Types of Books

“He was a genius at devising ways to put books into the hands of the unbookish.”

EDNA FERBER, WRITER, COMMENTING ON NELSON DOUBLEDAY, PUBLISHER

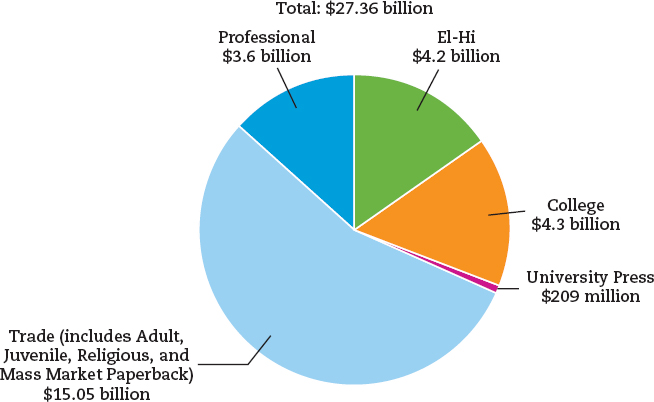

The divisions of the modern book industry come from economic and structural categories developed both by publishers and by trade organizations such as the Association of American Publishers (AAP), the Book Industry Study Group (BISG), and the American Booksellers Association (ABA). The categories of book publishing that exist today include trade books (both adult and juvenile), professional books, elementary through high school (often called “el-hi”) and college textbooks, mass market paperbacks, religious books, reference books, and university press books. (For sales figures for the book types, see Figure 10.1.)

Trade Books

One of the most lucrative parts of the industry, trade books include hardbound and paperback books aimed at general readers and sold at commercial retail outlets. The industry distinguishes among adult trade, juvenile trade, and comics and graphic novels. Adult trade books include hardbound and paperback fiction; current nonfiction and biographies; literary classics; books on hobbies, art, and travel; popular science, technology, and computer publications; self-help books; and cookbooks. (Betty Crocker’s Cookbook, first published in 1950, has sold more than twenty-two million hardcover copies.)

Source: Ned May, “Making Information Pay 2013: A First Look at BookStats,” May 15, 2013, www.slideshare.net/bisg/mip-2013-bookstats-first-look-ned-may.

Juvenile book categories range from preschool picture books to young-adult or young-reader books, such as Dr. Seuss books, the Lemony Snicket series, the Fear Street series, and the Harry Potter series. In fact, the Harry Potter series alone provided an enormous boost to the industry, helping create record-breaking first-press runs: 10.8 million for Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2005) and 12 million for the final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007).

Since 2003, the book industry has also been tracking sales of comics and graphic novels (long-form stories with frame-by-frame drawings and dialogue, bound like books). As with the similar Japanese manga books, graphic novels appeal to both youth and adult, as well as male and female, readers. Will Eisner’s A Contract with God (1978) is generally credited as the first graphic novel (and called itself so on its cover). Since that time interest in graphic novels has grown, and in 2006 their sales surpassed comic books. Given their strong stories and visual nature, many movies have been inspired by comics and graphic novels, including X-Men, The Dark Knight, Watchmen, and Captain America. But graphic novels aren’t only about warriors and superheroes. Maira Kalman’s Principles of Uncertainty and Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? are both acclaimed graphic novels, but their characters are regular mortals in real settings. (See “Case Study—Comic Books: Alternative Themes, but Superheroes Prevail” on pages 356-357.)

Professional Books

“The great thing about novels, and the reason we still need them—I think we’ll always need them—is you’re converting unsayable things into narratives with their own dreamlike reality.”

JONATHAN FRANZEN, NPR: FRESH AIR, SEPTEMBER 2010

The counterpart to professional trade magazines, professional books target various occupational groups and are not intended for the general consumer market. This area of publishing capitalizes on the growth of professional specialization that has characterized the job market, particularly since the 1960s. Traditionally, the industry has subdivided professional books into the areas of law, business, medicine, and technical-scientific works, with books in other professional areas accounting for a very small segment. These books are sold through mail order, the Internet, or sales representatives knowledgeable about the subject areas.

