Film and the First Amendment

When the First Amendment was ratified in 1791, even the most enlightened leaders of our nation could not have predicted the coming of visual media such as film and television. Consequently, new communication technologies have not always received the same kinds of protection under the First Amendment as those granted to speech or print media, including newspapers, magazines, and books. Movies, in existence since the late 1890s, only earned legal speech protection after a 1952 Supreme Court decision. Prior to that, social and political pressures led to both censorship and self-

Social and Political Pressures on the Movies

During the early part of the twentieth century, movies rose in popularity among European immigrants and others from modest socioeconomic groups. This, in turn, spurred the formation of censorship groups, which believed that the movies would undermine morality. During this time, according to media historian Douglas Gomery, criticism of movies converged on four areas: “the effects on children, the potential health problems, the negative influences on morals and manners, and the lack of a proper role for educational and religious institutions in the development of movies.”18

Public pressure on movies came both from conservatives, who saw them as a potential threat to the authority of traditional institutions, and from progressives, who worried that children and adults were more attracted to movie houses than to social organizations and urban education centers. As a result, civic leaders publicly escalated their pressure, organizing local review boards that screened movies for their communities. In 1907, the Chicago City Council created an ordinance that gave the police authority to issue permits for the exhibition of movies. By 1920, more than ninety cities in the United States had some type of movie censorship board made up of vice squad officers, politicians, and citizens. By 1923, twenty-

Meanwhile, social pressure began to translate into law as politicians, wanting to please their constituencies, began to legislate against films. Support mounted for a federal censorship bill. When Jack Johnson won the heavyweight championship in 1908, boxing films became the target of the first federal censorship law aimed at the motion-

The first Supreme Court decision regarding film’s protection under the First Amendment was handed down in 1915 and went against the movie industry. In Mutual v. Ohio, the Mutual Film Company of Detroit sued the state of Ohio, whose review board had censored a number of the distributor’s films. On appeal, the case arrived at the Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled that motion pictures were not a form of speech but “a business pure and simple” and, like a circus, merely a “spectacle” for entertainment with “a special capacity for evil.” This ruling would stand as a precedent for thirty-

