Part 1. LaunchPad for Media and Culture 12e Extended Case Study: Examining the Role of the Media in Election Coverage

Examining the Role of the Media in Election Coverage

Let’s get started! Click the forward and backward arrows to navigate through the slides. You may also click the above outline button to skip to certain slides.

The Iowa caucuses in February kicked off the first of the U.S. presidential election nominating contests in 2020. On the Republican side, the nomination of President Donald Trump wasn’t in doubt (especially after he was acquitted by the U.S. Senate the next day in his impeachment trial). On the Democratic side, at least eleven candidates—including Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and Andrew Yang—were still in contention to be Trump’s general election opponent in November.

On the evening of February 3, Iowa Democrats gathered in small neighborhood meetings in schools, churches, and meeting halls across the state, representing more than sixteen hundred precinct sites. But reporting those precinct vote tallies back to the state party headquarters via a new smartphone app didn’t go as planned.

The faulty app delayed the final results of the Democratic Party caucuses for that night by days. The news media seemed both perplexed and agitated, but not because Iowa wouldn’t eventually come up with an accurate count—in fact, for the first time at the Democratic caucus meetings, attendees used paper ballots to record their votes. Instead, the outrage of more than twenty-six hundred media members, including those from twenty-six countries, was due to their impatience in reporting the winners and losers, the story they had planned to tell. The lack of data that Monday evening left them without a way to tell that routine story.

CNN’s Chris Cuomo scolded the Iowa Democratic Party for not having prompt results and confirmed the news media’s role in what was supposed to happen in the political narrative: “[The campaigns] were making big bets on Iowa. Who was going to get talked about and in what way . . . especially with media and narratives. And that’s now been stalled. . . . And, literally, this state had one job . . . and they blew it at the most important time in the election.”1

Media That Reports—and Interprets—the News

Cuomo’s rant about the lack of immediate election results illustrates a key part of the relationship between the news media and U.S. elections. It’s hard to imagine an election in the United States in which we didn’t have the news media report and interpret the results for us. In the Democratic nominating contests after Iowa, for example, the results were more immediately clear, enabling the media to make quick projections of winners and losers, and equally quick conclusions about the meaning of the results. A look at headlines from the New York Times after the next four nominating contests shows how the paper framed the changing themes of the Democratic campaign story:

After Bernie Sanders won the New Hampshire primary, a Times analysis on the next day’s front page was titled “Establishment Finds Itself on the Outside.”

Following the Nevada caucus, which Sanders won even more convincingly, the front-page headline was “In Show of Might, Sanders Wins Nevada.”

In South Carolina, where Joe Biden had a big win (his first), the headline read “Vaulting to Life, Biden Captures South Carolina.”

After Super Tuesday, the March 3 contest with fourteen states, American Samoa, and Democrats abroad voting, the Times’ headline read “Big Night for Biden Serves Notice to Sanders.”2

These headlines suggest how we should interpret the outcomes of these contests and provide us with a story to follow into the general election.

Our Role as Citizens: The Importance of Media Literacy

While the media may present a narrative about election events, what is the role of everyday citizens in interacting with and interpreting the story or stories that media sources tell? Each individual plays an important role in thinking critically about this information and drawing conclusions from it.

Today’s political climate in the United States is perhaps at its most volatile in generations, and in the midst of an already chaotic primary season, the global pandemic of COVID-19 and its ensuing economic and social upheaval further disrupted the expected course of the 2020 presidential primaries and campaigns. The stability of our electoral system has been stressed like never before and the role of a free press in reporting on politics and elections is also in question, with an ascendant social media, rampant partisan propaganda, and information anarchy—from sources both foreign and domestic. After a 2016 presidential election in which U.S. investigators reached conclusive findings that the Russian government not only hacked computers and e-mail accounts of the Democratic National Committee and various Democratic presidential campaign workers and disclosed those stolen files but also operated a “social media campaign designed to provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States,”3 we need to be prepared as media-literate citizens to be ready for what 2020 and the following election years might throw at us.

