The Economics and Ownership of Television and Cable

It is not much of a stretch to define TV programming as a system that mostly delivers viewers to merchandise displayed in blocks of ads. And with more than $60 billion at stake in advertising revenues each year, networks and cable services work hard to attract the audiences and subscribers that bring in the advertising dollars. But although broadcast and cable advertising have declined in prominence, one recent study reported that more than 80 percent of consumers say that TV advertising—

217

Production

The key to the TV industry’s success is offering programs that viewers will habitually watch each week—

Production costs generally fall into two categories: below-

Most prime-

Because of smaller audiences and fewer episodes per season, costs for original programs on cable channels are lower than those for network broadcasts.22 In 2012–13, cable channels paid an average of about $1 million per episode in licensing fees to production companies. Some cable shows, like AMC’s Breaking Bad, cost about $3 million per episode, but since cable seasons are shorter (usually ten to thirteen episodes per season, compared to twenty-

Still, both networks and cable channels build up deficits. This is where film studios like Disney, Sony, and Twentieth (now 21st) Century Fox have been playing a crucial role: They finance the deficit and hope to profit on lucrative deals when the show—

218

To save money and control content, many networks and cable stations create programs that are less expensive than sitcoms and dramas. These include TV newsmagazines and reality programs. For example, NBC’s Dateline requires only about half the outlay (between $700,000 and $900,000 per episode) demanded by a new hour-

Distribution

Programs are paid for in a variety of ways. Cable service providers (e.g., Time Warner Cable or Cablevision) rely mostly on customer subscriptions to pay for distributing their channels, but they also have to pay the broadcast networks retransmission fees to carry network channels and programming. While broadcast networks do earn carriage fees from cable and DBS providers, they pay affiliate stations license fees to carry their programs. In return, the networks sell the bulk of advertising time to recoup their fees and their investments in these programs. In this arrangement, local stations receive national programs that attract large local audiences and are allotted some local ad time to sell during the programs to generate their own revenue.

A common misconception is that TV networks own their affiliated stations. This is not usually true. Although traditional networks like NBC own stations in major markets like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, throughout most of the country networks sign short-

Although a local affiliate typically carries a network’s entire lineup, a station may substitute a network’s program. According to clearance rules established in the 1940s by the Justice Department and the FCC, all local affiliates are ultimately responsible for the content of their channels and must clear, or approve, all network programming. Over the years, some of the circumstances in which local affiliates have rejected a network’s programming have been controversial. For example, in 1956 singer Nat King Cole was one of the first African American performers to host a network variety program. As a result of pressure applied by several white southern organizations, though, the program had trouble attracting a national sponsor. When some affiliates, both southern and northern, refused to carry the program, NBC canceled it in 1957. More recently, affiliates may occasionally substitute other programming for network programs they think may offend their local audiences, especially if the programs contain excessive violence or explicit sexual content.

Syndication Keeps Shows Going and Going . . .

Syndication—leasing TV stations or cable networks the exclusive right to air TV shows—

Syndication plays a large role in programming for both broadcast and cable networks. For local network-

219

Types of Syndication

In off-

First-

Barter versus Cash Deals

Most financing of television syndication is either a cash deal or a barter deal. In a cash deal, the distributor offers a series for syndication to the highest bidder. Because of exclusive contractual arrangements, programs air on only one broadcast outlet per city in a major TV market or, in the case of cable, on one cable channel’s service across the country. Whoever bids the most gets to syndicate the program (which can range from a few thousand dollars for a week’s worth of episodes in a small market to $250,000 a week in a large market). In a variation of a cash deal called cash-

Although syndicators prefer cash deals, barter deals are usually arranged for new, untested, or older but less popular programs. In a straight barter deal, no money changes hands. Instead, a syndicator offers a program to a local TV station in exchange for a split of the advertising revenue. For example, in a 7/5 barter deal, during each airing the show’s producers and syndicator retain seven minutes of ad time for national spots and leave stations with five minutes of ad time for local spots. As programs become more profitable, syndicators repackage and lease the shows as cash-

220

Measuring Television Viewing

Primarily, TV shows live or die based on how satisfied advertisers are with the quantity and quality of the viewing audience. Since 1950, the major organization that tracks and rates prime-

