Analyzing the Media Economy

Given the sprawling scope of the mass media, the study of their economic conditions poses a number of complicated questions:

What role does the government need to play in determining who owns the mass media and what kinds of media products are manufactured? Should it be a strong role, or should the government step back and let competition and market forces dictate what happens to mass media industries?

Should citizen groups play a larger part in demanding that media organizations help maintain the quality of social and cultural life?

Does the influence of American popular culture worldwide smother or encourage the growth of democracy and local cultures?

Does the increasing concentration of economic power in the hands of several international corporations too severely restrict the number of players and voices in the media?

Answers to such questions span the economic and social spectrums. On the one hand, critics express concerns about the increasing power and reach of large media conglomerates. On the other hand, many free-

In order to probe these issues fully, we need to understand key economic concepts across two broad areas: media structure and media performance.3

The Structure of the Media Industry

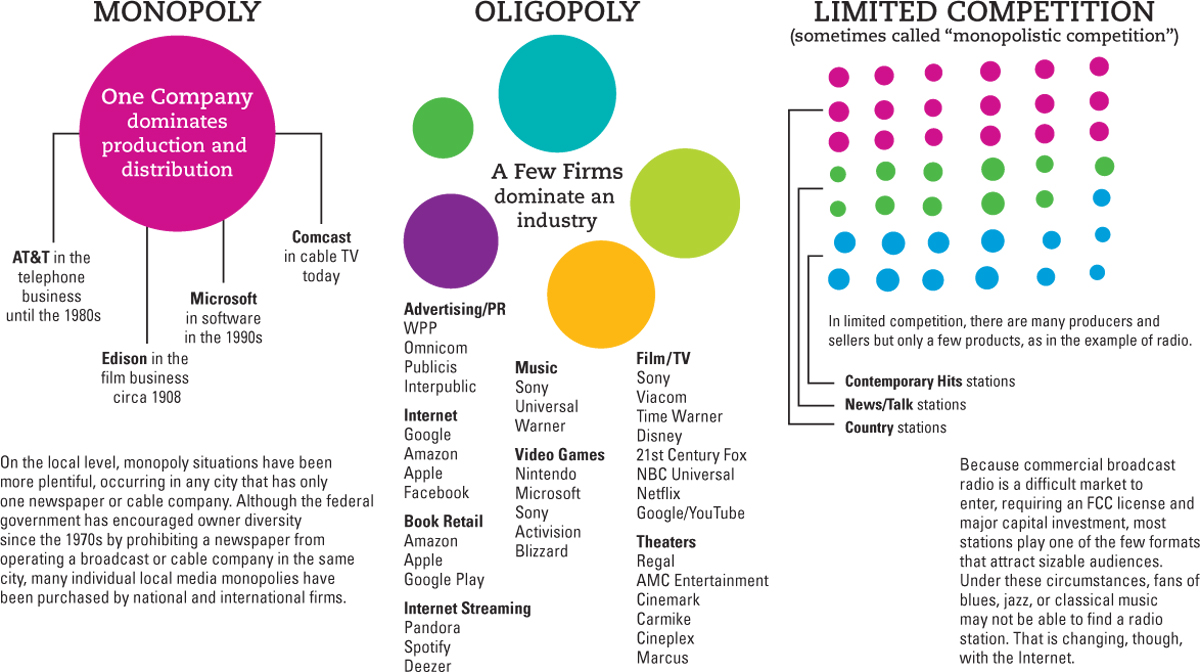

Media industries are typically structured in one of three ways: as a monopoly, an oligopoly (the most common structure), or a limited competition (typical of the radio and newspaper industries).4 For a detailed explanation of these structures, refer to Figure 13.1.

FIGURE 13.1MEDIA INDUSTRY STRUCTURES

The Performance of Media Organizations

In analyzing the performance of media organizations, economists pay attention to a number of elements—

Collecting Revenue

The media collect revenues in two ways: through direct and indirect payments. Direct payment involves media products supported primarily by consumers, who pay directly for a book, a movie, a music download, or an Internet or cable TV service. Indirect payment involves media products supported primarily by advertisers, who pay for the quantity or quality of audience members that a particular medium delivers. Over-

Through direct payments, consumers communicate their preferences immediately. Through the indirect payments of advertising, “the client is the advertiser, not the viewer or listener or reader,” according to media economist Douglas Gomery.5 Advertisers, in turn, seek media channels that persuade customers to acquire new products or switch brand loyalties.

Many forms of mass media, of course, generate revenue both directly and indirectly, including newspapers, magazines, some video games, online services, and cable systems.

Media Economics and the Global Marketplace

Commercial Strategies

OPRAH WINFREY has built a remarkable media empire over the course of her long career. From book publishing to filmmaking and television, where she got her start, Oprah has established an expansive sphere of influence. After ending her talk show, she launched the cable TV network OWN in 2011, which after a slow start moved toward stability on the strength of scripted television programs.

When selling media content (and selling their audience to their advertising clients), media industry executives look to the most advantageous balance in the commercial process, including program or product costs, price setting, marketing strategies, and regulatory practices. Following are some common questions for every media industry.

Price. How high can the price be raised of a book, movie, video game, music download, or Internet service before people won’t buy it? How much can Netflix charge per month before its subscribers begin to switch to competing services?

Length, Frequency, and Tolerance. How long will people tolerate a commercial break before they switch the channel or click on something else? For example, how many seconds should Google allow a commercial to run prior to a desired YouTube video before a user can “skip the ad”?

Data Mining and Privacy. How much data can media companies such as Google or Facebook collect on customers before they find it an invasion of privacy?

Regulation. For example, how much advertising of alcohol to underage audiences can a media company get away with before drawing the attention of media critics, consumer organizations, and regulatory boards?

Economists, media critics, and consumer organizations have also asked the mass media to meet certain performance criteria. Some key expectations of media organizations include:

Introducing new technologies to the marketplace (e.g., improving the speed of broadband connections)

Making media products and services available to people of all economic classes

Facilitating free expression and robust political discussion

Monitoring society in times of crisis

Playing a positive role in education

Maintaining the quality of culture6

Although media industries live up to some of these expectations better than others, economic analyses permit consumers and citizens to examine the instances when the mass media fall short. For example, when corporate executives trim news budgets or fire news personnel, or use one reporter to do multiple versions of a story for TV, radio, newspaper, and the Internet, such decisions ultimately reduce the total number of distinct news stories that cover a crucial topic and jeopardize the role of journalists as watchdogs of society. Media economic decisions thus affect the society in which we live.