The Structure of Ad Agencies

Traditional ad agencies, regardless of their size, generally divide the labor of creating and maintaining advertising campaigns among four departments: account planning, creative development, media coordination, and account management. Expenses incurred for producing the ads are part of a separate negotiation between the agency and the advertiser. As a result of this commission arrangement, it generally costs most large-volume advertisers no more to use an agency than it does to use their own staff.

Account Planning, Market Research, and VALS

“The best advertising artist of all time was Raphael. He had the best client—the papacy; the best art director—the College of Cardinals; and the best product—salvation. And we never disparage Raphael for working for a client or selling an idea.”

MARK FENSKE, CREATIVE DIRECTOR, N. W. AYER, 1996

The account planner’s role is to develop an effective advertising strategy by combining the views of the client, the creative team, and consumers. Consumers’ views are the most difficult to understand, so account planners coordinate market research to assess the behaviors and attitudes of consumers toward particular products long before any ads are created. Researchers may study everything from possible names for a new product to the size of the copy for a print ad. Researchers also test new ideas and products with consumers to get feedback before developing final ad strategies. In addition, some researchers contract with outside polling firms to conduct regional and national studies of consumer preferences.

Agencies have increasingly employed scientific methods to study consumer behavior. In 1932, Young & Rubicam first used statistical techniques developed by pollster George Gallup. By the 1980s, most large agencies retained psychologists and anthropologists to advise them on human nature and buying habits. The earliest type of market research, demographics, mainly studied and documented audience members’ age, gender, occupation, ethnicity, education, and income. Today, demographic data are much more specific. They make it possible to locate consumers in particular geographic regions—usually by zip code. This enables advertisers and product companies to target ethnic neighborhoods or affluent suburbs for direct mail, point-of-purchase store displays, or specialized magazine and newspaper inserts.

“Alcohol marketers appear to believe that the proto-typical college student is (1) male; (2) a nitwit; and (3) interested in nothing but booze and ‘babes.’”

MICHAEL F. JACOBSON AND LAURIE ANN MAZUR, MARKETING MADNESS, 1995

Demographic analyses provide advertisers with data on people’s behavior and social status but reveal little about feelings and attitudes. By the 1960s and 1970s, advertisers and agencies began using psychographics, a research approach that attempts to categorize consumers according to their attitudes, beliefs, interests, and motivations. Psychographic analysis often relies on focus groups, a small-group interview technique in which a moderator leads a discussion about a product or an issue, usually with six to twelve people. Because focus groups are small and less scientific than most demographic research, the findings from such groups may be suspect.

In 1978, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), now called Strategic Business Insights (SBI), instituted its Values and Lifestyles (VALS) strategy. Using questionnaires, VALS researchers measured psychological factors and divided consumers into types. VALS research assumes that not every product suits every consumer and encourages advertisers to vary their sales slants to find market niches.