The Impact of Ratings and Shares on Programming

In TV measurement, a rating is a statistical estimate expressed as the percentage of households that are tuned to a program in the market being sampled. Another audience measure is the share, a statistical estimate of the percentage of homes that are tuned to a specific program compared with those using their sets at the time of the sample. For instance, let’s say on a typical night that 5,000 metered homes are sampled by Nielsen in 210 large U.S. cities, and 4,000 of those households have their TV sets turned on. Of those 4,000, about 1,000 are tuned to The Voice on NBC. The rating for that show is 20 percent—

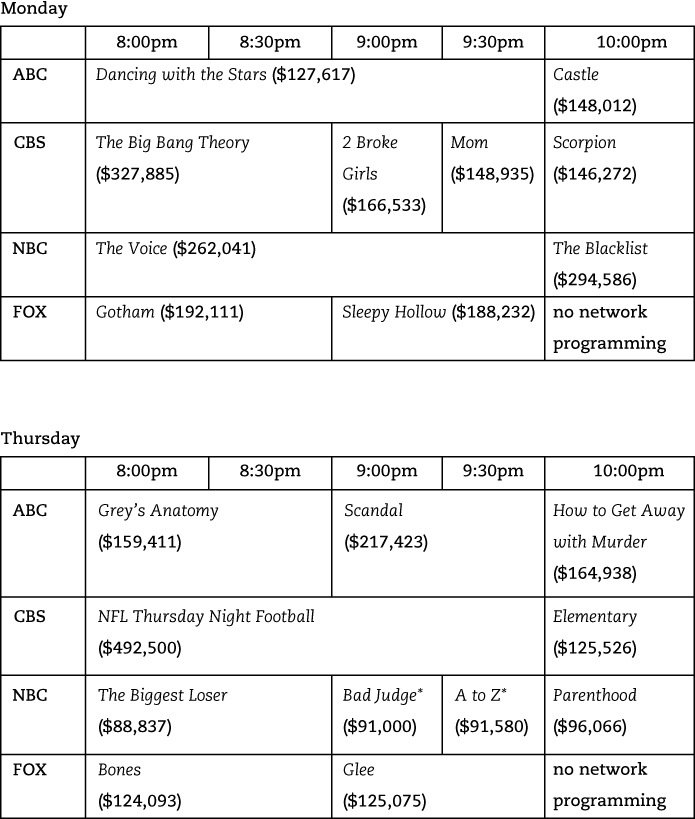

The importance of ratings and shares to the survival of TV programs cannot be overestimated. In practice, television is an industry in which networks, producers, and distributors target, guarantee, and “sell” viewers in blocks to advertisers. Audience measurement tells advertisers not only how many people are watching but, more important, what kinds of people are watching. Prime-

Assessing Today’s Converged and Multiscreen Markets

During the height of the network era, a prime-

221

| Program | Network | Date | Rating | |

| 1 | M*A*S*H (final episode) | CBS | 2/28/83 | 60.2 |

| 2 | Dallas (“Who Shot J.R.?” episode) | CBS | 11/21/80 | 53.3 |

| 3 | The Fugitive (final episode) | ABC | 8/29/67 | 45.9 |

| 4 | Cheers (final episode) | NBC | 5/20/93 | 45.5 |

| 5 | Ed Sullivan Show (Beatles’ first U.S. TV appearance) | CBS | 2/9/64 | 45.3 |

| 6 | Beverly Hillbillies | CBS | 1/8/64 | 44.0 |

| 7 | Ed Sullivan Show (Beatles’ second U.S. TV appearance) | CBS | 2/16/64 | 43.8 |

| 8 | Beverly Hillbillies | CBS | 1/15/64 | 42.8 |

| 9 | Beverly Hillbillies | CBS | 2/26/64 | 42.4 |

| 10 | Beverly Hillbillies | CBS | 3/25/64 | 42.2 |

In its efforts to keep up with TV’s move to smaller screens, Nielsen is also using special software to track TV viewing on computers and mobile devices. Today, with the fragmentation of media audiences, the increase in third-

The biggest revenue game changer in the small-

The way advertising works online differs substantially from the way it works on network TV, where advertisers pay as much as $400,000 to buy one thirty-

222

TRACKING TECHNOLOGY

Binging Gives TV Shows a Second Chance—

T raditional broadcast networks like Fox and NBC have been slow to understand or adapt to how TV viewers today—

In an article for Wired magazine, cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken tried to answer the “why we binge-

But then, as cultural anthropologists do, he dug deeper: “So much of contemporary culture leaves the station without us; binging is a way to climb aboard . . . and get back in touch with culture outside the constraints of time. Binge-

McCracken argues that TV binging is partly about making reality “go away” in order to build a refuge from everyday life. “The second screen,” he says, “in some ways becomes our second home.” Then by drawing our friends and family into a particular series and the binging ritual, “we can make that world—

223

The Major Programming Corporations

After deregulation began in the 1980s, many players in TV and cable consolidated to broaden their offerings, expand their market share, and lower expenses. For example, Disney now owns both ABC and ESPN and can spread the costs of sports programming over its networks and its various ESPN cable channels. This business strategy has produced an oligopoly in which just a handful of media corporations now controls programming.

