The Transition to an Information Economy

The twentieth century can be divided in two. The first half of the century emphasized mass production, assembly lines, the rise of manufacturing plants, and the intense rivalry between U.S.-based businesses and businesses from other nations that produced competing products. By the 1950s, however, the U.S. economy was beginning a transition to a new cooperative global economy as the machines that drove the Industrial Age changed gears for the new Information Age. Offices slowly displaced factories as major work sites; centralized mass production declined and often gave way to internationalized, decentralized, and lower-

As part of the shift to an information-

Deregulation Trumps Regulation

ANTITRUST REGULATION During the late nineteenth century, John D. Rockefeller Sr., considered the richest businessman in the world, controlled more than 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining business. But antitrust regulations were used in 1911 to bust up Rockefeller’s powerful Standard Oil into more than thirty separate companies. He later hired PR guru Ivy Lee to refashion his negative image as a greedy corporate mogul.

During the rise of industry in the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs such as John D. Rockefeller in oil, Cornelius Vanderbilt in shipping and railroads, and Andrew Carnegie in steel created monopolies in their respective industries. There was so little regulation of these newly powerful industries that the companies became notorious for their exploitative labor practices (including child labor), corrupt corporate conduct, and manipulation of the competitive landscape. Corporations and their business partners were often organized as “trusts,” but soon the word trust became equated with any large corporation—

In 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, prohibiting manufacturers from selling only to dealers and contractors who agree to reject the products of business rivals. The Celler-

Deregulation Spurs Formation of Media Conglomerates

The corporate regulations introduced between 1890 and 1950 were meant to increase competition between companies and prevent any one company from having too much control over the market. However, corporations chafed under these economic rules, and with the rise of public relations tactics and aggressive lobbying campaigns from the 1920s onward, they worked to turn the anticorporate rhetoric so prominent throughout the first half of the twentieth century (particularly in light of the Great Depression) into a commonsense narrative that government regulation was bad for business and bad for America.7 Although the administration of President Jimmy Carter (1977–1981) actually initiated deregulation, most controls on business were drastically weakened under President Ronald Reagan (1981–1989). Deregulation led to easier mergers, corporate diversifications, and increased tendencies in some sectors toward oligopolies (especially in air travel, energy, finance, and communications).8

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 (signed by President Bill Clinton) brought unprecedented deregulation to a broadcast industry that had been closely regulated for more than sixty years. The act transformed the industry:

A single company could now own an almost unlimited number of radio and TV stations.

Telephone companies could now own TV and radio stations.

Cable companies could now compete in the local telephone business.

Cable companies could freely raise rates.

Prior to this, a company could own no more than twenty AM, twenty FM, and twelve TV stations. After the act, several corporations quickly grew to owning hundreds of stations. As a result, radio and television ownership became increasingly consolidated. At the time, some economists thought the new competition would lower consumer prices. Others predicted more mergers and an oligopoly in which a few megacorporations would control most of the wires entering a home and thus dictate pricing.

As it turned out, the latter group was right. Ever-

Media Powerhouses: Consolidation, Partnerships, and Mergers

MEDIA ACQUISITIONS like Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal enable a distribution company (Comcast) to also control the production (by NBC Universal) of much of its content. Comcast, the largest cable and broadband provider in the United States, now owns many of the channels that appear on its cable systems. Yet this does not guarantee NBC Universal production a spot on one of those channels. The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, originally intended for NBC, was sold instead to Netflix, where it became a success for the streaming company. NBC Universal can make money even when it doesn’t air its own shows.

Despite their strength, the antitrust laws of the twentieth century have been unevenly applied, especially in terms of the media. When International Telephone & Telegraph (ITT) tried to acquire ABC in the 1960s, loud protests and government investigations sank the deal. But in the mid-

In 1995, Disney acquired ABC for $19 billion. To ensure its rank as the world’s largest media conglomerate, Time Warner countered and bought Turner Broadcasting in 1995 for $7.5 billion. In 2001, AOL acquired Time Warner for $164 billion—

Also in 2001, the federal government approved a $72 billion deal uniting AT&T’s cable division with Comcast, creating a cable company twice the size of its nearest competitor. (AT&T quickly left the merger, selling its cable holdings to Comcast for $47 billion in late 2001.) In 2009, Comcast struck a deal with GE to purchase a majority stake in NBC Universal, stirring up antitrust complaints from some consumer groups. In 2010, Congress began hearings on whether uniting a major cable company and a major broadcasting network under a single owner would decrease healthy competition between cable and broadcast TV and thus hurt consumers. In 2011, the FCC approved the deal.