Textbooks

The most widely read secular book in U.S. history was The Eclectic Reader, an elementary-level reading textbook first written by William Holmes McGuffey, a Presbyterian minister and college professor. From 1836 to 1920, more than 100 million copies of this text were sold. Through stories, poems, and illustrations, The Eclectic Reader taught nineteenth-century schoolchildren to spell and read simultaneously—and to respect the nation’s political and economic systems. Ever since the publication of the McGuffey reader (as it is often nicknamed), textbooks have served a nation intent on improving literacy rates and public education. Elementary school textbooks found a solid market niche in the nineteenth century, while college textbooks boomed in the 1950s when the GI Bill enabled hundreds of thousands of working- and middle-class men returning from World War II to attend college. The demand for textbooks further accelerated in the 1960s as opportunities for women and minorities expanded. Textbooks are divided into elementary through high school (el-hi) texts, college texts, and vocational texts.

“California has the ability to say, ‘We want textbooks this way.’”

TOM ADAMS, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2004

In about half of the states, local school districts determine which el-hi textbooks are appropriate for their students. The other half of the states, including Texas and California, the two largest states, have statewide adoption policies that decide which texts can be used. If individual schools choose to use books other than those mandated, they are not reimbursed by the state for their purchases. Many teachers and publishers have argued that such sweeping authority undermines the autonomy of individual schools and local school districts, which have varied educational needs and problems. In addition, many have complained that the statewide system in Texas and California enables these two states to determine the content of all el-hi textbooks sold in the nation because publishers are forced to appeal to the content demands of these states. However, the two states do not always agree on what should be covered. In 2010, the Texas State Board of Education adopted more conservative interpretations of social history in its curriculum, while the California State Board of Education called for more coverage of minorities’ contributions in U.S. history. The disagreement pulled textbook publishers in opposite directions. The solution, which is becoming increasingly easier to implement, involves customizing electronic textbooks according to state standards.

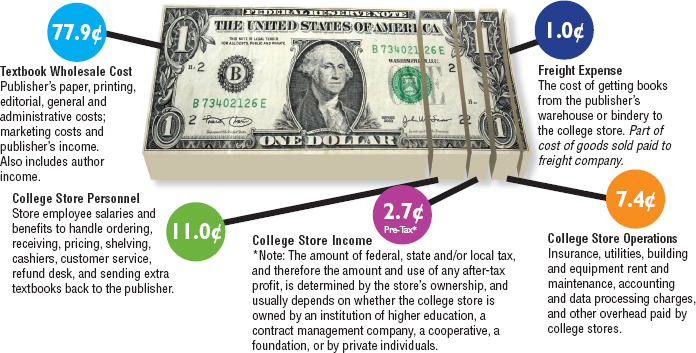

Unlike el-hi texts, which are subsidized by various states and school districts, college texts are paid for by individual students (and parents) and are sold primarily through college bookstores. The increasing cost of textbooks, the markup on used books, and the profit margins of local college bookstores (which in many cases face no on-campus competition) have caused disputes on most college campuses. A 2011–12 survey indicated that each college student spent an annual average of $420 on required course texts, including $296 on new and $124 on used textbooks.7 (See Figure 10.2.)

Source: © 2013 by the National Association of College Stores, www.nacs.org/research/industrystatistics.aspx.

*College store numbers are averages and reflect the most current data gathered by the National Association of College Stores.

As an alternative, some enterprising students have developed Web sites to trade, resell, and rent textbooks. Other students have turned to online purchasing, either through e-commerce sites like Amazon.com, BarnesandNoble.com, and eBay.com, or through college textbook sellers like eCampus.com and textbooks.com, or through book renters like Chegg.com.