In this Extended Case Study, we propose to use the critical process to investigate the potential problems we should anticipate in the 2020 election and its aftermath, and what we can do to be better informed and prepared to participate. As developed in Chapter 1, a media-literate perspective involves mastering five overlapping critical stages that build on one another, which collectively make up the critical process:

Description: paying close attention, taking notes, and researching the subject under study

Analysis: discovering and focusing on significant patterns that emerge from the description stage

Interpretation: asking and answering “What does that mean?” and “So what?” questions about one’s findings

Evaluation: arriving at a judgment about whether something is good, bad, or mediocre, which involves subordinating one’s personal taste to the critical “bigger picture” resulting from the first three stages

Engagement: taking some action that connects our critical perspective with our role as citizens and watchdogs to question our media institutions, adding our voice to the process of shaping the cultural environment.

We’ll explore each of these steps in more detail in the activity that follows.

But before we engage in the explicit steps of the critical process, let’s examine some of the potential problems and current threats to our elections and how the news media cover them. Any of these issues could be a path for you to investigate the intersection of the media and elections—institutions that are foundational to our democracy.

Value of reference one. Chris Cuomo, “Cuomo Scolds Iowa Democratic Party: You Had One Job,” CNN, February 4, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/videos/politics/2020/02/04/iowa-delay-results-caucuses-sot-vpx.cnn.

Value of reference one. See Matt Flegenheimer and Katie Glueck, “Establishment Finds Itself on the Outside,” New York Times, February 12, 2020, p. A1; Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, “In Show of Might, Sanders Wins Nevada,” New York Times, February 23, 2020, p. A1; Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, “Vaulting to Life, Biden Captures South Carolina,” New York Times, March 1, 2020, p. A1; Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, “Big Night for Biden Serves Notice to Sanders,” New York Times, March 4, 2020, p. A1.

Value of reference one. Robert S. Mueller, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, Office of the Special Counsel, March 2019, https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf, 4.

Problems of Traditional News Media Coverage

Horse-Race Coverage

Since the news media began conducting their own election polls in the 1970s, journalism has often reverted to “horse-race” coverage—who’s in the lead, who’s falling behind, and who’s gaining momentum.4 That’s the story that the news media was ready to tell on the night of the Iowa caucuses. Even CNN’s Chris Cuomo referred to the “big bets” candidates put on Iowa, making it sound like a wager at the Kentucky Derby. Terms like “dark horse” (a little-known horse that makes an unexpected first-place or high finish) also abound in election coverage. Try this: Google a candidate’s name and the term “dark horse.” Candidates like Buttigieg and Klobuchar got the title frequently, but candidates with higher poll numbers and media expectations—like Biden, Sanders, and Warren—were rarely identified that way.

The problem with horse-race coverage, according to the Encyclopedia of Political Communication, is that it “does little to inform and educate voters about domestic or foreign issues or policy issues that might directly affect the voters. Instead, such horse-race coverage tends to focus on the candidates and members of political parties as if they were celebrities, sports figures, or game show participants who are in a race or contest instead of a political campaign to hold public office and serve a constituency.”5

False Equivalence

In order to avoid seeming partisan, or in an effort to seem fair and balanced, the news media at times will resort to reporting things as equivalent when they are not. The classic example of our times is climate change. The consensus of 97 percent of scientists in thousands of research papers is that recent global warming is caused by humans.6 It would be absurd to suggest that this is a debate in which “both sides” are equal. In fact, the “other” side—which has sown distrust in scientific conclusions—is funded by the fossil fuel industries, which have great financial interest in doing so.7

The same false equivalence can occur in political and election coverage. For example, a study by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy found that in the news reports in the 2016 presidential campaign, “[Hillary] Clinton and [Donald] Trump’s coverage was virtually identical in terms of its negative tone.” The study’s lead author, Thomas E. Patterson, asked, “Were the allegations surrounding Clinton of the same order of magnitude as those surrounding Trump?” In this example, the news media treated Clinton’s use of the same computer server for her personal and official e-mails just as negatively as the recorded disclosure of Trump bragging about groping women without their consent, saying, “When you’re a star, they let you do it.” Patterson concluded that the news media were not cautious enough about the potential of false equivalence in their reporting. “It’s a question that political reporters made no serious effort to answer during the 2016 campaign.”8

The answer, of course, is not for the news media to give all sides of an issue equal time, space, and value—leaving the hard work of sorting through the information to citizens. Instead, journalists should evaluate and verify the information in their reports, thereby giving greater value to the news.

