Competing Models of Modern Print Journalism

The early commercial and partisan presses were, to some extent, covering important events impartially. These papers often carried verbatim reports of presidential addresses and murder trials, or the annual statements of the U.S. Treasury. In the late nineteenth century, as newspapers pushed for greater circulation, newspaper reporting changed. Two distinct types of journalism emerged: the story-

“Objectivity” in Modern Journalism

As the consumer marketplace expanded during the Industrial Revolution, facts and news became marketable products. Throughout the mid-

Ochs and the New York Times

THE NEW YORK TIMES had established itself as the official paper of record by the 1920s. The Times was the first modern newspaper, gathering information and presenting news in a straightforward way—

The ideal of an impartial, or purely informational, news model was championed by Adolph Ochs, who bought the New York Times in 1896. The son of immigrant German Jews, Ochs grew up in Ohio and Tennessee, where at age twenty-

Partly as a marketing strategy, Ochs offered a distinct contrast to the more sensational Hearst and Pulitzer newspapers: an informational paper that provided stock and real estate reports to businesses, court reports to legal professionals, treaty summaries to political leaders, and theater and book reviews to educated general readers and intellectuals. Ochs’s promotional gimmicks took direct aim at yellow journalism, advertising the Times under the motto “It does not soil the breakfast cloth.” Ochs’s strategy is similar to today’s advertising tactic of targeting upscale viewers and readers who control a disproportionate share of consumer dollars.

With the Hearst and Pulitzer papers capturing the bulk of working-

| Newspaper | 2014 Weekday Circulation (print and digital) |

| 1. USA Today* | 3,255,157 |

| 2. Wall Street Journal | 2,294,093 |

| 3. New York Times | 2,149,012 |

| 4. Orange County Register | 681,512 |

| 5. Los Angeles Times | 673,171 |

| 6. San Jose Mercury News | 581,532 |

| 7. New York Post | 477,314 |

| 8. (New York) Daily News | 456,360 |

| 9. (Long Island, N.Y.) Newsday | 443,362 |

| 10. Washington Post | 436,601 |

Table 8.1: TABLE 8.1 THE NATION’S TEN LARGEST DAILY NEWSPAPERS, 2014Note: Count includes print and digital editions.Data from: Cision, “Top 10 US Daily Newspapers,” June 18, 2014, www.cision.com/

“Just the Facts, Please”

Early in the twentieth century, with reporters adopting a more “scientific” attitude to news-

The story form for packaging and presenting this kind of reporting has been traditionally labeled the inverted-

For much of the twentieth century, the inverted-

Despite the success of the New York Times and other modern papers, the more factual inverted-

Interpretive Journalism

By the 1920s, there was a sense, especially after the trauma of World War I, that the impartial approach to reporting was insufficient for explaining complex national and global conditions. It was partly as a result of “drab, factual, objective reporting,” one news scholar contended, that “the American people were utterly amazed when war broke out in August 1914, as they had no understanding of the foreign scene to prepare them for it.”14

The Promise of Interpretive Journalism

Under the sway of objectivity, modern journalism had downplayed an early role of the partisan press: offering analysis and opinion. But with the world becoming more complex, some papers began to reexplore the analytical function of news. The result was the rise of interpretive journalism, which aims to explain key issues or events and place them in a broader historical or social context. According to one historian, this approach, especially in the 1930s and 1940s, was a viable way for journalism to address “the New Deal years, the rise of modern scientific technology, the increasing interdependence of economic groups at home, and the shrinking of the world into one vast arena for power politics.”15 In other words, journalism took an analytic turn in a world grown more interconnected and complicated.

Noting that objectivity and factuality should serve as the foundation for journalism, by the 1920s editor and columnist Walter Lippmann insisted that the press should do more. He ranked three press responsibilities: (1) “to make a current record”; (2) “to make a running analysis of it”; and (3) “on the basis of both, to suggest plans.”16 Indeed, reporters and readers alike have historically distinguished between informational reports and editorial (interpretive) pieces, which offer particular viewpoints or deeper analyses of the issues. Since the boundary between information and interpretation can be somewhat ambiguous, American papers have traditionally placed news analysis in separate, labeled columns and placed opinion articles on certain pages so that readers do not confuse them with “straight news.” It was during this time that political columns developed to evaluate and provide context for news. Moving beyond the informational and storytelling functions of news, journalists and newspapers began to extend their role as analysts.

