Technology and Convergence Change Viewing Habits

LaunchPad

Television Networks Evolve Insiders discuss how cable and satellite have changed the television market.

Discussion: How might definitions of a TV network change in the realm of new digital media?

Among the biggest technical innovations in TV viewing are nontelevision delivery systems. We can skip a network broadcast and still watch our favorite shows on DVRs, laptops, or mobile devices for free or for a nominal cost. Not only is TV being reinvented, but its audiences—

200

Home Video

In 1975–76, the consumer introduction of videocassettes and videocassette recorders (VCRs) enabled viewers to tape-

VCRs also got a boost from a failed suit brought against Sony by Disney and MCA (now NBC Universal) in 1976: The two film studios alleged that home taping violated their movie copyrights. In 1979, a federal court ruled in favor of Sony and permitted home taping for personal use. In response, the movie studios quickly set up videotaping facilities so that they could rent and sell movies in video stores, which became popular in the early 1980s.

Over time, the VHS format gave way to DVDs. But today the standard DVD is threatened by both the Internet and a consumer market move toward high-

By 2012, more than 50 percent of U.S. homes had DVRs (digital video recorders), which enable users to download specific programs onto the DVR’s computer memory and watch at a later time. While offering greater flexibility for viewers, DVRs also provide a means to “watch” the watchers. DVRs give advertisers information about what each household views, allowing them to target viewers with specific ads when they play back their programs. This kind of technology has raised concerns among some lawmakers and consumer groups over the tracking of personal viewing and buying habits by marketers.

The impact of home video has been enormous. More than 95 percent of American homes today are equipped with either DVD or DVR players, resulting in two major developments: video rentals and time shifting. Video rentals, formerly the province of walk-

The Third Screen: TV Converges with the Internet

The Internet has transformed the way many of us, especially younger generations, watch movies, TV, and cable programming. These new online viewing experiences are often labeled third screens, usually meaning that computer screens are the third major way we view content (movie screens and traditional TV sets are the first and second screens, respectively). By far the most popular site for viewing video online is YouTube. Containing some original shows, classic TV episodes, full-

201

But YouTube has competition from sites that offer full-

In late 2010, Hulu started Hulu Plus, a paid subscription service. For about $8 a month, viewers can stream full seasons of current and older programs and some movies and documentaries on their computer, TV, or mobile device. Hulu Plus had more than 6 million subscribers by 2014, up from 2 million in early 2012. HBO Now, a stand-

In addition, cable TV giants like Comcast and Time Warner are making programs available to download or stream through sites like Xfinity TV and TV Everywhere. These programs are open only to subscribers, who can download cable TV shows using a password and username. In 2012, Netflix, looking to increase its subscriber base, started talks with some of the largest U.S. cable operators about adding Netflix as part of their cable packages. However, cable and DBS companies are thus far resisting Netflix’s proposition and rolling out their own video-

In most cases, these third-

202

Fourth Screens: Smartphones and Mobile Video

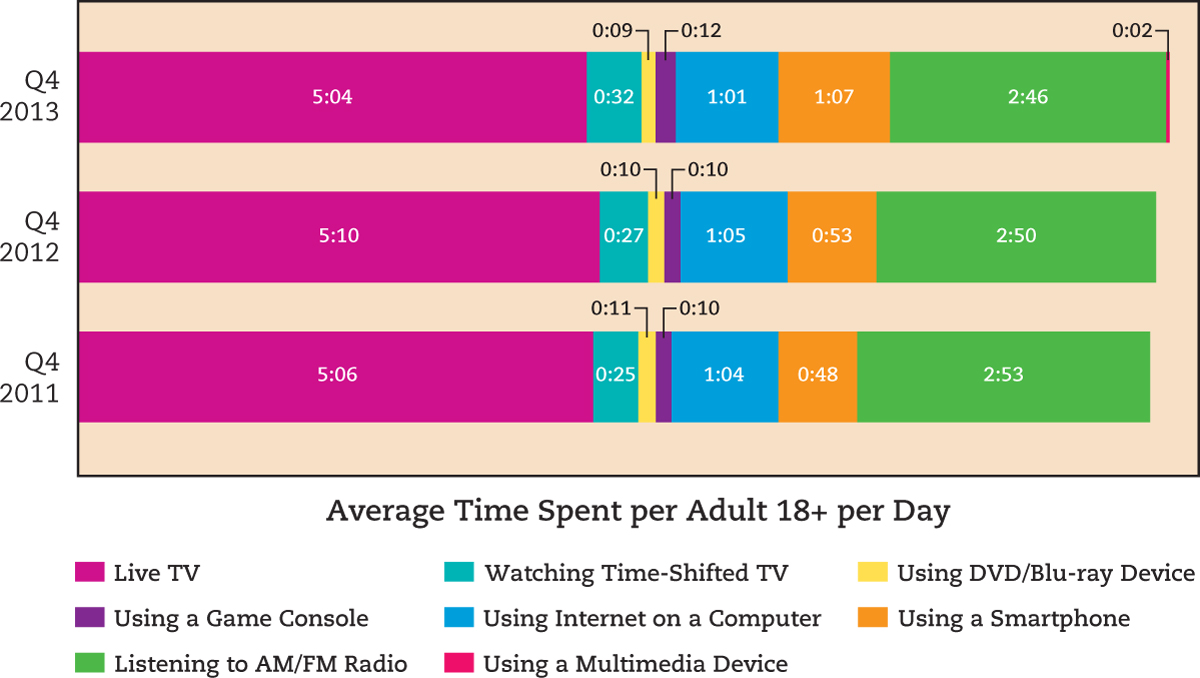

According to Nielsen’s 2014 “Digital Consumer” report, 84 percent of smartphone and tablet owners said they used those devices as an additional screen while watching television “at the same time.”8 Such multitasking has further accelerated with new fourth-

The multifunctionality and portability of third-

203