Until the 1980s, antitrust rules attempted to ensure diversity of ownership among competing businesses. Sometimes this happened, as in the breakup of AT&T, and sometimes it did not, as in the cases of cable monopolies and the mergers just discussed. What has occurred consistently, however, is media competition being usurped by media consolidation. Today, the same anticompetitive mind-

Most media companies have skirted monopoly charges by purchasing diverse types of mass media rather than trying to control just one medium. For example, Disney, rather than trying to dominate one area, provides programming to TV, cable, and movie theaters. In 1995, then CEO Michael Eisner defended the company’s practices, arguing that as long as large companies remain dedicated to quality—

But Eisner’s position raises questions: How is the quality of cultural products determined? If companies cannot make money on quality products, what happens? If ABC News cannot make a substantial profit, should Disney’s managers cut back its national or international news staff? What are the potential effects of such layoffs on the public mission of news media and consequently on our political system? How should the government and citizens respond?

Business Tendencies in Media Industries

In addition to the consolidation trend, a number of other factors characterize the economics of mass media businesses. These are general trends or tendencies that cut across most business sectors and demonstrate how contemporary global economies operate.

Flexible Markets and the Decline of Labor Unions

Geographer David Harvey has observed that today’s information culture is characterized by what business executives call flexibility—

Given that 80 to 90 percent of new consumer and media products typically fail, a flexible economy has demanded rapid product development and efficient market research. Companies need to score a few hits to offset investments in failed products. For instance, during the peak summer movie season, studios premiere dozens of new feature films, such as Jurassic World, San Andreas, and Trainwreck in 2015. A few are big hits but many more miss, and studios hope to recoup their losses via merchandising tie-

The era of flexible markets also coincided with the decline in the number of workers who belong to labor unions. Having made strong gains on behalf of workers after World War II, labor unions, at their peak in 1954, represented 34.8 percent of U.S. workers. Then manufacturers and other large industries began to look for ways to cut labor costs, which had increased as then-