Broadcast News Embraces Interpretive Journalism

In a surprising twist, the rise of broadcast radio in the 1930s also forced newspapers to become more analytical in their approach to news. At the time, the newspaper industry was upset that broadcasters took their news directly from papers and wire services. As a result, a battle developed between radio journalism and print news. Although mainstream newspapers tried to copyright the facts they reported and sued radio stations for routinely using newspapers as their main news sources, the papers lost many of these court battles. Editors and newspaper lobbyists argued that radio should be permitted to do only commentary. By conceding this interpretive role to radio, the print press tried to protect its dominion over “the facts.” It was in this environment that radio analysis began to flourish as a form of interpretive news. Lowell Thomas delivered the first daily network analysis for CBS on September 29, 1930, attacking Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. By 1941, twenty regular commentators—

Some print journalists and editors came to believe, however, that interpretive stories, rather than objective reports, could better compete with radio. They realized that interpretation was a way to counter radio’s (and later television’s) superior ability to report breaking news quickly—

Literary Forms of Journalism

By the late 1960s, many people were criticizing America’s major social institutions. Political assassinations, Civil Rights protests, the Vietnam War, the drug culture, and the women’s movement were not easily explained. Faced with so much change and turmoil, many individuals began to lose faith in the ability of institutions to oversee and ensure the social order. Members of protest movements as well as many middle-

Journalism as an Art Form

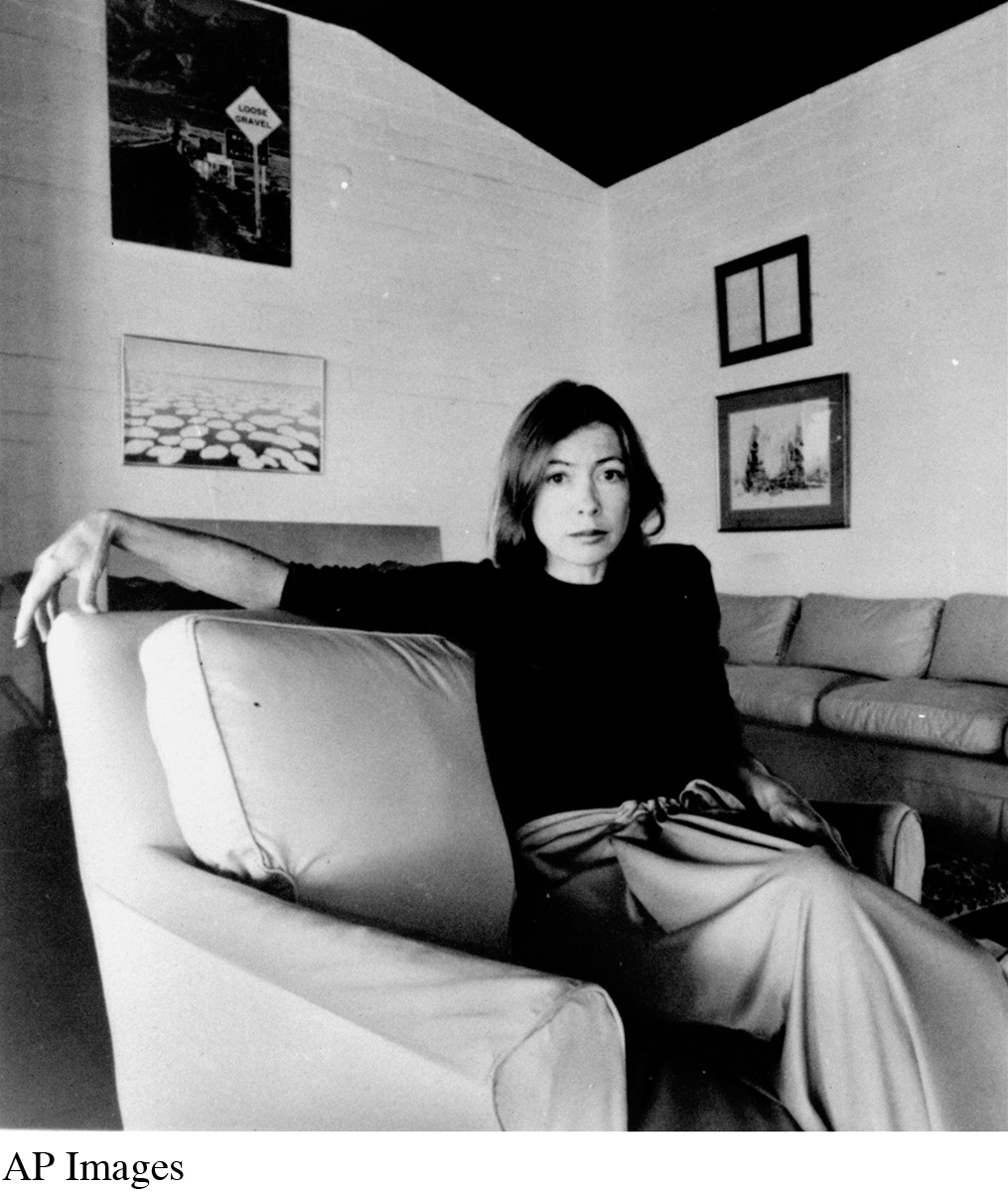

JOAN DIDION’S two essay collections—

Throughout the first part of the twentieth century—

In the 1960s, Tom Wolfe, a leading practitioner of new journalism, argued for mixing the content of reporting with the form of fiction to create “both the kind of objective reality of journalism” and “the subjective reality” of the novel.17 Writers such as Wolfe (The Electric Kool-

The Attack on Journalistic Objectivity

Former New York Times columnist Tom Wicker argued that in the early 1960s an objective approach to news remained the dominant model. According to Wicker, the “press had so wrapped itself in the paper chains of ‘objective journalism’ that it had little ability to report anything beyond the bare and undeniable facts.”18 Through the 1960s, attacks on the detachment of reporters escalated. News critic Jack Newfield rejected the possibility of genuine journalistic impartiality and argued that many reporters had become too trusting and uncritical of the powerful: “Objectivity is believing people with power and printing their press releases.”19 Eventually, the ideal of objectivity became suspect along with the authority of experts and professionals in various fields.

