The Development of Sound Recording

New mass media have often been defined in terms of the communication technologies that preceded them. For example, movies were initially called motion pictures, a term that derived from photography; radio was known as wireless telegraphy, referring to telegraphs; and television was often called picture radio. Likewise, sound recording instruments were initially described as talking machines and later as phonographs, indicating the existing innovations, the telephone and the telegraph. This early blending of technology foreshadowed our contemporary era, in which media as diverse as newspapers and movies converge on the Internet. Long before the Internet, however, the first major media convergence involved the relationship between the sound recording and radio industries.

From Cylinders to Disks: Sound Recording Becomes a Mass Medium

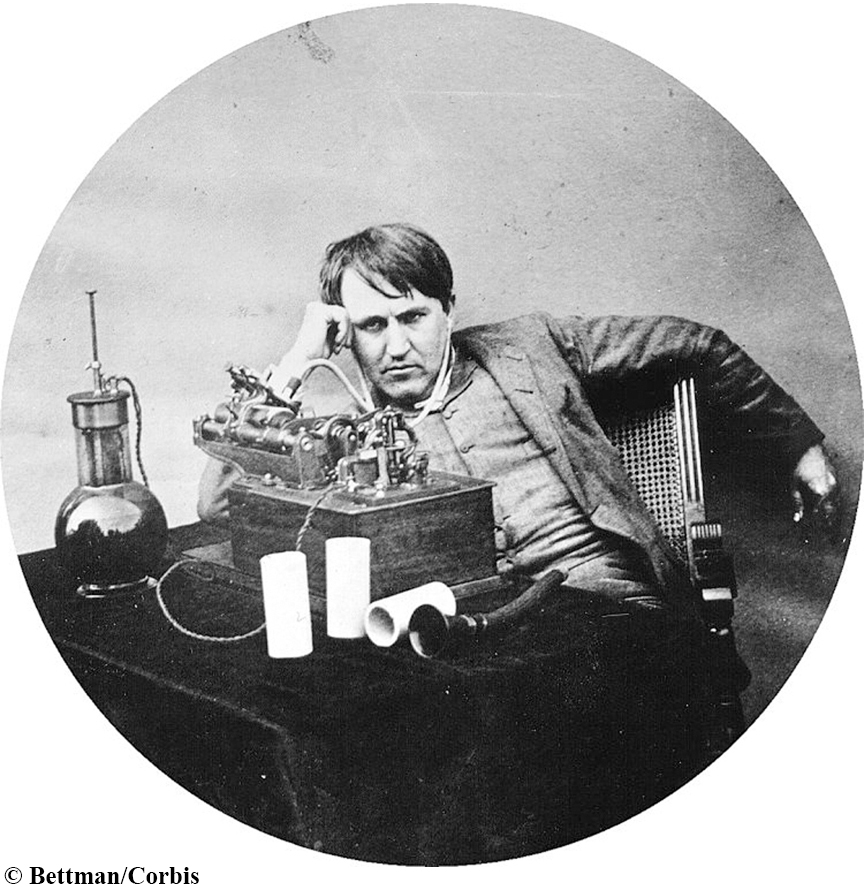

THOMAS EDISON In addition to inventing the phonograph, Edison (1847–1931) ran an industrial research lab that is credited with inventing the motion picture camera, the first commercially successful lightbulb, and a system for distributing electricity.

In the 1850s, the French printer Édouard-

In 1877, Thomas Edison had success playing back sound. He recorded his own voice by using a needle to press his voice’s sound waves onto tinfoil wrapped around a metal cylinder about the size of a cardboard toilet-