Value of reference one. Thomas Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980).

Value of reference one. Lynda Lee Kaid and Christina Holtz-Bacha, eds., Encyclopedia of Political Communication (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2008), 310.

Value of reference one. John Cook et al., “Consensus on Consensus: A Synthesis of Consensus Estimates on Human-Caused Global Warming,”Environmental Research Letters 11, no. 4 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

Value of reference one. Amy Westervelt, “How the Fossil Fuel Industry Got the Media to Think Climate Change Was Debatable,” Washington Post, January 10, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/01/10/how-fossil-fuel-industry-got-media-think-climate-change-was-debatable.

Value of reference one. Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, December 7, 2016, https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-general-election.

Problems of Partisan Media

The mainstream news media in the United States is generally moderate—more liberal or progressive in terms of certain social values and, because its owners are usually large media conglomerates, more conservative in regard to economic values. Separate in purpose from the mainstream media is the conservative partisan press, whose rise in the United States since the 1970s is well documented.9 Evangelical Christian cable television and radio was introduced in the 1970s, allying itself with the Republican Party. Then, conservative talk radio spread across America in the late 1980s with the success of radio host Rush Limbaugh, strengthening the alliance. In 1996, Fox News debuted, followed by a number of conservative websites, including the Daily Caller and Breitbart.

The problem is not that partisan media exist; the problem lies in suggesting that they are (in their editorial objectives) part of the mainstream news media. That would be a false equivalency. Fox News, for example, is the No. 1 rated cable news channel, but it is different in kind from CNN, MSNBC, and network television news organizations like ABC, CBS, NBC, as it is substantially and consistently allied with the Republican Party and President Trump. MSNBC may skew to the left of Fox and CNN (which is generally middle-of-the-road in its politics), but it would be inaccurate to describe it as the left-wing counterpart to Fox News. In fact, it tilts to the right with its morning news show, Morning Joe, cohosted by former Republican U.S. representative Joe Scarborough; and its Hardball host, Chris Matthews, was no friend of the left and was fired in March 2020, in part for demeaning characterizations of Elizabeth Warren’s and Bernie Sanders's campaigns. With hosts like Rachel Maddow and Chris Hayes, MSNBC may have a more progressive political perspective at times, but it does not align closely with a political party, as Fox News does.10 Understanding that conservative media outlets have a clear political agenda to elect conservative candidates and support conservative issues is essential to understanding and interpreting their news reports. Mainstream media outlets aren’t value-free either—being moderate is a political position as well—but they generally hew to journalism’s rules of truth-telling and verification.

Value of reference one. See Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Joseph N. Cappella, Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Christopher R. Martin, No Longer Newsworthy: How the Mainstream Media Abandoned the Working Class (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

Value of reference one. Christopher R. Martin, “Is There a Working-Class Cable News Channel?” Working-Class Perspectives, February 10, 2020, https://workingclassstudies.wordpress.com/2020/02/10/is-there-a-working-class-cable-news-channel. See also Michael M. Grynbaum, “Chris Matthews Out at MSNBC,” New York Times, March 7, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/02/business/media/chris-matthews-resigns-steps-down-msnbc.html; Jacob L. Nelson, “What Is Fox News? Researchers Want to Know,” Columbia Journalism Review, January 23, 2019, https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/fox-news-partisan-progaganda-research.php.

Problems of Social Media

Unlike traditional media, social media companies tend to shirk any editorial function. They view themselves as ultra-libertarian, with little or no responsibility for the messages carried on their platforms. The biggest of these social media sites are Google (and its subsidiary YouTube), Facebook (including its subsidiaries Instagram and WhatsApp), and Twitter. New York Times publisher A. G. Sulzberger noted that Google and Facebook have become “the most powerful distributors of news and information in human history, accidentally unleashing a historic flood of misinformation in the process.”11

We have already been alerted to the Russian government’s use of social media to foment social discord in the United States running up to the 2016 election (and continuing afterward). Other groups within and outside the United States have also used social media to disrupt elections. With so much disinformation, there has been increasing public pressure for social media companies to root it out, but they have generally been reluctant and slow to act.