Mass Market Paperbacks

Unlike the larger-size trade paperbacks, which are sold mostly in bookstores, mass market paperbacks are sold on racks in drugstores, supermarkets, and airports as well as in bookstores. Contemporary mass market paperbacks are often the work of blockbuster authors such as Stephen King, Nora Roberts, Patricia Cornwell, and John Grisham and are typically released in the low-cost (under $10) format months after publication of the hardcover version. But, mass market paperbacks have experienced declining sales in recent years and now account for less than 6 percent of the book market, as e-books have become the preferred format for low-cost, portable reading.

Paperbacks became popular in the 1870s, mostly with middle- and working-class readers. This phenomenon sparked fear and outrage among those in the professional and educated classes, many of whom thought that reading cheap westerns and crime novels might ruin civilization. Some of the earliest paperbacks ripped off foreign writers, who were unprotected by copyright law and did not receive royalties for the books they sold in the United States. This changed with the International Copyright Law of 1891, which mandated that any work by any author could not be reproduced without the author’s permission.

The popularity of paperbacks hit a major peak in 1939 with the establishment of Pocket Books by Robert de Graff. Revolutionizing the paperback industry, Pocket Books lowered the standard book price of fifty or seventy-five cents to twenty-five cents. To accomplish this, de Graff cut bookstore discounts from 30 to 20 percent, the book distributor’s share fell from 46 to 36 percent of the cover price, and author royalty rates went from 10 to 4 percent. In its first three weeks, Pocket Books sold 100,000 books in New York City alone. Among its first titles was Wake Up and Live by Dorothea Brande, a 1936 best-seller on self-improvement that ignited an early wave of self-help books. Pocket Books also published The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie; Enough Rope, a collection of poems by Dorothy Parker; and Five Great Tragedies by Shakespeare. Pocket Books’ success spawned a series of imitators, including Dell, Fawcett, and Bantam Books.8

A major innovation of mass market paperback publishers was the instant book, a marketing strategy that involved publishing a topical book quickly after a major event occurred. Pocket Books produced the first instant book, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: A Memorial, six days after FDR’s death in 1945. Similar to made-for-TV movies and television programs that capitalize on contemporary events, instant books enabled the industry to better compete with newspapers and magazines. Such books, however, like their TV counterparts, have been accused of circulating shoddy writing, exploiting tragedies, and avoiding in-depth analysis and historical perspective. Instant books have also made government reports into best-sellers. In 1964, Bantam published The Report of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. After receiving the 385,000-word report on a Friday afternoon, Bantam staffers immediately began editing the Warren Report, and the book was produced within a week, ultimately selling over 1.6 million copies. Today, instant books continue to capitalize on contemporary events, including the inauguration of Barack Obama in 2009, the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton in 2011, and Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

Religious Books

“Religion is just so much a part of the cultural conversation these days because of global terrorism and radical Islam. People want to understand those things.”

LYNN GARRETT,RELIGION EDITOR AT PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, 2004

The best-selling book of all time is the Bible, in all its diverse versions. Over the years, the success of Bible sales has created a large industry for religious books. After World War II, sales of religious books soared. Historians attribute the sales boom to economic growth and a nation seeking peace and security while facing the threat of “godless communism” and the Soviet Union.9 By the 1960s, though, the scene had changed dramatically. The impact of the Civil Rights struggle, the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution, and the youth rebellion against authority led to declines in formal church membership. Not surprisingly, sales of some types of religious books dropped as well. To compete, many religious-book publishers extended their offerings to include serious secular titles on such topics as war and peace, race, poverty, gender, and civic responsibility.

Throughout this period of change, the publication of fundamentalist and evangelical literature remained steady. It then expanded rapidly during the 1980s, when the Republican Party began making political overtures to conservative groups and prominent TV evangelists. After a record year in 2004 (twenty-one thousand new titles), there has been a slight decline in the religious-book category. However, it continues to be an important part of the book industry, especially during turbulent social times.

