Problems of Social Media

Unlike traditional media, social media companies tend to shirk any editorial function. They view themselves as ultra-libertarian, with little or no responsibility for the messages carried on their platforms. The biggest of these social media sites are Google (and its subsidiary YouTube), Facebook (including its subsidiaries Instagram and WhatsApp), and Twitter. New York Times publisher A. G. Sulzberger noted that Google and Facebook have become “the most powerful distributors of news and information in human history, accidentally unleashing a historic flood of misinformation in the process.”11

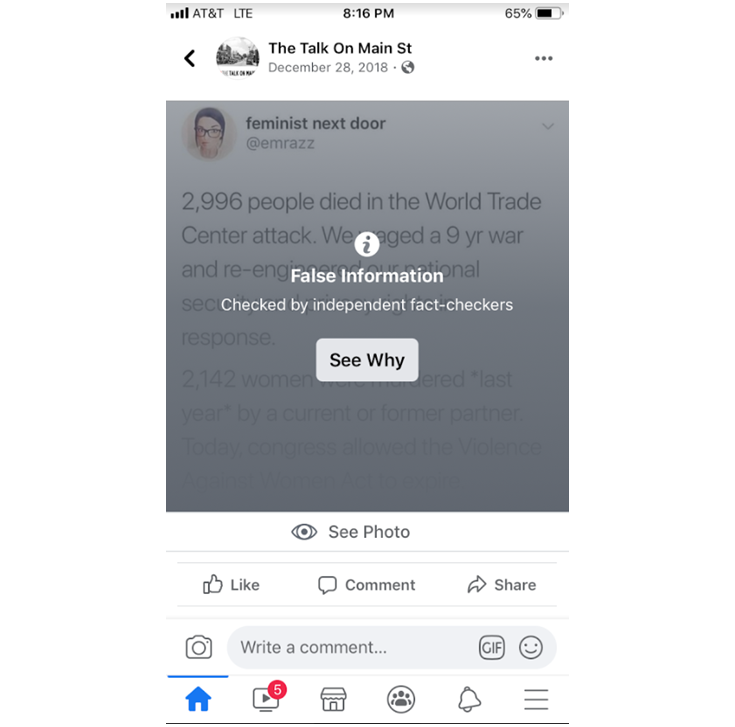

We have already been alerted to the Russian government’s use of social media to foment social discord in the United States running up to the 2016 election (and continuing afterward). Other groups within and outside the United States have also used social media to disrupt elections. With so much disinformation, there has been increasing public pressure for social media companies to root it out, but they have generally been reluctant and slow to act.

Twitter announced in 2019 that it would ban political advertising, in counterpoint to Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who defended continuing to accept political ads on that platform—even ones that contain disinformation.12 Hundreds of Facebook employees protested Zuckerberg’s decision, writing, “It doesn’t protect voices, but instead allows politicians to weaponize our platform by targeting people who believe that content posted by political figures is trustworthy.”13

Even in instances of social media messages that aren’t specifically presented as political advertising, posts by Internet trolls—people who post inflammatory or harassing messages and memes to elicit emotional reactions and sow discontent—abound, with the goal of subverting political campaigns and figures. In one example, presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren’s campaign asked for a doctored image posted by a troll to be taken down from Twitter. The image showed young women with signs at a Black Lives Matter protest, but the content on the signs had been altered to read “African Americans with Warren.” The image served to undermine credibility in Warren’s campaign, making it appear as though her own campaign created the phony image. Nevertheless, Twitter refused to take down the image, saying it did not violate its guidelines. While Twitter may refuse to accept political ads, misinformation posted by others can have the same negative effect.14

In another instance, both Twitter and Facebook refused Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s request to remove a video that made it look as if she were ripping up President Trump’s State of the Union speech while he was recognizing a Tuskegee airman and a military family. In fact, Pelosi ripped up Trump’s speech at the end of his address. Yet the deceptively altered video, which inserted video of her ripping paper to suggest she was being disrespectful to the airman and the military family, was posted by President Trump himself, on his own social media accounts, with the headline “Powerful American Stories Ripped to Shreds by Nancy Pelosi.”15

Facebook’s policy says it will remove “misleading manipulated media” if “it has been edited or synthesized—beyond adjustments for clarity or quality—in ways that aren’t apparent to an average person and would likely mislead someone into thinking that a subject of the video said words that they did not actually say.”16 However, Facebook concluded that Trump’s altered video of Pelosi didn’t meet this standard. In March 2020, Twitter began applying “manipulated media” labels on such misleading videos, yet that still falls short of removing them.17

Occasionally the source of a doctored video is revealed, comes under criticism, and voluntarily removes the post. For example, in 2016, during the Republican presidential primary campaign, an altered video posted on social media platforms made it appear as if Republican candidate Marco Rubio was criticizing the Bible. The source of the video was Rick Tyler, communications director of another Republican candidate, Ted Cruz. Cruz subsequently fired Tyler, the video posts were deleted, and Tyler posted an apology on Facebook.18In this case, the content was removed by the party posting it, and social media platforms didn’t need to make a determination of whether the video fit their standards or not. But this kind of easy resolution to misinformation on social media is increasingly rare.

11A. G. Sulzberger, “The Growing Threat to Journalism around the World,” New York Times, September 23, 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/09/23/opinion/press-freedom-arthur-sulzberger.html.

12Julia Carrie Wong, “Twitter to Ban All Political Advertising, Raising Pressure on Facebook,” Guardian, October 30, 2019, www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/oct/30/twitter-ban-political-advertising-us-election.

13“Read the Letter Facebook Employees Sent to Mark Zuckerberg about Political Ads,” New York Times, October 28. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/10/28/technology/facebook-mark-zuckerberg-letter.html.

14Isaac Stanley-Becker and Tony Romm, “Opponents of Elizabeth Warren Spread a Doctored Photo on Twitter. Her Campaign Couldn’t Stop Its Spread.” Washington Post, November 27, 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/11/27/opponents-elizabeth-warren-spread-doctored-photo-twitter-her-campaign-couldnt-stop-its-spread.

15Michael Levenson, “Pelosi Clashes with Facebook and Twitter over Video Posted by Trump,” New York Times, February 8, 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/02/08/us/trump-pelosi-video-state-of-the-union.html.

16Monika Bickert, “Enforcing against Manipulated Media,” Facebook, January 6, 2020, https://about.fb.com/news/2020/01/enforcing-against-manipulated-media.

17Levenson, “Pelosi Clashes with Facebook and Twitter.”

18Ryan Lovelace and David M. Drucker, “Ted Cruz Fires Communications Director After Doctored Rubio Video,” Washington Examiner, February 22, 2016, www.washingtonexaminer.com/ted-cruz-fires-communications-director-after-doctored-rubio-video.