeted users.

Because Internet advertising is the leading growth area, advertising mega-

Facebook has made its biggest strides in mobile advertising. While Google accounted for nearly 32 percent of all online global ad spending in 2013—

As the Internet draws people’s attention away from traditional mass media, leading advertisers are moving more of their ad campaigns and budget dollars to digital media. For example, the CEO of consumer product giant Unilever, a company with more than four hundred brands (including Dove, Hellmann’s, and Lipton) and a multibillion-

Online Marketers Target Individuals

Internet ads offer many advantages to advertisers, compared to ads in traditional media outlets like newspapers, magazines, radio, or television. Perhaps the biggest advantage—

Internet advertising agencies can also track ad impressions (how often ads are seen) and click-

Beyond computers, smartphones—

Advertising Invades Social Media

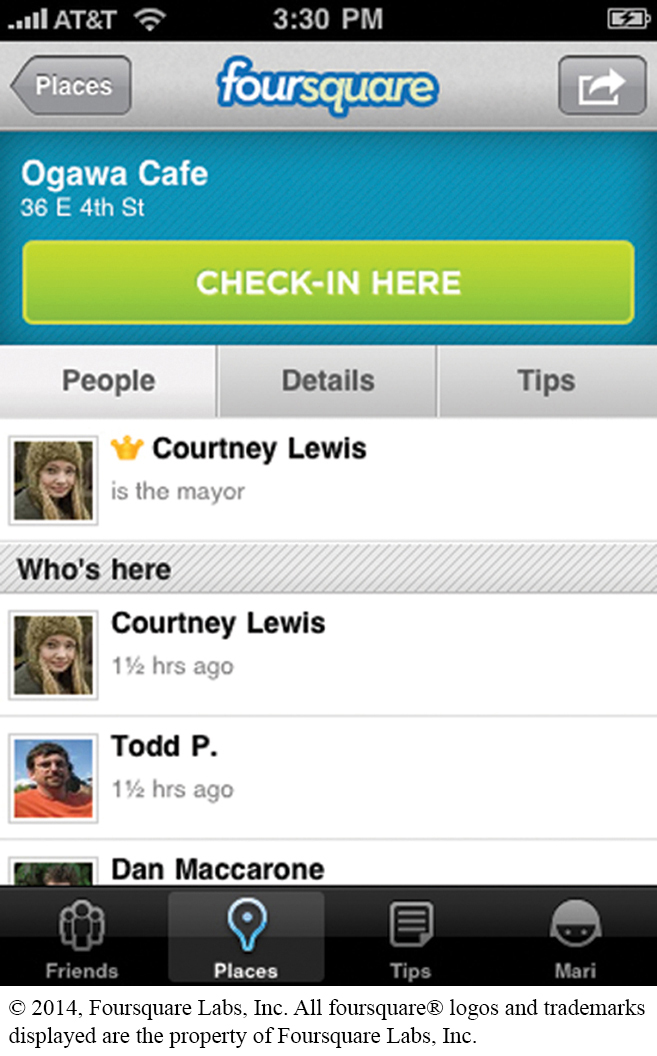

Social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Foursquare, provide a wealth of data for advertisers to mine. These sites and apps create an unprecedented public display of likes, dislikes, locations, and other personal information. And advertisers are using such information to further refine their ability to send targeted ads that might interest users. Facebook and other sites (like Hulu) go even further by asking users if they liked the ad or not. For example, clicking off a display ad in Facebook results in the question “Why didn’t you like it?” followed by the choices “uninteresting,” “misleading,” “offensive,” “repetitive,” and “other.” All that information goes straight back to advertisers so they can revise their advertising and try to engage you the next time. Beyond allowing advertisers to target and monitor their ad campaigns, most social media encourage advertisers to create their own online identity. For example, Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream’s Facebook page has more than seven million “friends.” Despite appearances, such profiles and identities still constitute a form of advertising and serve to promote products to a growing online audience for virtually no cost.

FOURSQUARE is using its recent popularity to increase revenues by partnering with businesses to provide “specials” to Foursquare users and “mayors.” While it may seem like a great deal to offer free snacks or drinks to users, what Foursquare is really offering to businesses (“venues”) is the chance to mine data and “be able to track how your venue is performing over time thanks to [Foursquare’s] robust set of venue analytics.”

Companies and organizations also buy traditional paid advertisements on social media sites. A major objective of their paid media is to get earned media, or to convince online consumers to promote products on their own. Imagine that the environmental group the National Resources Defense Council buys an ad on Facebook that attracts your interest. That’s a successful paid media ad for the council, but it’s even more effective if it becomes earned media—

A recent controversy in online advertising is whether people have to disclose if they are being paid to promote a product. For example, bloggers often review products or restaurants as part of their content. Some bloggers with large followings have been paid (either directly or by “gifts” of free products or trips) to give positive reviews or promote products on their site. When such instances, dubbed “blog-