Reference Books

“Wikipedia, or any free information resources, challenge reference publishers to be better than free. … It isn’t enough for a publisher to simply provide information, we have to add value.”

TOM RUSSELL, RANDOM HOUSE REFERENCE PUBLISHER, 2007

Another major division of the book industry—reference books—includes dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, almanacs, and a number of substantial volumes directly related to particular professions or trades, such as legal casebooks and medical manuals.

The two most common reference books are encyclopedias and dictionaries. The idea of developing encyclopedic writings to document the extent of human knowledge is attributed to the Greek philosopher Aristotle. The Roman citizen Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) wrote the oldest reference work still in existence, Historia Naturalis, detailing thousands of facts about animals, minerals, and plants. But it wasn’t until the early 1700s that the compilers of encyclopedias began organizing articles in alphabetical order and relying on specialists to contribute essays in their areas of interest. Between 1751 and 1771, a group of French scholars produced the first multiple-volume set of encyclopedias.

The oldest English-language encyclopedia still in production, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, was first published in Scotland in 1768. U.S. encyclopedias followed, including Encyclopedia Americana (1829), The World Book Encyclopedia (1917), and Compton’s Pictured Encyclopedia (1922). Encyclopaedia Britannica produced its first U.S. edition in 1908. This best-selling encyclopedia’s sales dwindled in the 1990s due to competition from electronic encyclopedias (like Microsoft’s Encarta), and it went digital too. Encyclopaedia Britannica and The World Book Encyclopedia (which still produces a printed set) are now the leading digital encyclopedias, although even they struggle today as young researchers increasingly rely on search engines such as Google or online resources like Wikipedia to find information (though many critics consider these sources inferior in quality).

Dictionaries have also accounted for a large portion of reference sales. The earliest dictionaries were produced by ancient scholars attempting to document specialized and rare words. During the manuscript period in the Middle Ages, however, European scribes and monks began creating glossaries and dictionaries to help people understand Latin. In 1604, a British schoolmaster prepared the first English dictionary. In 1755, Samuel Johnson produced the Dictionary of the English Language. Describing rather than prescribing word usage, Johnson was among the first to understand that language changes—that words and usage cannot be fixed for all time. In the United States in 1828, Noah Webster, using Johnson’s work as a model, published the American Dictionary of the English Language, differentiating between British and American usages and simplifying spelling (for example, colour became color and musick became music). As with encyclopedias, dictionaries have moved mostly to online formats since the 1990s, and they struggle to compete with free online or built-in word-processing software dictionaries.

University Press Books

“[University] presses are meant to be one of the few alternative sources of scholarship and information available in the United States. … Does the bargain involved in publishing commercial titles compromise that role?”

ANDRÉ SCHIFFRIN, CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, 1999

The smallest division in the book industry is the nonprofit university press, which publishes scholarly works for small groups of readers interested in intellectually specialized areas such as literary theory and criticism, history of art movements, contemporary philosophy, and the like. Professors often try to secure book contracts from reputable university presses to increase their chances for tenure, a lifetime teaching contract. Some university presses are very small, producing as few as ten titles a year. The largest—the University of Chicago Press—regularly publishes more than two hundred titles a year. One of the oldest and most prestigious presses is Harvard University Press, formally founded in 1913 but claiming roots that go back to 1640, when Stephen Daye published the first colonial book in a small shop located behind the house of Harvard’s president.

University presses have not traditionally faced pressure to produce commercially viable books, preferring to encourage books about highly specialized topics by innovative thinkers. In fact, most university presses routinely lose money and are subsidized by their university. Even when they publish more commercially accessible titles, the lack of large marketing budgets prevents them from reaching mass audiences. While large commercial trade houses are often criticized for publishing only blockbuster books, university presses often suffer the opposite criticism—that they produce mostly obscure books that only a handful of scholars read. To offset costs and increase revenue, some presses are trying to form alliances with commercial houses to help promote and produce academic books that have wider appeal.