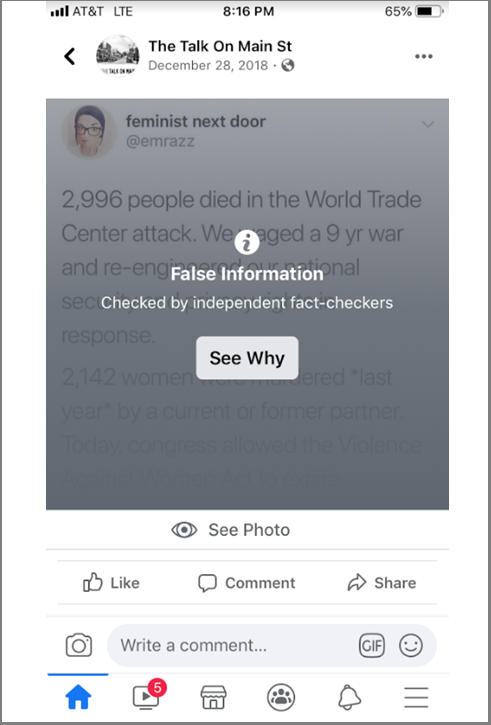

Twitter announced in 2019 that it would ban political advertising, in counterpoint to Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who defended continuing to accept political ads on that platform—even ones that contain disinformation.12 Hundreds of Facebook employees protested Zuckerberg’s decision, writing, “It doesn’t protect voices, but instead allows politicians to weaponize our platform by targeting people who believe that content posted by political figures is trustworthy.”13

Even in instances of social media messages that aren’t specifically presented as political advertising, posts by Internet trolls—people who post inflammatory or harassing messages and memes to elicit emotional reactions and sow discontent—abound, with the goal of subverting political campaigns and figures. In one example, presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren’s campaign asked for a doctored image posted by a troll to be taken down from Twitter. The image showed young women with signs at a Black Lives Matter protest, but the content on the signs had been altered to read “African Americans with Warren.” The image served to undermine credibility in Warren’s campaign, making it appear as though her own campaign created the phony image. Nevertheless, Twitter refused to take down the image, saying it did not violate its guidelines. While Twitter may refuse to accept political ads, misinformation posted by others can have the same negative effect.14

In another instance, both Twitter and Facebook refused Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s request to remove a video that made it look as if she were ripping up President Trump’s State of the Union speech while he was recognizing a Tuskegee airman and a military family. In fact, Pelosi ripped up Trump’s speech at the end of his address. Yet the deceptively altered video, which inserted video of her ripping paper to suggest she was being disrespectful to the airman and the military family, was posted by President Trump himself, on his own social media accounts, with the headline “Powerful American Stories Ripped to Shreds by Nancy Pelosi.”15

Facebook’s policy says it will remove “misleading manipulated media” if “it has been edited or synthesized—beyond adjustments for clarity or quality—in ways that aren’t apparent to an average person and would likely mislead someone into thinking that a subject of the video said words that they did not actually say.”16 However, Facebook concluded that Trump’s altered video of Pelosi didn’t meet this standard. In March 2020, Twitter began applying “manipulated media” labels on such misleading videos, yet that still falls short of removing them.17

Occasionally the source of a doctored video is revealed, comes under criticism, and voluntarily removes the post. For example, in 2016, during the Republican presidential primary campaign, an altered video posted on social media platforms made it appear as if Republican candidate Marco Rubio was criticizing the Bible. The source of the video was Rick Tyler, communications director of another Republican candidate, Ted Cruz. Cruz subsequently fired Tyler, the video posts were deleted, and Tyler posted an apology on Facebook.18 In this case, the content was removed by the party posting it, and social media platforms didn’t need to make a determination of whether the video fit their standards or not. But this kind of easy resolution to misinformation on social media is increasingly rare.

