The Evolution of Radio

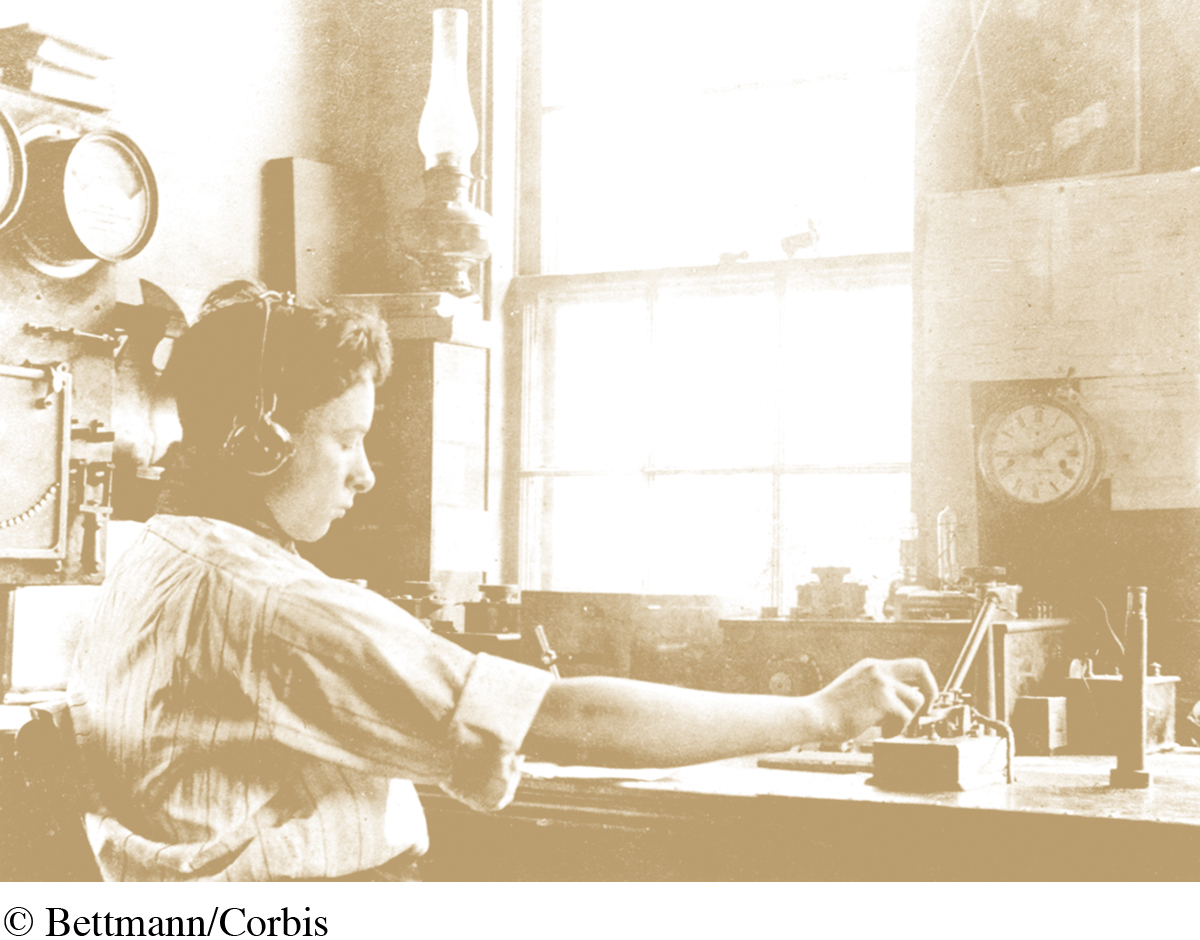

When Westinghouse engineer Frank Conrad set up a crude radio studio above his Pittsburgh garage in 1916, placing a microphone in front of a phonograph to broadcast music and news to his friends (whom Conrad supplied with receivers) two evenings a week on experimental station 8XK, he unofficially became one of the medium’s first disc jockeys. In 1920, a Westinghouse executive, intrigued by Conrad’s curious hobby, realized the potential of radio as a mass medium. Westinghouse then established station KDKA, which is generally regarded as the first commercial broadcast station. KDKA is most noted for airing national returns from the Cox–Harding presidential election on November 2, 1920, an event most historians consider the first professional broadcast.