A number of reporters responded to the criticism by rethinking the framework of conventional journalism and adopting a variety of alternative techniques. One of these was advocacy journalism, in which the reporter actively promotes a particular cause or viewpoint. Precision journalism, another technique, attempts to make the news more scientifically accurate by using poll surveys and questionnaires. Throughout the 1990s, precision journalism became increasingly important. However, critics have charged that in every modern presidential campaign—

| Journalist(s) | Title or Subject | Publisher | Year(s) |

| 1 John Hersey | “Hiroshima” | New Yorker | 1946 |

| 2 Rachel Carson | Silent Spring | Houghton Mifflin | 1962 |

| 3 Bob Woodward/Carl Bernstein | Watergate investigation | Washington Post | 1972–73 |

| 4 Edward R. Murrow | Battle of Britain | CBS Radio | 1940 |

| 5 Ida Tarbell | “The History of the Standard Oil Company” | McClure’s Magazine | 1902–04 |

| 6 Lincoln Steffens | “The Shame of the Cities” | McClure’s Magazine | 1902–04 |

| 7 John Reed | Ten Days That Shook the World | Random House | 1919 |

| 8 H. L. Mencken | Coverage of the Scopes “monkey” trial | Baltimore Sun | 1925 |

| 9 Ernie Pyle | Reports from Europe and the Pacific during World War II | Scripps- |

1940–45 |

| 10 Edward R. Murrow/Fred Friendly | Investigation of Senator Joseph McCarthy | CBS Television | 1954 |

Table 8.2: TABLE 8.2 EXCEPTIONAL WORKS OF AMERICAN JOURNALISM Working under the aegis of New York University’s journalism department, thirty-

Contemporary Journalism in the TV and Internet Age

In the early 1980s, a postmodern brand of journalism arose from two important developments. In 1980, the Columbus Dispatch became the first paper to go online; today, nearly all U.S. papers offer some Web services. Then the colorful USA Today, started by Gannett, arrived in 1982, radically changing the look of most major U.S. dailies.

USA Today Colors the Print Landscape

USA Today made its mark by incorporating features closely associated with postmodern forms, including an emphasis on visual style over substantive news or analysis and the use of brief news items that appealed to readers’ busy schedules and shortened attention spans.

Now the second most widely circulated paper in the nation, USA Today represents the only successful launch of a new major U.S. daily newspaper in the last several decades. Showing its marketing savvy, USA Today was the first paper to openly acknowledge television’s central role in mass culture: The paper used TV-

Writing for Rolling Stone in March 1992, media critic Jon Katz argued that the authority of modern newspapers suffered in the wake of a variety of “new news” forms that combined immediacy, information, entertainment, persuasion, and analysis. Katz claimed that the news supremacy of most prominent daily papers, such as the New York Times and the Washington Post, was being challenged by “news” coming from talk shows, television sitcoms, popular films, and even rap music. In other words, society was changing from one in which the transmission of knowledge depended mainly on books, newspapers, and magazines to one dominated by a mix of print, visual, and digital information.

Online Journalism Redefines News

What started out in the 1980s as simple, text-

Another change is the way nontraditional sources and even newer digital technology help drive news stories. For example, the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement, inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings, began in September 2011 when a group of protesters gathered in Zuccotti Park in New York’s financial district to express discontentment with overpaid CEOs, big banks, and Wall Street, all of which helped cause the 2008–09 financial collapse but still enjoyed a government bailout.

Mainstream media was slow to cover OWS, with early coverage simply pitting angry protesters against dismissive Wall Street executives and politicians, many of whom questioned the movement’s longevity as well as its vague agenda. But as retirees, teachers, labor unions, off-

In the digital age, newsrooms are integrating their digital and print operations and asking their journalists to tweet breaking news that links back to newspapers’ Web sites. However, editors are still facing a challenge to get reporters and editors to fully embrace what news executives regard as a reporter’s online responsibilities. In 2011, for example, then executive editor of the New York Times Jill Abramson noted that although the Times had fully integrated its online and print operations, some editors still tried to hold back on publishing a timely story online, hoping that it would make the front page of the print paper instead. “That’s a culture I’d like to break down, without diminishing the [reporters’] thrill of having their story on the front page of the paper,” said Abramson.20 (For more about how online news ventures are changing the newspaper industry, see pages 298–301.)