Self-

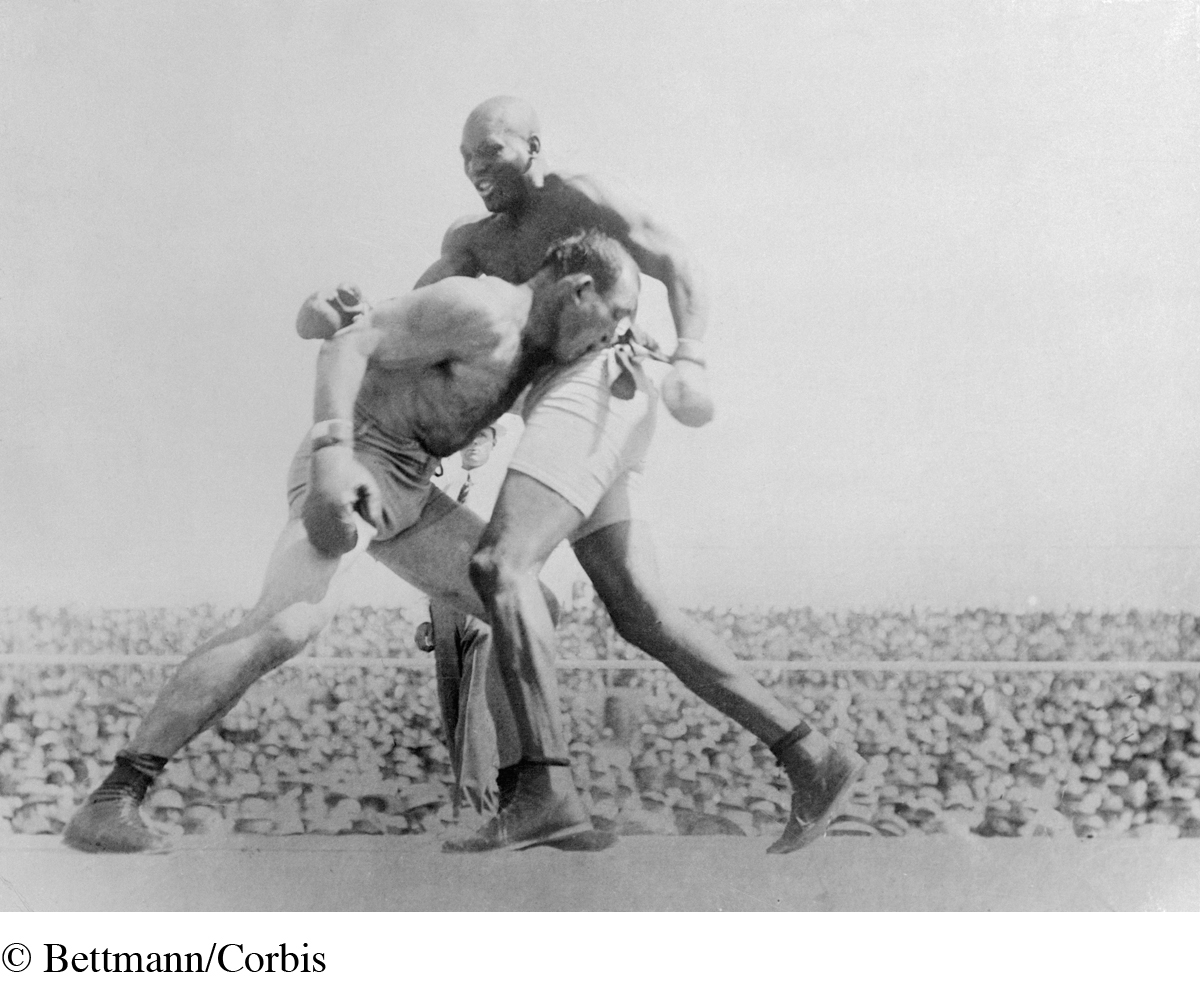

CENSORSHIP A native of Galveston, Texas, Jack Johnson (1878–1946) was the first black heavyweight boxing champion, from 1908 to 1914. His stunning victory over white champion Jim Jeffries (who had earlier refused to fight black boxers) in 1910 resulted in race riots across the country and led to a ban on the interstate transportation of boxing films. A 2005 Ken Burns documentary, Unforgivable Blackness, chronicles Johnson’s life.

As the film industry expanded after World War I, the impact of public pressure and review boards began to affect movie studios and executives who wanted to ensure control over their economic well-

In response to the scandals, particularly the first Arbuckle trial, the movie industry formed the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) and hired as its president Will Hays, a former Republican National Committee chair. Also known as the Hays Office, the MPPDA attempted to smooth out problems between the public and the industry. Hays blacklisted promising actors or movie extras with even minor police records. He also developed an MPPDA public relations division, which stopped a national movement for a federal law censoring movies.

The Motion Picture Production Code

During the 1930s, the movie business faced a new round of challenges. First, various conservative and religious groups—

The Code laid out its mission in its first general principle: “No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrong-

Adopted by 95 percent of the industry, the Code influenced nearly every commercial movie made between the mid-

The Miracle Case

In 1952, the Supreme Court heard the Miracle case—

The MPAA Ratings System

The current voluntary movie rating system—

| Rating | Description |

| G | General Audiences: Nothing that would offend parents for viewing by their children. |

| PG | Parental Guidance Suggested: Parents urged to give “parental guidance.” May contain some material parents might not like for their young children. |

| PG–13 | Parents Strongly Cautioned: Parents are urged to be cautious. Some material may be inappropriate for pre- |

| R | Restricted: Contains some adult material. Parents are urged to learn more about the film before taking their young children with them. |

| NC–17 | No one 17 and under admitted: Clearly adult. Children are not admitted. |

Table 16.1: TABLE 16.1 THE VOLUNTARY MOVIE RATING SYSTEMData from: Motion Picture Association of America, “Understanding the Film Ratings,” accessed November 24, 2014, www.mpaa.org/

The MPAA copyrighted all ratings designations as trademarks except for the X rating, which was gradually appropriated as a promotional tool by the pornographic film industry. In fact, between 1972 and 1989, the MPAA stopped issuing the X rating. In 1990, however, based on protests from filmmakers over movies with adult sexual themes that they did not consider pornographic, the industry copyrighted the NC–17 rating—