Other amateur broadcasters could also lay claim to being first. One of the earliest stations, operated by Charles “Doc” Herrold in San Jose, California, began in 1909 and later became KCBS. Additional experimental stations—

In 1921, the U.S. Commerce Department officially licensed five radio stations for operation; by early 1923, more than six hundred commercial and noncommercial stations were operating. Some stations were owned by AT&T, GE, and Westinghouse, but many were run by amateurs or were independently owned by universities or businesses. By the end of 1923, as many as 550,000 radio receivers, most manufactured by GE and Westinghouse, had been sold for about $55 each (about $701 in today’s dollars). Just as the “guts” of the phonograph had been put inside a piece of furniture to create a consumer product, the vacuum tubes, electrical posts, and bulky batteries that made up the radio receiver were placed inside stylish furniture and marketed to households. By 1925, 5.5 million radio sets were in use across America, and radio was officially a mass medium.

Building the First Networks

WESTINGHOUSE ENGINEER FRANK CONRAD Broadcasting from his garage, Conrad’s hobby became Pittsburgh’s KDKA, one of the first radio stations. Although this early station is widely celebrated in history books as the first broadcasting outlet, one can’t underestimate the influence Westinghouse had in promoting this “historical first.” Westinghouse clearly saw the celebration of Conrad’s garage studio as a way to market the company and its radio equipment. The resulting legacy of Conrad’s garage studio has thus overshadowed other individuals who also experimented with radio broadcasting.

In a major power grab in 1922, AT&T, which already had a government-

In the same year, AT&T started WEAF (now WNBC) in New York, the first radio station to regularly sell commercial time to advertisers. AT&T claimed that under the RCA agreements it had the exclusive right to sell ads, which AT&T called toll broadcasting. Most people in radio at the time recoiled at the idea of using the medium for crass advertising, viewing it instead as a public information service. In fact, stations that had earlier tried to sell ads received “cease and desist” letters from the Department of Commerce. But by August 1922, AT&T had nonetheless sold its first ad to a New York real estate developer for $50. The idea of promoting the new medium as a public service, along the lines of today’s noncommercial National Public Radio (NPR), ended when executives realized that radio ads offered another opportunity for profits long after radio-

