Journalism in the Age of TV and the Internet

The rules and rituals governing American journalism began shifting in the 1950s. At the time, former radio reporter John Daly hosted the CBS network game show What’s My Line? When he began moonlighting as the evening TV news anchor on ABC, the network blurred the entertainment and information border, foreshadowing what was to come.

In the early days, the most influential and respected television news program was CBS’s See It Now. Coproduced by Fred Friendly and Edward R. Murrow, See It Now practiced a kind of TV journalism lodged somewhere between the neutral and narrative traditions. Generally regarded as “the first and definitive” news documentary on American television, See It Now sought “to report in depth—

Differences between Print, TV, and Internet News

Although TV news reporters share many values, beliefs, and conventions with their print counterparts, television transformed journalism in a number of ways. First, broadcast news is driven by its technology. If a camera crew and news van are dispatched to a remote location for a live broadcast, reporters are expected to justify the expense by developing a story, even if nothing significant is occurring. For instance, when a national political candidate does not arrive at the local airport in time for an interview on the evening news, the reporter may cover a flight delay instead. Print reporters, in contrast, slide their notebooks or laptops back into their bags and report on a story when it occurs. However, with print reporters now posting regular online updates to their stories, they offer the same immediacy that live television news reporting does. In fact, in most newsrooms today, the online version of a story is often posted before the newspaper or TV version appears.

Second, while print editors cut stories to fit the physical space around ads, TV news directors have to time stories to fit between commercials. Despite the fact that a much higher percentage of space is devoted to print ads (about 60 percent at most dailies), TV ads (which take up less than 25 percent of a typical thirty-

Third, while modern print journalists are expected to be detached, TV news derives its credibility from live, on-

By the mid-

Few stations around the country have responded to viewers and critics who complain about the overemphasis on crime. (In reality, FBI statistics reveal that crime and murder rates have fallen or leveled off in most major urban areas since the 1990s.) In 1996, the news director at KVUE-

Pretty-

MORNING NEWS SHOWS are closely tended patches of the network news landscape. Competition between shows like Today and Good Morning America remains intense, and network executives sometimes intervene to make “fixes,” like the controversial 2012 reassignment of former Today anchor Ann Curry. Good Morning America has received a lot of press for its recent victories over its longtime rival Today.

In the early 1970s at a Milwaukee TV station, consultants advised the station’s news director that the evening anchor looked too old. The anchor, who showed a bit of gray, was replaced and went on to serve as the station’s editorial director. He was thirty-

Such stories are rampant in the annals of TV news. They have helped create a stereotype of the half-

Another strategy favored by news consultants is happy talk: the ad-

Sound Bitten

Beginning in the 1980s, the term sound bite became part of the public lexicon. The TV equivalent of a quote in print news, a sound bite is the part of a broadcast news report in which an expert, a celebrity, a victim, or a person-

Pundits, “Talking Heads,” and Politics

ANDERSON COOPER has been the primary anchor of Anderson Cooper 360° since 2003. Although the program is mainly taped and broadcast from his New York City studio, and typically features reports of the day’s main news stories with added analyses from experts, Cooper is one of the few “talking heads” who still reports live fairly often from the field for major news stories. Notably, he has done extensive coverage of the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico (below), the February 2011 uprisings in Egypt, and the devastating earthquake in Japan in 2011.

The transformation of TV news by cable—

Today’s main cable channels have built their evening programs along partisan lines and follow the model of journalism as opinion and assertion: Fox News goes right with pundit stars like Bill O’Reilly (the ratings king of cable news) and Sean Hannity; MSNBC leans left with Rachel Maddow and Lawrence O’Donnell; and CNN stakes out the middle with hosts who try to strike a more neutral pose, like Anderson Cooper. CNN, the originator of cable news, does much more original reporting than Fox News and MSNBC and does better in nonpresidential election years, as well as during natural disasters and crime tragedies. After some up and down years, CNN dropped to a twenty-

Today’s cable and Internet audiences seem to prefer partisan talking heads over traditional reporting. This suggests that in today’s fragmented media marketplace, going after niche audiences along political lines is smart business—

Convergence Enhances and Changes Journalism

For mainstream print and TV reporters and editors, online news has added new dimensions to journalism. Both print and TV news can continually update breaking stories online, and many reporters now post their online stories first and then work on traditional versions. This means that readers and viewers no longer have to wait until the next day for the morning paper or for the local evening newscast for important stories. To enhance the online reports, which do not have the time or space constraints of television or print, newspaper reporters are increasingly required to provide video or audio for their stories. This might allow readers and viewers to see full interviews rather than just selected print quotes in the paper or short sound bites on the TV report.