Thomas Edison was more than an inventor—

Sound Recording and Popular Music

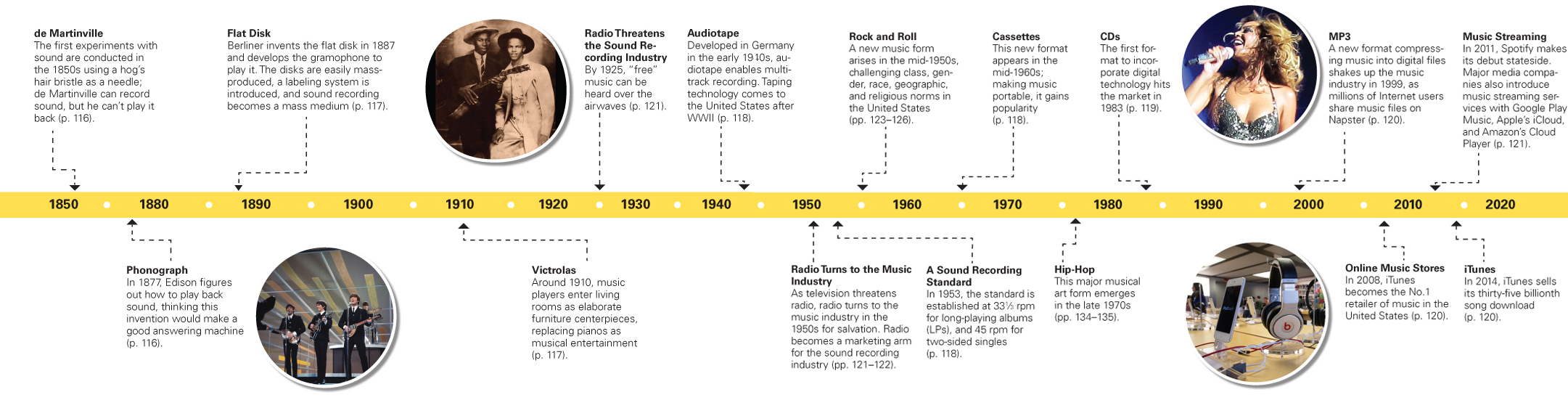

Using ideas from Edison, Bell, and Tainter, Emile Berliner, a German engineer who had immigrated to America, developed a better machine that played round, flat disks, or records. Made of zinc and coated with beeswax, these records played on a turntable, which Berliner called a gramophone and patented in 1887. Berliner also developed a technique that enabled him to mass-

By the first decade of the twentieth century, record-

The appeal of recorded music was limited at first because of sound quality. The original wax records were replaced by shellac discs, but these records were also very fragile and didn’t improve the sound quality much. By the 1930s, in part because of the advent of radio and in part because of the Great Depression, record and phonograph sales declined dramatically. However, in the early 1940s, shellac was needed for World War II munitions production, so the record industry turned to manufacturing polyvinyl plastic records instead. The vinyl recordings turned out to be more durable than shellac records and less noisy, paving the way for a renewed consumer desire to buy recorded music.

In 1948, CBS Records introduced the 33![]() -rpm (revolutions per minute) long-

-rpm (revolutions per minute) long-

From Phonographs to CDs: Analog Goes Digital

The inventions of the phonograph and the record were the key sound recording advancements until the advent of magnetic audiotape and tape players in the 1940s. Magnetic tape sound recording was first developed as early as 1929 and further refined in the 1930s, but it didn’t catch on initially because the first machines were bulky reel-

Audiotape’s lightweight magnetized strands finally made possible sound editing and multiple-

Some thought the portability, superior sound, and recording capabilities of audiotape would mean the demise of records. Although records had retained essentially the same format since the advent of vinyl, the popularity of records continued, in part due to the improved sound fidelity that came with stereophonic sound. Invented in 1931 by engineer Alan Blumlein but not put to commercial use until 1958, stereo permitted the recording of two separate channels, or tracks, of sound. Recording-

The biggest recording advancement came in the 1970s, when electrical engineer Thomas Stockham made the first digital audio recordings on standard computer equipment. Although the digital recorder was invented in 1967, Stockham was the first to put it to practical use. In contrast to analog recording, which captures the fluctuations of sound waves and stores those signals in a record’s grooves or a tape’s continuous stream of magnetized particles, digital recording translates sound waves into binary on-