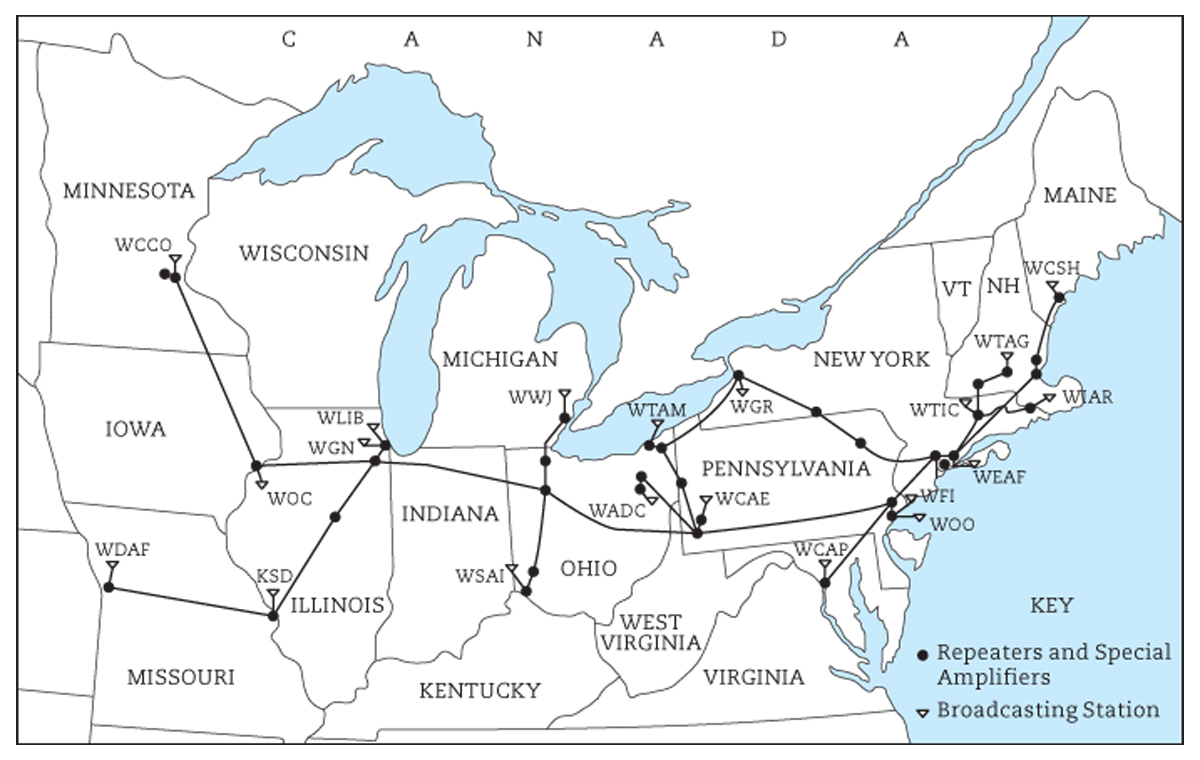

The initial strategy behind AT&T’s toll broadcasting idea was an effort to conquer radio. By its agreements with RCA, AT&T retained the rights to interconnect the signals between two or more radio stations via telephone wires. In 1923, when AT&T aired a program simultaneously on its flagship WEAF station and on WNAC in Boston, the phone company created the first network: a cost-

DAVID SARNOFF As a young man, Sarnoff taught himself Morse code and learned as much as possible in Marconi’s experimental shop in New York. He was then given a job as wireless operator for the station on Nantucket Island. He went on to create NBC and network radio. Sarnoff’s calculated ambition in the radio industry can easily be compared to Bill Gates’s drive to control the computer software and Internet industries.

In response, GE, Westinghouse, and RCA interconnected a smaller set of competing stations, known as the radio group. Initially, their network linked WGY in Schenectady, New York (then GE’s national headquarters), and WJZ in Manhattan. The radio group had to use inferior Western Union telegraph lines when AT&T denied them access to telephone wires. By this time, AT&T had sold its stock in RCA and refused to lease its lines to competing radio networks. The telephone monopoly was now enmeshed in a battle to defeat RCA for control of radio.

This clash, among other problems, eventually led to a government investigation and an arbitration settlement in 1925. In the agreement, the Justice Department, irritated by AT&T’s power grab, redefined patent agreements. AT&T received a monopoly on providing the wires, known as long lines, to interconnect stations nationwide. In exchange, AT&T sold its BCA network to RCA for $1 million and agreed not to reenter broadcasting for eight years (a banishment that actually extended into the 1990s).

Sarnoff and NBC: Building the “Blue” and “Red” Networks

After Lee De Forest, David Sarnoff was among the first to envision wireless telegraphy as a modern mass medium. From the time he served as Marconi’s personal messenger (at age fifteen), Sarnoff rose rapidly at American Marconi. He became a wireless operator, helping relay information about the Titanic survivors in 1912. Promoted to a series of management positions, Sarnoff was closely involved in RCA’s creation in 1919, when most radio executives saw wireless merely as point-

NBC’S RED NETWORK was formed by RCA in 1926. WEAF, the first station in New York, was the Red network’s flagship station.