Value of reference one. A. G. Sulzberger, “The Growing Threat to Journalism around the World,” New York Times, September 23, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/23/opinion/press-freedom-arthur-sulzberger.html.

Value of reference one. Julia Carrie Wong, “Twitter to Ban All Political Advertising, Raising Pressure on Facebook,” Guardian, October 30, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/oct/30/twitter-ban-political-advertising-us-election.

Value of reference one. “Read the Letter Facebook Employees Sent to Mark Zuckerberg about Political Ads,” New York Times, October 28. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/28/technology/facebook-mark-zuckerberg-letter.html.

Value of reference one. Isaac Stanley-Becker and Tony Romm, “Opponents of Elizabeth Warren Spread a Doctored Photo on Twitter. Her Campaign Couldn’t Stop Its Spread.” Washington Post, November 27, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/11/27/opponents-elizabeth-warren-spread-doctored-photo-twitter-her-campaign-couldnt-stop-its-spread.

Value of reference one. Michael Levenson, “Pelosi Clashes with Facebook and Twitter over Video Posted by Trump,” New York Times, February 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/08/us/trump-pelosi-video-state-of-the-union.html.

Value of reference one. Monika Bickert, “Enforcing against Manipulated Media,” Facebook, January 6, 2020, https://about.fb.com/news/2020/01/enforcing-against-manipulated-media.

Value of reference one. Levenson, “Pelosi Clashes with Facebook and Twitter.”

Value of reference one. Ryan Lovelace and David M. Drucker, “Ted Cruz Fires Communications Director After Doctored Rubio Video,” Washington Examiner, February 22, 2016, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/ted-cruz-fires-communications-director-after-doctored-rubio-video.

Problems of Propaganda and Information Anarchists

Propaganda

Propagandists are official state actors who spread a coordinated partisan message meant to propagate a point of view. North Korea, Iraq, China, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Hungary, and Russia would be the most easily identifiable propagandists, with a secure hold on major media outlets and a sophisticated system of news and media that supports the goals of their regimes. The Russian government most infamously interfered with the 2016 election. As the Mueller report (the U.S. Justice Department document officially titled Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election) concluded, the Russian government used what it called an “information warfare” propaganda campaign, which “evolved from a generalized program designed in 2014 and 2015 to undermine the U.S. electoral system, to a targeted operation that by early 2016 favored candidate Trump and disparaged candidate Clinton.”19

Information Anarchy

Information anarchists are actors who want to stir the pot, make people angry with outrageous statements and allegations, and create doubt and mistrust (sometimes called “gaslighting”) in order to undermine the legitimacy of genuine news itself and create the perception that the truth might never be determined. Internet trolls are information anarchists, and they use various platforms, such as social media, to do their work.

Most information anarchists tend to remain anonymous, but some, like American radio host Alex Jones, built a communication empire with Infowars—his conspiracy theory website—and his radio show, The Alex Jones Show. Jones’s show often includes shocking allegations. He falsely claimed, for example, that the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings in Newtown, Connecticut, were a government operation meant to increase support for gun control. In 2018, a number of platforms, including Apple, Spotify, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and PayPal, removed Jones’s Infowars app from their sites for violating their policies, including those on hate speech.

The unprecedented record of false and misleading claims made by President Trump can also be categorized as information anarchy. The Washington Post counted 16,241 of these claims by January 20, 2020, three full years into his presidency, with a rate of more than twenty-two false or misleading claims per day by 2019. These included claims that the U.S. economy is the best in history (economic growth was actually better under Presidents Reagan and Clinton), that the border wall is being built (some replacement fencing was going up, not the 1,000-mile concrete barrier promised in 2016), and that he passed the largest tax cut in history (when it was only the eighth largest since the 1980s).20 President Trump has also used information anarchy to cast doubt on other verifiable facts, such as his longtime “birther” campaign that questioned President Obama’s U.S. citizenship, and his persistent labeling of mainstream news organizations and some of their reports as “fake news.” Trump’s approach is to use sheer repetition of his claims to promote his narrative of the events occurring across the nation and in his administration.