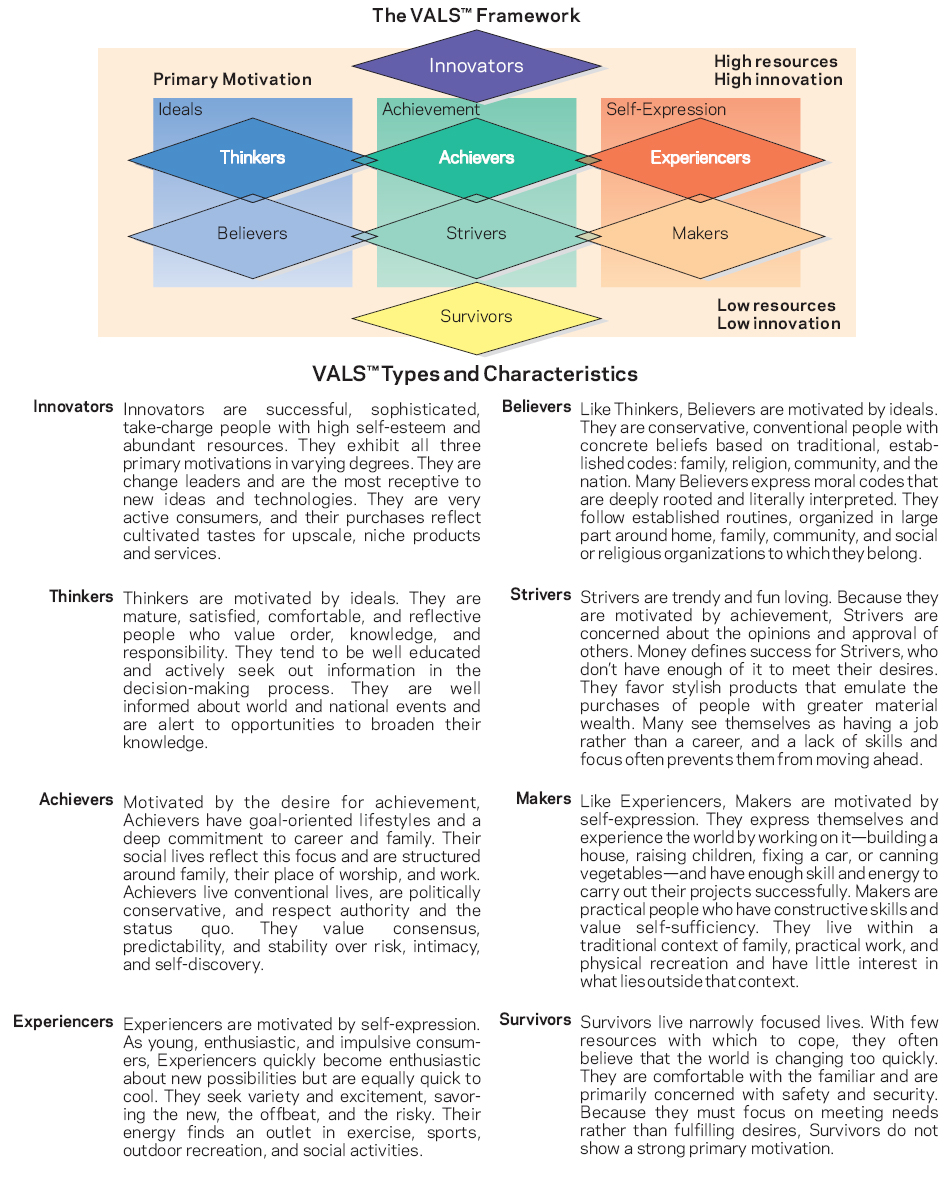

Over the years, the VALS system has been updated to reflect changes in consumer orientations (see Figure 11.3). The most recent system classifies people by their primary consumer motivations: ideals, achievement, or self-expression. The ideals-oriented group, for instance, includes thinkers—”mature, satisfied, comfortable, and reflective people who value order, knowledge, and responsibility.” VALS and similar research techniques ultimately provide advertisers with microscopic details about which consumers are most likely to buy which products.

Agencies and clients—particularly auto manufacturers—have relied heavily on VALS to determine the best placement for ads. VALS data suggest, for example, that achievers and experiencers watch more sports and news programs; these groups prefer luxury cars or sport-utility vehicles. Thinkers, on the other hand, favor TV dramas and documentaries and like the functionality of minivans or the gas efficiency of hybrids.

VALS TYPES AND CHARACTERISTICS

Source: Strategic Business Insights, 2010, http://strategicbusinessinsights.com/vals/ustypes.shtml.

VALS researchers do not claim that most people fit neatly into a category. But many agencies believe that VALS research can give them an edge in markets where few differences in quality may actually exist among top-selling brands. Consumer groups, wary of such research, argue that too many ads promote only an image and provide little information about a product’s price, its content, or the work conditions under which it was produced.

Creative Development

Teams of writers and artists—many of whom regard ads as a commercial art form—make up the nerve center of the advertising business. The creative department outlines the rough sketches for print and online ads and then develops the words and graphics. For radio, the creative side prepares a working script, generating ideas for everything from choosing the narrator’s voice to determining background sound effects. For television, the creative department develops a storyboard, a sort of blueprint or roughly drawn comic-strip version of the potential ad. For digital media, the creative team may develop Web sites, interactive tools, flash games, downloads, and viral marketing—short videos or other content that (marketers hope) quickly gains widespread attention as users share it with friends online, or by word of mouth.

“Ads seem to work on the very advanced principle that a very small pellet or pattern in a noisy, redundant barrage of repetition will gradually assert itself.”