After RCA bought AT&T’s telephone group network (BCA), Sarnoff created a new subsidiary in September 1926 called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). Its ownership was shared by RCA (50 percent), General Electric (30 percent), and Westinghouse (20 percent). This loose network of stations would be hooked together by AT&T long lines. Shortly thereafter, the original telephone group became known as the NBC-

Although NBC owned a number of stations by the late 1920s, many independent stations also began affiliating with the NBC networks to receive programming. NBC affiliates, though independently owned, signed contracts to be part of the network and paid NBC to carry its programs. In exchange, NBC reserved time slots, which it sold to national advertisers. NBC centralized costs and programming by bringing the best musical, dramatic, and comedic talent to one place, where programs could be produced and then distributed all over the country. By 1933, NBC-

Network radio may have actually helped modernize America by de-

David Sarnoff’s leadership at RCA was capped by two other negotiations that solidified his stature as the driving force behind radio’s development as a modern medium: cutting a deal with General Motors for the manufacture of car radios (under the brand name Motorola) in 1929, and merging RCA with the Victor Talking Machine Company. Afterward, until the mid-

Government Scrutiny Ends RCA-

As early as 1923, the Federal Trade Commission had charged RCA with violations of antitrust laws, but the FTC allowed the monopoly to continue. By the late 1920s, the government, concerned about NBC’s growing control over radio content, intensified its scrutiny. Then, in 1930, federal marshals charged RCA-

RCA acted quickly. To eliminate its monopolizing partnerships, Sarnoff’s company proposed buying out GE’s and Westinghouse’s remaining shares in RCA’s manufacturing business. Now RCA would compete directly against GE, Westinghouse, and other radio manufacturers, encouraging more competition in the radio manufacturing industry. In 1932, days before the antitrust case against RCA was to go to trial, the government accepted RCA’s proposal for breaking up its monopoly. Ironically, in the mid-

CBS and Paley: Challenging NBC

CBS HELPED ESTABLISH ITSELF as a premier radio network by attracting top talent from NBC, like comedic duo George Burns and Gracie Allen. They first brought their “Dumb Dora” and straight man act from stage to radio in 1929, and then continued on various radio programs in the 1930s and 1940s, with the most well known being The Burns and Allen Show. CBS also reaped the benefits when Burns and Allen moved their eponymous show to television in 1950.

Even with RCA’s head start and its favored status, the two NBC networks faced competitors in the late 1920s. The competitors, however, all found it tough going. One group, United Independent Broadcasters (UIB), even lined up twelve prospective affiliates and offered them $500 a week for access to ten hours of station time in exchange for quality programs. UIB was cash-

Enter the Columbia Phonograph Company, which was looking for a way to preempt RCA’s merger with the Victor Company, then the record company’s major competitor. With backing from Columbia, UIB launched the new Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System (CPBS), a wobbly sixteen-

In 1928, William Paley, the twenty-

By 1933, Paley’s efforts had netted CBS more than ninety affiliates, many of them defecting from NBC. Paley also concentrated on developing news programs and entertainment shows, particularly soap operas and comedy-

Bringing Order to Chaos with the Radio Act of 1927

In the 1920s, as radio moved from narrowcasting to broadcasting, the battle for more frequency space and less channel interference intensified. Manufacturers, engineers, station operators, network executives, and the listening public demanded action. Many wanted more sweeping regulation than the simple licensing function granted under the Radio Act of 1912, which gave the Commerce Department little power to deny a license or to unclog the airwaves.

Beginning in 1924, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover ordered radio stations to share time by setting aside certain frequencies for entertainment and news, and others for farm and weather reports. To challenge Hoover, a station in Chicago jammed the airwaves, intentionally moving its signal onto an unauthorized frequency. In 1926, the courts decided that based on the existing Radio Act, Hoover had the power only to grant licenses, not to restrict stations from operating. Within the year, two hundred new stations clogged the airwaves, creating a chaotic period in which nearly all radios had poor reception. By early 1927, sales of radio sets had declined sharply.

