Case Study

CASE STUDY

Comic Books: Alternative Themes, but Superheroes Prevail

by Mark C. Rogers

At the precarious edge of the book industry are comic books, which are sometimes called graphic novels or simply comix. Comics have long integrated print and visual culture, and they are perhaps the medium most open to independent producers—anyone with a pencil and access to a photocopier can produce mini-comics. Nevertheless, two companies—Marvel and DC—have dominated the commercial industry for more than thirty years, publishing the routine superhero stories that have been so marketable.

Comics are relatively young, first appearing in their present format in the 1920s in Japan and in the 1930s in the United States. They began as simple reprints of newspaper comic strips, but by the mid-1930s most comic books featured original material. Comics have always been published in a variety of genres, but their signature contribution to American culture has been the superhero. In 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman for DC comics. Bob Kane’s Batman character arrived the following year. In 1941, Marvel Comics introduced Captain America to fight Nazis, and except for a brief period in the 1950s, the superhero genre has dominated the history of comics.

After World War II, comic books moved away from superheroes and began experimenting with other genres, most notably crime and horror (e.g., Tales from the Crypt). With the end of the war, the reading public was ready for more moral ambiguity than was possible in the simple good-versus-evil world of the superhero. Comics became increasingly graphic and lurid as they tried to compete with other mass media, especially television and mass market paperbacks.

In the early 1950s, the popularity of crime and horror comics led to a moral panic about their effects on society. Frederic Wertham, a prominent psychiatrist, campaigned against them, claiming they led to juvenile delinquency. Wertham was joined by many religious and parent groups, and Senate hearings were held on the issue. In October 1954, the Comics Magazine Association of America adopted a code of acceptable conduct for publishers of comic books. One of the most restrictive examples of industry self-censorship in mass-media history, the code kept the government from legislating its own code or restricting the sale of comic books to minors.

The code had both immediate and long±term effects on comics. In the short run, the number of comics sold in the United States declined sharply. Comic books lost many of their adult readers because the code confined comics’ topics to those suitable for children. Consequently, comics have rarely been taken seriously as a mass medium or as an art form; they remain stigmatized as the lowest of low culture—a sort of literature for the subliterate.

In the 1960s, Marvel and DC led the way as superhero comics regained their dominance. This period also gave rise to underground comics, which featured more explicit sexual, violent, and drug themes—for example, R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural and Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead. These alternative comics, like underground newspapers, originated in the 1960s counterculture and challenged the major institutions of the time. Instead of relying on newsstand sales, underground comics were sold through record stores, at alternative bookstores, and in a growing number of comic-book specialty shops.

In the 1970s, responding in part to the challenge of the underground form, “legitimate” comics began to increase the political content and relevance of their story lines. In 1974, a new method of distributing comics—direct sales—developed, catering to the increasing number of comic-book stores. This direct-sales method involved selling comics on a nonreturnable basis but with a higher discount than was available to newsstand distributors, who bought comics only on the condition that they could return unsold copies. The percentage of comics sold through specialty shops increased gradually, and by the early 1990s more than 80 percent of all comics were sold through direct sales.

The shift from newsstand to direct sales enabled comics to once again approach adult themes and also created an explosion in the number of comics available and in the number of companies publishing comics. Comic books peaked in 1993, generating more than $850 million in sales. That year the industry sold about 45 million comic books per month, but it then began a steady decline that led Marvel to declare bankruptcy in the late 1990s. After comic-book sales fell to $250 million in 2000 and Marvel reorganized, the industry rebounded. Today, the industry releases 70 to 80 million comics a year. Marvel and DC control more than 70 percent of comic-book sales, but challengers like Image, Dark Horse, and IDW plus another 150 small firms keep the industry vital by providing innovation and identifying new talent.

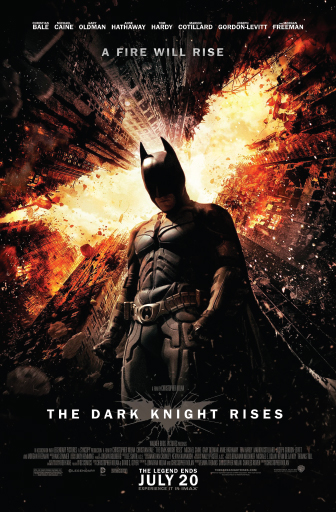

Meanwhile, the two largest firms focus on the commercial synergies of particular characters or superheroes. DC, for example, is owned by Time Warner, which has used the DC characters, especially Superman and Batman, to build successful film and television properties through its Warner Brothers division. Marvel, which was bought by Disney in 2009, also got into the licensing act with film versions of Spider-Man and The Avengers.

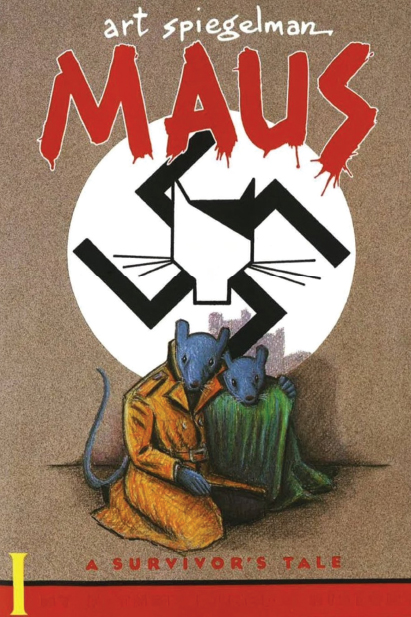

Comics, however, are again about more than just superheroes. In 1992, comics’ flexibility was demonstrated in Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman, cofounder and editor of Raw (an alternative magazine for comics and graphic art). The first comic-style book to win a Pulitzer Prize, Spiegelman’s two-book fable merged print and visual styles to recount his complex relationship with his father, a Holocaust survivor.

Today, there are few divisions among traditional books and graphic novels. In 2012–13, Seven Stories Press released a three-volume book, The Graphic Canon: The World’s Great Literature as Comics and Visuals. The acclaimed collection uses 130 illustrators to reinterpret nearly 190 classic texts, from the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh, to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, to twentieth-century works like Wild at Heart by Barry Gifford.

As other writers and artists continue to adapt the form to both fictional and nonfictional stories, comics endure as part of popular and alternative culture.

Mark C. Rogers teaches communication at Walsh University. He writes about television and the comic-book industry.