Selling Books: Brick-and-Mortar Stores, Clubs, and Mail Order

“[Barnes & Noble has] an important friend: The publishers, who hate the idea of an all-Amazon world.”

LYDIA DEPILLIS, WASHINGTON POST, 2013

Traditionally, the final part of the publishing process involves the business and order fulfillment stages—shipping books to thousands of commercial outlets and college bookstores. Warehouse inventories are monitored to ensure that enough copies of a book will be available to meet demand. Anticipating such demand, though, is a tricky business. No publisher wants to be caught short if a book becomes more popular than originally predicted or get stuck with books it cannot sell, as publishers must absorb the cost of returned books. Independent bookstores, which tend to order more carefully, return about 20 percent of books ordered; in contrast, mass merchandisers such as Walmart, Sam’s Club, Target, and Costco, which routinely overstock popular titles, often return up to 40 percent. Returns this high can seriously impact a publisher’s bottom line. For years, publishers have talked about doing away with the practice of allowing bookstores to return unsold books to the publisher for credit.

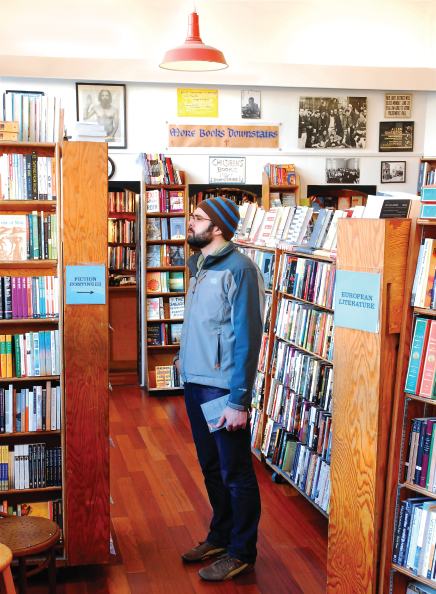

INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORES City Lights Books in San Francisco, CA, is both an independent bookstore and an independent publisher, publishing nearly 200 titles since launching in 1955, including poet Allen Ginsberg’s revolutionary work Howl. Customers from around the world now come to browse through the landmark store’s three floors and to see the place where “beatniks” like Ginsberg got their start.

Today, about 15,000 outlets sell books in the United States, including traditional bookstores, department stores, drugstores, used-book stores, and toy stores. Shopping-mall bookstores boosted book sales starting in the late 1960s. But it was the development of book superstores in the 1980s that really reinvigorated the business. Following the success of a single Borders store in Ann Arbor, Michigan, a number of book chains began developing book superstores that catered to suburban areas and to avid readers. A typical Barnes & Noble superstore stocks up to 200,000 titles. As superstores expanded, they began to sell recorded music and feature coffee shops and live performances. Borders grew from 14 superstores in 1991 to more than 508 superstores and 173 Waldenbooks by 2010, but the company declared bankruptcy and closed its last brick-and-mortar store in 2011. Since the shuttering of Borders, Barnes & Noble is the last national bookstore retail chain in the United States, operating 675 superstores and 686 college bookstores, but closing its smaller B. Dalton mall bookstores in 2010.

The rise of book superstores (and later, online bookstores) severely cut into independent bookstore business, which dropped from a 31 percent market share in 1991 to 4.3 percent by 2011.14 The number of independent bookstores dropped from 5,100 in 1991 to about 1,900 today. Independent bookstores and superstore chains are being squeezed from multiple sides: online and e-book sales; big discount retailers such as Walmart, Sam’s Club, Target, and Costco; and specialty retailers like Anthropologie and Urban Outfitters that sell “lifestyle” books.15

Book clubs and mail-order services are two other traditional methods of selling books. Originally, these two tactics helped the industry when local bookstores were rarer and long before the Internet existed.

The Book-of-the-Month Club and the Literary Guild both started in 1926. Using popular writers and literary experts to recommend new books, the clubs were immediately successful. Book clubs have long served as editors for their customers, screening thousands of titles and recommending key books in particular genres. During the 1980s, book clubs began a long decline in sales. Today, twenty remaining book clubs—including the Book-of-the-Month Club, the Literary Guild, and Doubleday—are consolidated by a single company, Pride Tree Holdings, which also owns DVD and music clubs.

“Amazon is not in most of the headlines, but all of the big events in the book world are about Amazon.”

PAUL AIKEN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE AUTHORS GUILD , NEW YORK TIMES, 2013

Mail-order bookselling was pioneered in the 1950s by magazine publishers. They created special sets of books, including Time-Life Books, focusing on such areas as science, nature, household maintenance, and cooking. These series usually offered one book at a time and sustained sales through direct-mail flyers and other advertising. Although such sets are more costly due to advertising and postal charges, mail-order books still appeal to customers who prefer mail to the hassle of shopping or to those who prefer the privacy of mail order (particularly if they are ordering sexually explicit books or magazines). Today mail-order bookselling is used primarily by trade, professional, and university press publishers.