The Major Broadcast Networks

Despite their declining reach and the rise of cable, the traditional networks have remained attractive business investments. In 1985, General Electric, which once helped start RCA-

To combat audience erosion in the 1990s, the major networks began acquiring or developing cable channels to recapture viewers. Thus what appears to be competition between TV and cable is sometimes an illusion. NBC, for example, operates MSNBC, CNBC, and Bravo. ABC owns ESPN along with portions of Lifetime, A&E, and History. However, the networks continue to attract larger audiences than their cable or online competitors. For the 2013–14 season, CBS led the broadcast networks in ratings, followed by NBC, ABC, Fox, Univision, and the CW. CBS averaged over 11 million viewers per evening (while the CW drew about 1.5 million viewers each evening), although NBC reached more of the viewers most cherished by advertisers—

Major Cable and DBS Companies

In the late 1990s, cable became a coveted investment, not so much for its ability to carry television programming as for its access to households connected with high-

In cable, the industry behemoth today is Comcast, especially after its takeover of NBC and move into network broadcasting. Back in 2001, AT&T had merged its cable and broadband industry in a $72 billion deal with Comcast, then the third-

| Rank | Video Subscription Service | Subscribers |

| 1 | Netflix | 41.4 million |

| 2 | Comcast | 22.4 million |

| 3 | DirecTV | 20.4 million |

| 4 | Dish | 14.0 million |

| 5 | Time Warner Cable | 11.0 million |

| 6 | Hulu Plus | 9.0 million |

| 7 | AT&T | 5.9 million |

| 8 | Verizon FiOS | 5.6 million |

| 9 | Charter Communications | 4.3 million |

| 10 | Cox Communications | 4.1 million |

224

In the DBS market, DirecTV and Dish control virtually all the DBS service in the continental United States. In 2008, News Corp. sold DirecTV to cable service provider Liberty Media, which also owned the Encore and Starz movie channels. The independently owned Dish was founded as EchoStar Communications in 1980. In 2014, to counter the proposed merger talks between cable giants Comcast and TWC, DirecTV began investigating deals with both Dish and AT&T. Over the last few years, TV services (combined with existing voice and Internet services) offered by telephone giants AT&T (U-

The Effects of Consolidation

There are some concerns that the trend toward cable, broadcasting, and telephone companies merging will limit expression of political viewpoints, programming options, and technical innovation, and lead to price-

The response from the industries is that, given the tremendous capital investment it takes to run television, cable, and other media enterprises, it is necessary to form business conglomerates in order to buy up struggling companies and keep them afloat. This argument suggests that without today’s video subscription services, many smaller ventures in programming would not be possible. However, there is evidence that large MSOs and other big media companies can wield their monopoly power unfairly. Business disputes have caused disruptions as networks and cable providers have dropped one another from their services, leaving customers in the dark. For example, in October 2010, News Corp. pulled six channels—

225

Alternative Voices

After suffering through years of rising rates and limited expansion of services, some small U.S. cities have decided to challenge the private monopolies of cable giants by building competing, publicly owned cable systems. So far, the municipally owned cable systems number in the hundreds and can be found in places like Glasgow, Kentucky; Kutztown, Pennsylvania; Cedar Falls, Iowa; and Provo, Utah. In most cases, they’re operated by the community-

The first town to take on a national commercial cable provider (Comcast now runs the cable service there) was Glasgow, Kentucky, which built a competing municipal cable system in 1989. The town of fourteen thousand had seven thousand municipal cable customers in 2015. William J. Ray, the town’s Electric Plant Board superintendent and the visionary behind the municipal communications service, has argued that this is not a new idea:

Cities have long been turning a limited number of formerly private businesses into public-

More than a quarter of the country’s two thousand municipal utilities offer broadband services, including cable, high-