The Structure of Book Publishing

A small publishing house may have a staff of a few to twenty people. Medium-size and large publishing houses employ hundreds of people. In the larger houses, divisions usually include acquisitions and development; copyediting, design, and production; marketing and sales; and administration and business. Unlike daily newspapers but similar to magazines, most publishing houses contract independent printers to produce their books.

Most publishers employ acquisitions editors to seek out and sign authors to contracts. For fiction, this might mean discovering talented writers through book agents or reading unsolicited manuscripts. For nonfiction, editors might examine manuscripts and letters of inquiry or match a known writer to a project (such as a celebrity biography). Acquisitions editors also handle subsidiary rights for an author—that is, selling the rights to a book for use in other media, such as a mass market paperback or as the basis for a screenplay.

As part of their contracts, writers sometimes receive advance money, an early payment that is subtracted from royalties earned from book sales (see Figure 10.4). Typically, an author’s royalty is between 5 and 15 percent of the net price of the book. New authors may receive little or no advance from a publisher, but commercially successful authors can receive millions. For example, Interview with a Vampire author Anne Rice hauled in a $17 million advance from Knopf for three more vampire novels. Nationally recognized authors, such as political leaders, sports figures, or movie stars, can also command large advances from publishers who are banking on the well-known person’s commercial potential. For example, Sarah Palin received $1.25 million for her book, Going Rogue, and George W. Bush got a $7 million advance for Decision Points, both released in 2010.

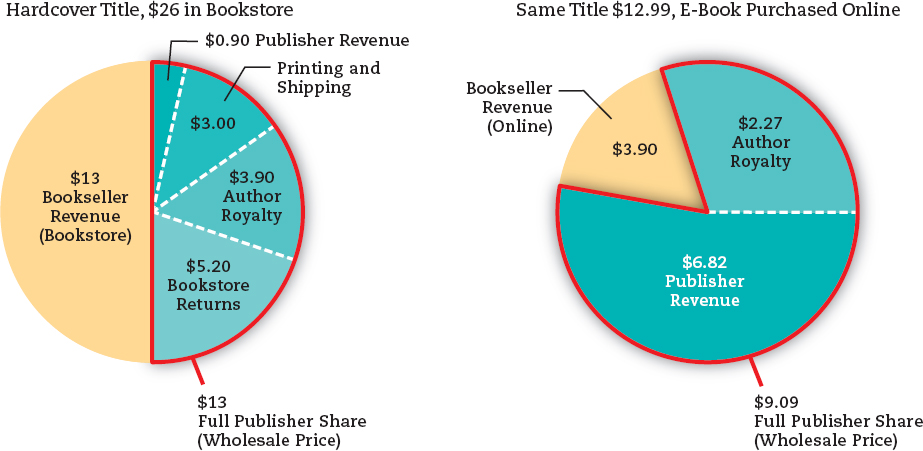

Booksellers are still dependent on printed books, but e-books are changing the nature of business expenses, profits, and costs to consumers. Here’s where the money goes on a $26 trade book and the same title sold as a $12.99 e-book.

Source: Ken Auletta, “Publish or Perish: Can the iPad Topple the Kindle, and Save the Book Business?” New Yorker, April 26, 2010, 24±31.

Note: Publishers and booksellers must pay other expenses, such as employees and office/retail space, from their revenue share.

After a contract is signed, the acquisitions editor may turn the book over to a developmental editor who provides the author with feedback, makes suggestions for improvements, and, in educational publishing, obtains advice from knowledgeable members of the academic community. If a book is illustrated, editors work with photo researchers to select photographs and pieces of art. Then the production staff enters the picture. While copy editors attend to specific problems in writing or length, production and design managers work on the look of the book, making decisions about type style, paper, cover design, and layout.

Simultaneously, plans are under way to market and sell the book. Decisions need to be made concerning the number of copies to print, how to reach potential readers, and costs for promotion and advertising. For trade books and some scholarly books, publishing houses may send advance copies of a book to appropriate magazines and newspapers with the hope of receiving favorable reviews that can be used in promotional material. Prominent trade writers typically have book signings and travel the radio and TV talk-show circuit to promote their books. Unlike trade publishers, college textbook firms rarely sell directly to bookstores. Instead, they contact instructors through direct-mail brochures or sales representatives assigned to geographic regions.

To help create a best-seller, trade houses often distribute large illustrated cardboard bins, called dumps, to thousands of stores to display a book in bulk quantity. Like food merchants who buy eye-level shelf placement for their products in supermarkets, large trade houses buy shelf space from major chains to ensure prominent locations in bookstores. For example, to have copies of one title placed in a front-of-the-store dump bin or table at all Barnes & Noble bookstore locations costs $10,000–$20,000 for just a few weeks.13 Publishers also buy ad space in newspapers and magazines and on buses, billboards, television, radio, and the Web—all in an effort to generate interest in a new book.