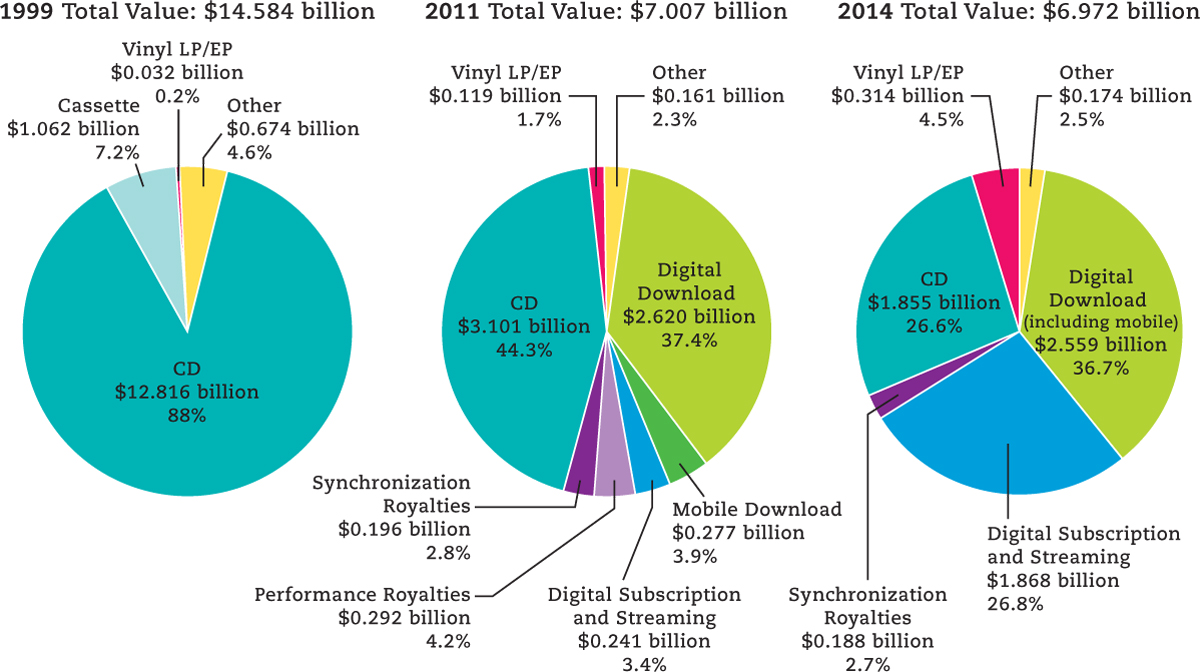

FIGURE 4.1THE EVOLUTION OF DIGITAL SOUND RECORDING SALES (REVENUE IN BILLIONS)Data from: Recording Industry Association of America, Annual Year-

By 1987, CD sales were double the amount of LP record album sales. By 2000, CDs rendered records and audiocassettes nearly obsolete, except for DJs and record enthusiasts who continued to play and collect vinyl LPs. In an effort to create new product lines and maintain consumer sales, the music industry promoted two advanced digital disc formats in the late 1990s, which it hoped would eventually replace standard CDs. However, the introduction of these formats was ill-

Convergence: Sound Recording in the Internet Age

Music, perhaps more so than any other mass medium, is bound up in the social fabric of our lives. Ever since the introduction of the tape recorder and the heyday of homemade mixtapes, music has been something that we have shared eagerly with friends.

It is not surprising, then, that the Internet, a mass medium that links individuals and communities together like no other medium, became a hub for sharing music. In fact, the reason college student Shawn Fanning said he developed the groundbreaking file-

MP3s and File-

The MP3 file format, developed in 1992, enables digital recordings to be compressed into smaller, more manageable files. With the increasing popularity of the Internet in the mid-

By 1999, the year Napster’s infamous free file-

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the music industry and against Napster, declaring free music file-

The recording industry fought back with thousands of lawsuits, many of them successful. In 2005, P2P service Grokster shut down after it was fined $50 million by U.S. federal courts, and in upholding the lower court rulings, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that the music industry could pursue legal action against any P2P service that encouraged its users to illegally share music or other media. By 2010, eDonkey, Morpheus, and LimeWire had been shut down, while Kazaa settled a lawsuit with the music industry and became a legal service.11 By 2011, several major Internet service providers, including AT&T, Cablevision, Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon, agreed to help the music industry identify customers who may be illegally downloading music and try to prevent them from doing so by sending them “copyright alert” warning letters, redirecting them to Web pages about digital piracy, and ultimately slowing download speeds or closing their broadband accounts.

BEATS BY DR. DRE headphones became the must-

As it cracked down on digital theft, the music industry also realized that it would have to somehow adapt its business to the digital format and embraced services like iTunes (launched by Apple in 2003 to accompany the iPod), which has become the model for legal online distribution. In 2008, iTunes became the top music retailer in the United States, and by 2013, iTunes had sold more than twenty-

The Next Big Thing: Streaming Music

SPOTIFY became popular in Europe before the streaming service made its U.S. debut in 2011. Now available in more than fifty-

If the history of recorded music tells us anything, it’s that over time tastes change and formats change. The digital music era began in 1983 with the debut of the CD. Next was the digital download, made a commercially viable option by iTunes in 2003. Today, streaming music is quickly growing in popularity. In the language of the music industry, we are shifting from ownership of music to access to music.13 The access model has been driven by the availability of streaming services such as the Sweden-

The Rocky Relationship between Records and Radio

Some streaming services, like Pandora, closely resemble commercial radio; the recording industry and radio have always been closely linked. Although they work almost in unison now, in the beginning they had a tumultuous relationship. Radio’s very existence sparked the first battle. By 1915, the phonograph had become a popular form of entertainment. The recording industry sold thirty million records that year, and by the end of the decade, sales more than tripled each year. In 1924, though, record sales dropped to only half of what they had been the previous year. Why? Because radio had arrived as a competing mass medium, providing free entertainment over the airwaves, independent of the recording industry.

The battle heated up when, to the alarm of the recording industry, radio stations began broadcasting recorded music without compensating the music industry. The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP), founded in 1914 to collect copyright fees for music publishers and writers, charged that radio was contributing to plummeting sales of records and sheet music. By 1925, ASCAP established music rights fees for radio, charging stations between $250 and $2,500 a week to play recorded music—

But other stations countered by establishing their own live, in-

The recording and radio industries only began to cooperate with each other after television became popular in the early 1950s. Television pilfered radio’s variety shows, crime dramas, and comedy programs, and, along with those formats, much of its advertising revenue and audience. Seeking to reinvent itself, radio turned to the recording industry, and this time both industries greatly benefited from radio’s new “hit songs” format. The alliance between the recording industry and radio was aided enormously by rock-

After the digital turn, that mutually beneficial arrangement between the recording and radio industries began to fray. While Internet streaming radio stations were being required to pay royalties to music companies when they played their songs, radio stations still got to play music royalty-