Part Two Opener

PART 2

Sounds and Images

T he dominant media of the twentieth century were all about sounds and images: music, radio, television, and film. Each of these media industries was built around a handful of powerful groups—

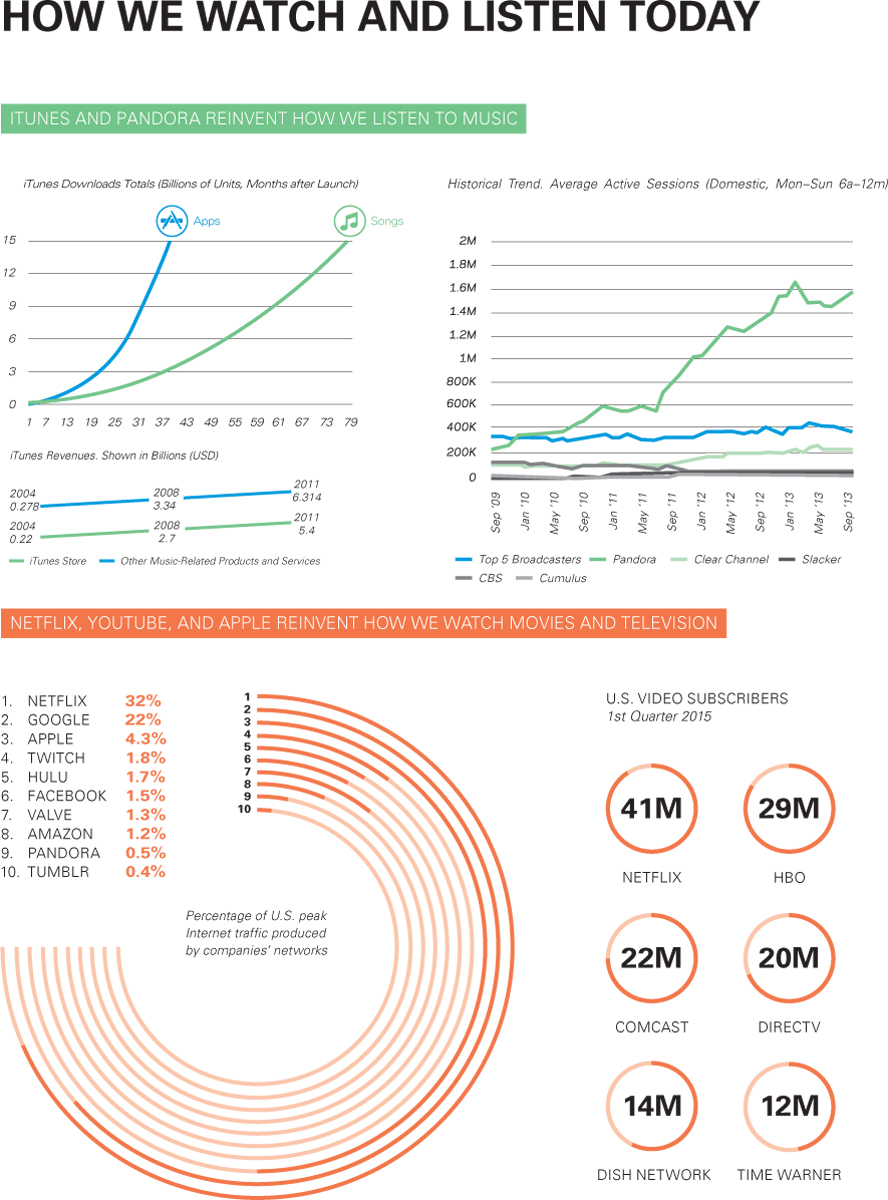

Music, radio, TV, and movies are still significant media in our lives. But convergence and the digital turn have changed the story of our sound and image media. Starting with the music industry and the introduction of Napster in 1999, one by one these media industries have had to cope with revolutionary changes. More than a decade later, the traditional media corporations have much less power in dictating what we listen to and watch. The narrative of ever-

We now live in a world where any and all media can be consumed via the Internet on laptops, tablets, smartphones, and video game consoles. As a result, we have seen the demise of record stores and video stores, local radio deejays, and the big network TV hit. Traditional media corporations are playing catch-

Moreover, as we consume all types of media content on a single device or through a single service, the traditionally separate “identities” of music, radio, television, and film have become blurred. For example, people might download an audio book and the latest pop single onto their iPods, or stream an album on a subscription service like Spotify, or listen to a genre of music on streaming radio. Similarly, more and more people are choosing to watch their video content on Netflix or Hulu—

The major media of the twentieth century are mostly still with us, but the twenty-