Downsizing and the Wage Gap

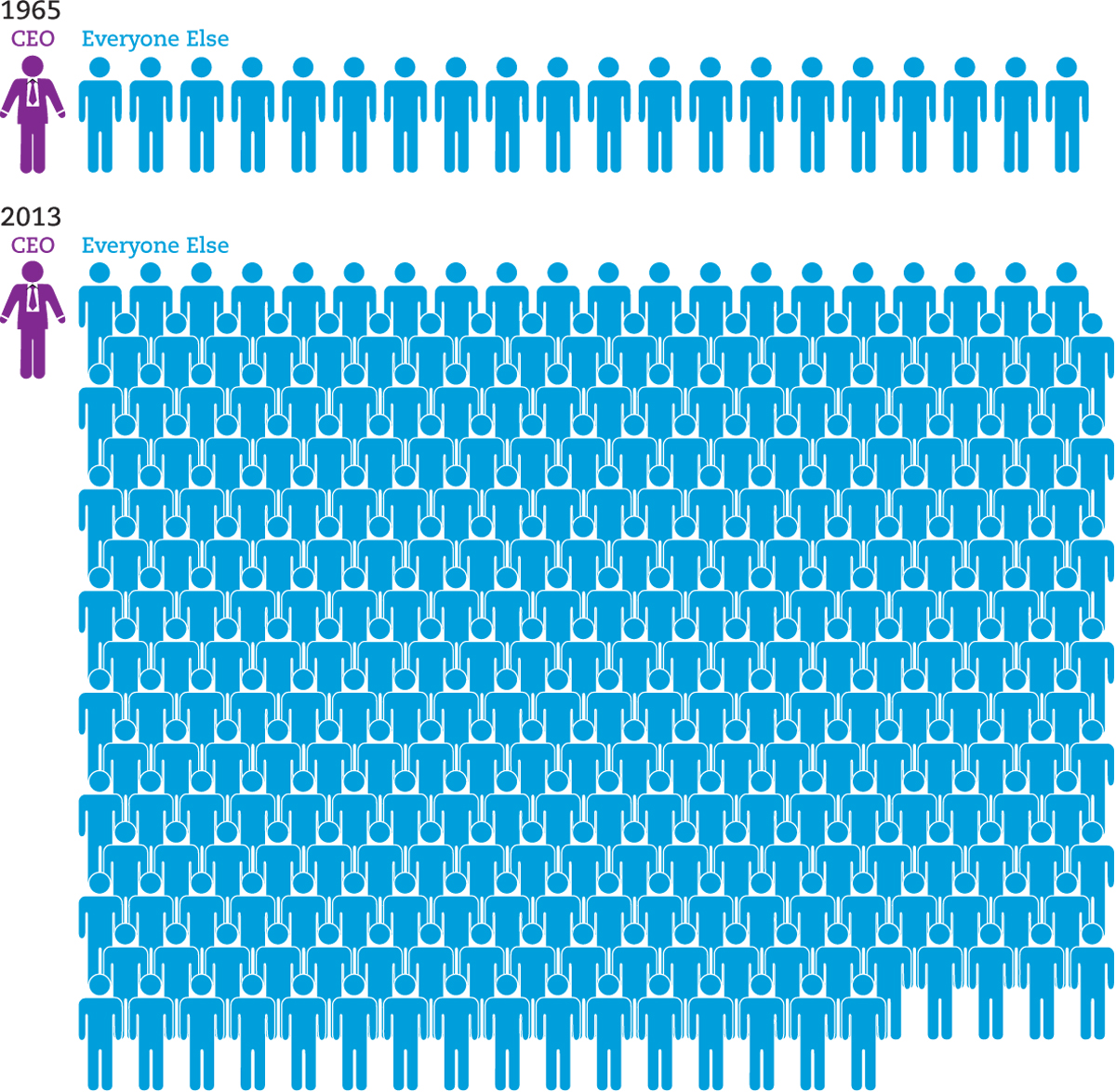

FIGURE 13.2CEO-

With the apparent advantage to large companies in this flexible age, who is disadvantaged? From the beginning of the recession in December 2007 through 2009, the United States lost more than 8.4 million jobs (affecting 6.1 percent of all employers), creating the highest unemployment contraction since the Great Depression.14 The unemployment rate started to recede in 2009, but from 2009 to 2012, as the economy slowly recovered, 95 percent of postrecession income growth was captured by the top 1 percent—

Inequality in the United States between the richest and everyone else has been growing since the 1970s. This is apparent in the skyrocketing rate of executive compensation and the growing ratio between executive pay and the typical pay of workers in corresponding industries. In 1965, the CEO-

Corporate downsizing, which is supposed to make companies more flexible and more profitable, has served CEOs well but has not served workers well. This trend, spurred by government deregulation and a decline in worker protections, means that many employees today scramble for jobs, often working two or three part-

Economics, Hegemony, and Storytelling

To understand why our society hasn’t (until recently) participated in much public discussion about wealth disparity and salary gaps, it is helpful to understand the concept of hegemony. The word hegemony has roots in ancient Greek, but in the 1920s and 1930s, Italian philosopher and activist Antonio Gramsci worked out a modern understanding of hegemony: how a ruling class in a society maintains its power—

How, then, does this process actually work in our society? How do lobbyists, the rich, and our powerful two-

So if companies or politicians convinced consumers and voters that the interests of the powerful were common sense and therefore normal or natural, they also created an atmosphere and context in which there was less chance for challenge and criticism. Common sense, after all, repels self-

To argue that a particular view or value is common sense is often an effective strategy for stopping conversation and debate. Yet common sense is socially and symbolically constructed and shifts over time. For example, it was once common sense that the world was flat and that people who were not property-

To buy uncritically into concepts presented as common sense inadvertently serves to maintain such concepts as natural, shutting down discussions about the ways in which economic divisions or political hierarchies are not natural and given. So when Democratic and Republican candidates run for office, the stories they tell about themselves espouse their connection to Middle American common sense and down-

To understand how hegemony works as a process, let’s examine how common sense is practically and symbolically transmitted. Here it is crucial to understand the central importance of storytelling to culture. The narrative—

AMERICAN DREAM STORIES are distributed through our media. This is especially true of television shows in the 1950s and 1960s like The Donna Reed Show, which idealized the American nuclear family as central to the American Dream.

The reason that common narratives work is that they identify with a culture’s dominant values; Middle American virtues include allegiances to family, honesty, hard work, religion, capitalism, health, democracy, moderation, loyalty, fairness, authenticity, modesty, and so forth. These kinds of Middle American virtues are the ones that our politicians most frequently align themselves with in the political ads that tell their stories. These virtues lie at the heart of powerful American Dream stories that for centuries have told us that if we work hard and practice such values, we will triumph and be successful. Hollywood, too, distributes these shared narratives, celebrating characters and heroes who are loyal, honest, and hardworking. Through this process, the media (and the powerful companies that control them) provide the commonsense narratives that keep the economic status quo relatively unchallenged and leave little room for alternatives.

In the end, hegemony helps explain why we occasionally support economic plans and structures that may not be in our best interest. We may do this out of altruism, as when wealthy people or companies favor higher taxes because of a sense of obligation to support those who are less fortunate. But more often, the American Dream story is so powerful in our media and popular culture that many of us believe that we have an equal chance of becoming rich and therefore successful and happy. So why would we do anything to disturb the economic structures that the dream is built on? In fact, in many versions of our American Dream story—