To restore order to the airwaves, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927, which stated an extremely important principle—

In 1941, an activist FCC went after the networks. Declaring that NBC and CBS could no longer force affiliates to carry programs they did not want, the government outlawed the practice of option time, which Paley had used to build CBS into a major network. The FCC also demanded that RCA sell one of its two NBC networks. RCA and NBC claimed that the rulings would bankrupt them. The Supreme Court sided with the FCC, however, and RCA eventually sold NBC-

| Act | Provisions | Effects |

| Wireless Ship Act of 1910 | Required U.S. seagoing ships carrying more than fifty passengers and traveling more than two hundred miles off the coast to be equipped with wireless equipment with a one- |

Saved lives at sea, including more than seven hundred rescued by ships responding to the Titanic’s distress signals two years later. |

| Radio Act of 1912 | Required radio operators to obtain a license, gave the Commerce Department the power to deny a license, and began a uniform system of assigning call letters to identify stations. | The federal government began to assert control over radio. Penalties were established for stations that interfere with other stations’ signals. |

| Radio Act of 1927 | Established the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) as a temporary agency to oversee licenses and negotiate channel assignments. | First expressed the now- |

| Communications Act of 1934 | Established the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to replace the FRC. The FCC regulated radio; the telephone; the telegraph; and later television, cable, and the Internet. | Congress tacitly agreed to a system of advertising- |

| Telecommunications Act of 1996 | Eliminated most radio and television station ownership rules, some dating back more than fifty years. | Enormous national and regional station groups formed, dramatically changing the sound and localism of radio in the United States. |

Table 5.1: TABLE 5.1 MAJOR ACTS IN THE HISTORY OF U.S. RADIO

The Golden Age of Radio

Many programs on television today were initially formulated for radio. The first weather forecasts and farm reports on radio began in the 1920s. Regularly scheduled radio news analysis started in 1927, with H. V. Kaltenborn, a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle, providing commentary on AT&T’s WEAF. The first regular network news analysis began on CBS in 1930 and featured Lowell Thomas, who would remain on radio for forty-

Early Radio Programming

Early on, only a handful of stations operated in most large radio markets, and popular stations were affiliated with CBS, NBC-

Among the most popular early programs on radio, the variety show was the forerunner to popular TV shows like the Ed Sullivan Show. The variety show, developed from stage acts and vaudeville, began with the Eveready Hour in 1923 on WEAF. Considered experimental, the program presented classical music, minstrel shows, comedy sketches, and dramatic readings. Stars from vaudeville, musical comedy, and New York theater and opera would occasionally make guest appearances.

By the 1930s, studio-

Dramatic programs, mostly radio plays that were broadcast live from theaters, developed as early as 1922. Historians mark the appearance of Clara, Lu, and Em on WGN in 1931 as the first soap opera. One year later, Colgate-

Most radio programs had a single sponsor that created and produced each show. The networks distributed these programs live around the country, charging the sponsors advertising fees. Many shows—

Radio Programming as a Cultural Mirror

The situation comedy, a major staple of TV programming today, began on radio in the mid-

Amos ’n’ Andy also launched the idea of the serial show: a program that featured continuing story lines from one day to the next. The format was soon copied by soap operas and other radio dramas. Amos ’n’ Andy aired six nights a week from 7:00 to 7:15 P.M. During the show’s first year on the network, radio-

FIRESIDE CHATS This giant bank of radio network microphones makes us wonder today how President Franklin D. Roosevelt managed to project such an intimate and reassuring tone in his famous fireside chats. Conceived originally to promote FDR’s New Deal policies amid the Great Depression, these chats were delivered between 1933 and 1944 and touched on topics of national interest. Roosevelt was the first president to effectively use broadcasting to communicate with citizens; he also gave nearly a thousand press conferences during his twelve-