Value of reference one. Mueller, Report on the Investigation, 4.

Value of reference one. See Glenn Kessler, Salvador Rizzo, and Meg Kelly, “President Trump Made 16,241 False or Misleading Claims in His First Three Years,” Washington Post, February 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/01/20/president-trump-made-16241-false-or-misleading-claims-his-first-three-years/; Heather Long, “Trump Touts His Economy as ‘the Best It Has Ever Been.’ The Data Doesn’t Show That,” Washington Post, February 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/02/04/trump-touts-his-economy-best-ever-data-is-more-mixed; Elyse Samuels, “Fact-Checking Trump’s Misleading Border ‘Wall’ Spin,” Washington Post, October 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/10/11/fact-checking-trumps-misleading-border-wall-spin; Glenn Kessler, “Fact Check: Biggest Tax Cut in U.S. History?” Washington Post, January 30, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2018/live-updates/trump-white-house/fact-checking-and-analysis-of-trumps-state-of-the-union-2018-address/fact-check-biggest-tax-cut-in-u-s-history.

Becoming a Media-Literate Citizen

When you encounter election-related media issues like those we’ve just examined, you can work through the critical process to develop a better understanding of how the media, politics, and elections intersect. For the purposes of this activity, we’ll use the critical process to investigate one particular issue—horse-race coverage in the news—and consider the implication of how that coverage is presented in various media sources.

Description

In the description stage of the critical process, you research the subject under study. Sample a few days or a week of reports from several national news organizations, finding five to ten horse-race news stories about the presidential election. The stories can be in newspapers (such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, or the Los Angeles Times), on cable television or network news (such as CNN, MSNBC, ABC, CBS, or NBC), or radio (such as NPR). Note the elements that make these stories count as horse-race news stories, such as mention of polls or surveys, strategies the candidates can use to win, and projections for the campaigns to win key states in the Electoral College.

Analysis

In the analysis stage of the critical process, you focus on significant patterns that emerge from the description stage. What are the patterns that emerge in the reports you just examined? What seem to be the common elements of horse-race news stories? What kinds of things are missing from political news stories that have a horse-race focus?

Interpretation

In the interpretation stage of the critical process, you try to determine the meanings of the patterns you analyzed. What does it mean when the news carries horse-race campaign stories? Are these stories easier to report than other types of stories? Are they more dramatic or interesting than other types of political news stories? Remember, the problem with overemphasis on horse-race coverage is that policy issues are neglected, and the narrative sounds more like a popularity contest than a process to determine the best leader for public office. Do you detect these same problems in your analysis and interpretation?

Evaluation

In the evaluation stage of the critical process, you make an informed judgment about whether something is good, bad, or mediocre based on the critical assessment resulting from the first three stages. What do you think of the national news coverage of the presidential campaign you sampled—good, bad, or lacking in some ways but better in others? Should the news media avoid horse-race coverage completely, limit it, or keep the emphasis as it is? Should stories on who is leading or behind (and any related surveys) be suspended for a certain period before Election Day to avoid influencing how people vote—or whether they vote at all?

Engagement

In the engagement stage of the critical process, you take some action that connects your critical interpretations and evaluations with your responsibility as a citizen. What kind of information will you look for before you vote? What will you avoid? What sources will you recommend to your family and friends? And (most importantly), will you vote? Americans need better information literacy, but then they also need to actually vote. Between 52 and 62 percent of the country’s voting-age citizens voted in each presidential election in the past fifty years. That is relatively dismal, compared to 87 percent of the voting age population in Belgium, 83 percent in Sweden, 80 percent in Denmark, 79 percent in Australia, 78 percent in South Korea, 69 percent in Germany, and 68 percent in France.21 About 42 percent of eligible voters did not vote in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Something to consider: Do you think the quality (or lack of quality) in news media stories is part of the problem getting people to vote?

Value of reference one. Drew DeSilver, “U.S. Trails Most Developed Countries in Voter Turnout,” Pew Research Center, May 21, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most-developed-countries.