However, online news comes with a special set of problems. Print reporters, for example, can conduct e-

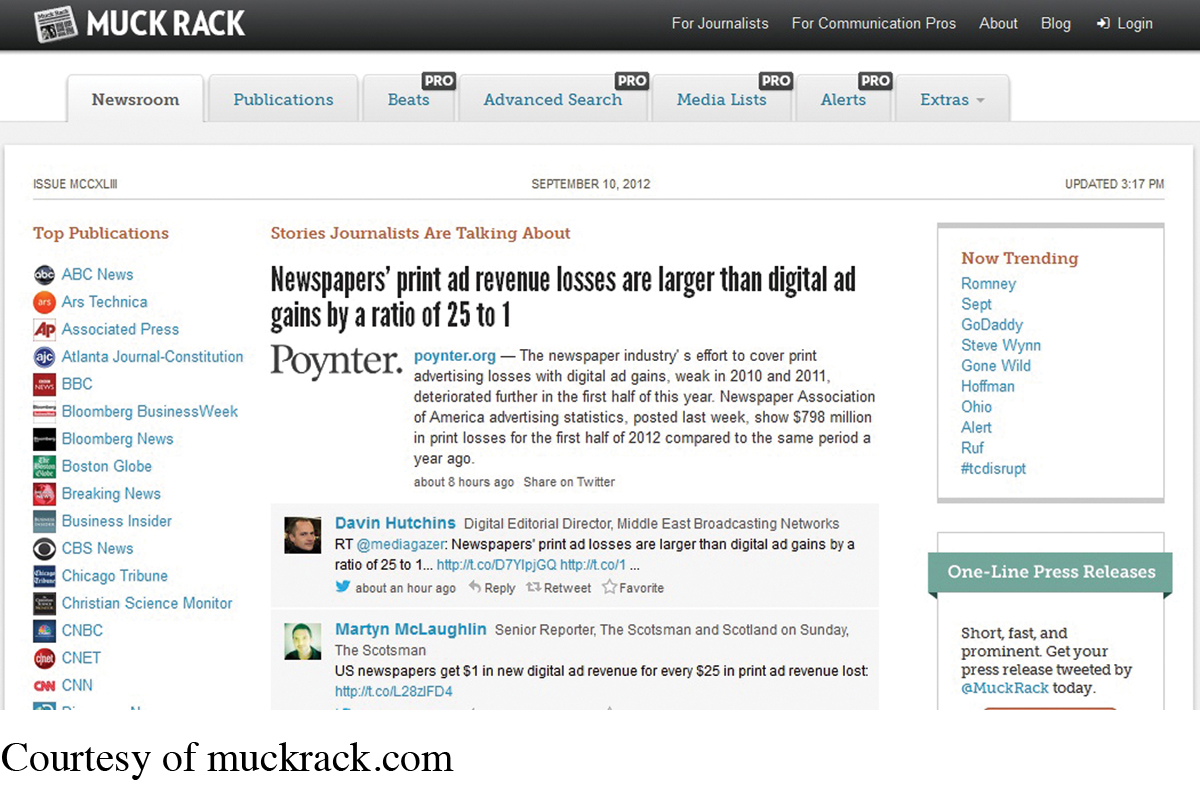

NEWS IN THE DIGITAL AGE Today, more and more journalists use Twitter in addition to performing their regular reporting duties. Muck Rack collects journalists’ tweets in one place, making it easier than ever to access breaking news and real-

Another problem for journalists, ironically, is the wide-

Most notable, however, for journalists in the digital age are the demands that convergence has made on their reporting and writing. Print journalists at newspapers (and magazines) are expected to carry digital cameras so they can post video along with the print versions of their stories. TV reporters are expected to write print-

The Power of Visual Language

The shift from a print-

Other enduring TV images are also embedded in the collective memory of many Americans: the Kennedy and King assassinations in the 1960s; the turmoil of Watergate in the 1970s; the first space shuttle disaster and the Chinese student uprisings in the 1980s; the Oklahoma City federal building bombing in the 1990s; the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center in 2001; Hurricane Katrina in 2005; the historic election of President Obama in 2008; the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011; and the brutal murders of twenty schoolchildren and six adults in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012. During these critical events, TV news has been a cultural reference point, marking the strengths and weaknesses of our world.

Today, the Internet, for good or bad, functions as a repository for news images and video, alerting us to stories that the mainstream media missed or to videos captured by amateurs. Everyone remembers the video leaked to Mother Jones magazine in which candidate Mitt Romney proclaimed at a 2012 campaign fund-