The Authority of Radio

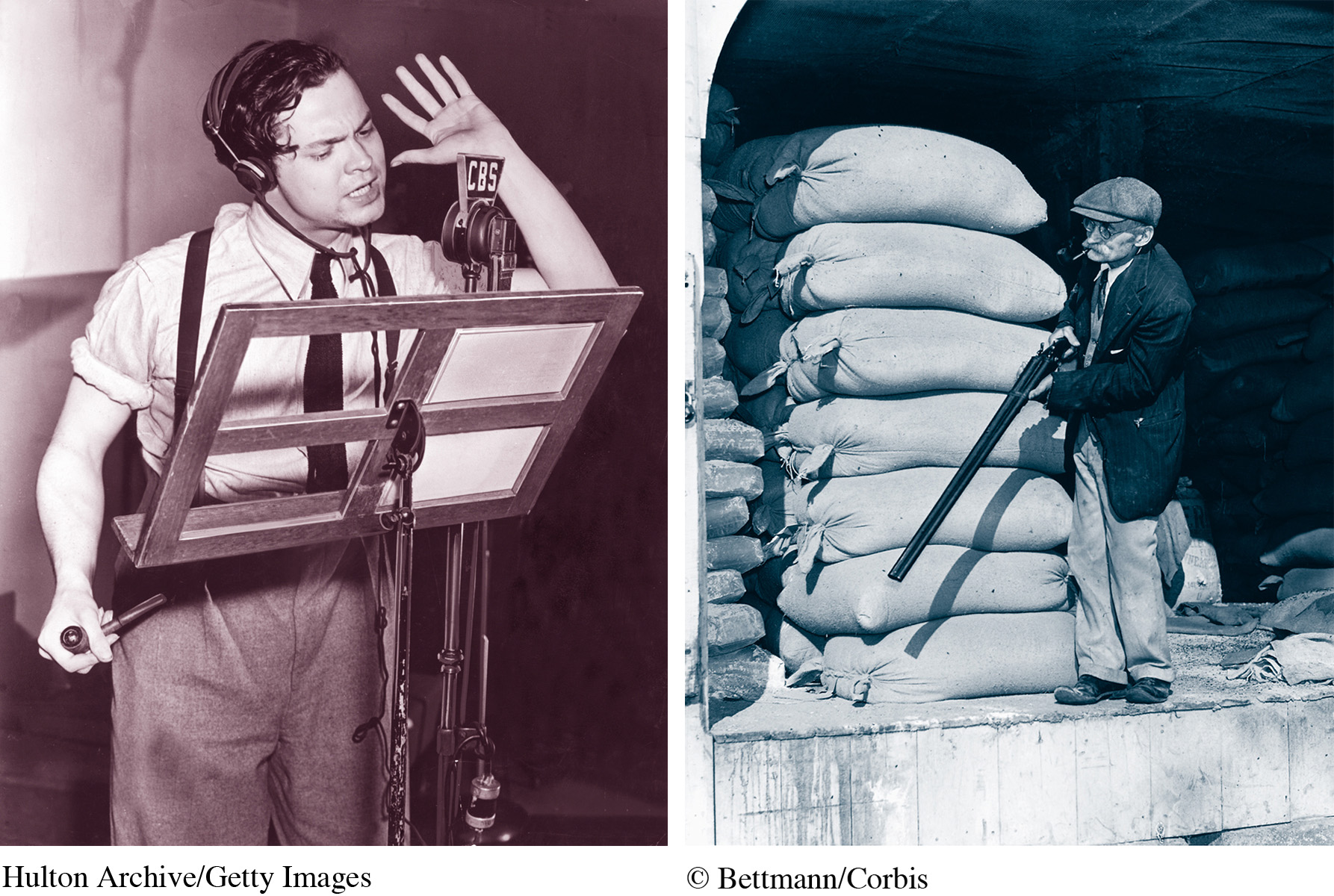

The most famous single radio broadcast of all time was an adaptation of H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds on the radio series Mercury Theater of the Air. Orson Welles produced, hosted, and acted in this popular series, which adapted science fiction, mystery, and historical adventure dramas for radio. On Halloween eve in 1938, the twenty-

EARLY RADIO’S EFFECT AS A MASS MEDIUM On Halloween eve in 1938, Orson Welles’s radio dramatization of War of the Worlds (far left) created a panic up and down the East Coast, especially in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey—

The program created a panic that lasted several hours. In New Jersey, some people walked through the streets with wet towels around their heads for protection from deadly Martian heat rays. In New York, young men reported to their National Guard headquarters to prepare for battle. Across the nation, calls jammed police switchboards. Afterward, Orson Welles, once the radio voice of The Shadow, used the notoriety of this broadcast to launch a film career. Meanwhile, the FCC called for stricter warnings both before and during programs that imitated the style of radio news.