MARSHALL MCLUHAN, UNDERSTANDING MEDIA, 1964

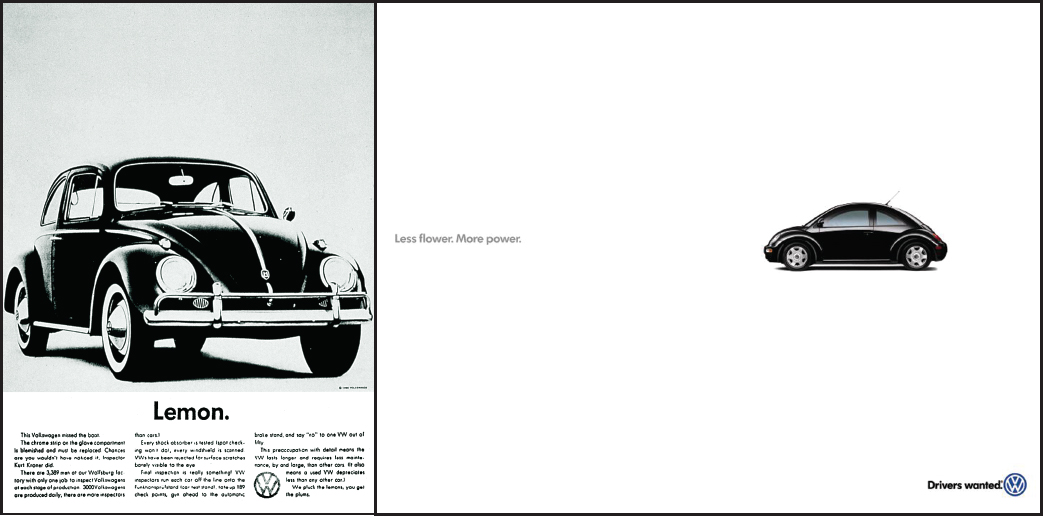

Often the creative side of the business finds itself in conflict with the research side. In the 1960s, for example, both Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) and Ogilvy & Mather downplayed research; they championed the art of persuasion and what “felt right.” Yet DDB’s simple ads for Volkswagen Beetles in the 1960s were based on weeks of intensive interviews with VW workers as well as on creative instincts. The campaign was remarkably successful in establishing the first niche for a foreign car manufacturer in the United States. Although sales of the VW “bug” had been growing before the ad campaign started, the successful ads helped Volkswagen preempt the Detroit auto industry’s entry into the small-car field.

Both the creative and the strategic sides of the business acknowledge that they cannot predict with any certainty which ads and which campaigns will succeed. Agencies say ads work best by slowly creating brand-name identities—by associating certain products over time with quality and reliability in the minds of consumers. Some economists, however, believe that much of the money spent on advertising is ultimately wasted because it simply encourages consumers to change from one brand name to another. Such switching may lead to increased profits for a particular manufacturer, but it has little positive impact on the overall economy.

Media Coordination: Planning and Placing Advertising

Ad agency media departments are staffed by media planners and media buyers: people who choose and purchase the types of media that are best suited to carry a client’s ads, reach the targeted audience, and measure the effectiveness of those ad placements. For instance, a company like Procter & Gamble, currently the world’s leading advertiser, displays its more than three hundred major brands—most of them household products like Crest toothpaste and Huggies diapers—on TV shows viewed primarily by women. To reach male viewers, however, media buyers encourage beer advertisers to spend their ad budgets on cable and network sports programming, evening talk radio, or sports magazines.

Along with commissions or fees, advertisers often add incentive clauses to their contracts with agencies, raising the fee if sales goals are met and lowering it if goals are missed. Incentive clauses can sometimes encourage agencies to conduct repetitive saturation advertising, in which a variety of media are inundated with ads aimed at target audiences. The initial Miller Lite beer campaign (“Tastes great, less filling”), which used humor and retired athletes to reach its male audience, became one of the most successful saturation campaigns in media history. It ran from 1973 to 1991 and included television and radio spots, magazine and newspaper ads, and billboards and point-of-purchase store displays. The excessive repetition of the campaign helped light beer overcome a potential image problem: being viewed as watered-down beer unworthy of “real” men.

The cost of advertising, especially on network television, increases each year. The Super Bowl remains the most expensive program for purchasing television advertising, with thirty seconds of time costing $4 million in 2013. Running a thirty-second ad during a national prime-time TV show can cost from $50,000 to more than $500,000 depending on the popularity and ratings of the program. These factors help determine where and when media buyers place ads.

Account and Client Management

Client liaisons, or account executives, are responsible for bringing in new business and managing the accounts of established clients, including overseeing budgets and the research, creative, and media planning work done on their campaigns. This department also oversees new ad campaigns in which several agencies bid for a client’s business, coordinating the presentation of a proposed campaign and various aspects of the bidding process, such as determining what a series of ads will cost a client. Account executives function as liaisons between the advertiser and the agency’s creative team. Because most major companies maintain their own ad departments to handle everyday details, account executives also coordinate activities between their agency and a client’s in-house personnel.

The advertising business is volatile, and account departments are especially vulnerable to upheavals. One industry study conducted in the mid-1980s indicated that client accounts stayed with the same agency for about seven years on average, but since the late 1980s clients have changed agencies much more often. Clients routinely conduct account reviews, the process of evaluating and reinvigorating a product’s image by reviewing an ad agency’s existing campaign or by inviting several new agencies to submit new campaign strategies, which may result in the product company switching agencies. For example, when General Motors restructured its business in 2010, it put its advertising account for Chevrolet under review. Campbell-Ewald (a subsidiary of Interpublic) had held the Chevy account since 1919, creating such campaigns as “The Heartbeat of America” and “Like a Rock,” but after the review it lost the $30 million account to Publicis.10

The New York ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach created a famous series of print and television ads for Volkswagen beginning in 1959 (below, left), and helped to usher in an era of creative advertising that combined a single-point sales emphasis with bold design, humor, and honesty. Arnold Worldwide, a Boston agency, continued the highly creative approach with its clever, award-winning “Drivers wanted” campaign for the New Beetle (below).