Critical Issues in Advertising

“Some of these companies spend more on media than they spend on the materials to make their products.”

IRWIN GOTLIEB, CEO OF WPP GROUP’S MINDSHARE, 2003

In his 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard expressed concern that advertising was manipulating helpless consumers, attacking our dignity, and invading “the privacy of our minds.”23 According to this view, the advertising industry was all-powerful. Although consumers have historically been regarded as dupes by many critics, research reveals that the consumer mind is not as easy to predict as some advertisers once thought. In the 1950s, for example, Ford could not successfully sell its midsize car, the oddly named Edsel, which was aimed at newly prosperous Ford customers looking to move up to the latest in push-button window wipers and antennas. After a splashy and expensive ad campaign, Ford sold only 63,000 Edsels in 1958 and just 2,000 in 1960, when the model was discontinued.

One of the most disastrous campaigns ever featured the now-famous “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile” spots that began running in 1989 and starred celebrities like former Beatles drummer Ringo Starr and his daughter. Oldsmobile (which became part of General Motors in 1908) and its ad agency, Leo Burnett, decided to market to a younger generation after sales declined from a high of 1.1 million vehicles in 1985 to only 715,000 in 1988. But the campaign backfired, apparently alienating its older loyal customers (who may have felt abandoned by Olds and its catchy new slogan) and failing to lure younger buyers (who probably still had trouble getting past the name “Olds”). In 2000, Oldsmobile sold only 260,000 cars, and GM phased out its Olds division by 2005.24

As these examples illustrate, most people are not easily persuaded by advertising. Over the years, studies have suggested that between 75 and 90 percent of new consumer products typically fail because they are not embraced by the buying public.25 But despite public resistance to many new products, the ad industry has made contributions, including raising the American standard of living and financing most media industries. Yet serious concerns over the impact of advertising remain. Watchdog groups worry about the expansion of advertising’s reach, and critics continue to condemn ads that stereotype or associate products with sex appeal, youth, and narrow definitions of beauty. Some of the most serious concerns involve children, teens, and health.

Children and Advertising

VideoCentral  Mass Communication

Mass Communication

Advertising and Effects on Children

Scholars and advertisers analyze the effects of advertising on children.

Discussion: In the video, some argue that using cute, kid-friendly imagery in ads can lead children to begin drinking; others dispute this claim. What do you think, and why?

Children and teenagers, living in a culture dominated by TV ads, are often viewed as “consumer trainees.” For years, groups such as Action for Children’s Television (ACT) worked to limit advertising aimed at children. In the 1980s, ACT fought particularly hard to curb program-length commercials: thirty-minute cartoon programs (such as G.I. Joe, My Little Pony and Friends, The Care Bear Family, and He-Man and the Masters of the Universe) developed for television syndication primarily to promote a line of toys. This commercial tradition continued with programs such as Pokémon and SpongeBob SquarePants.

In addition, parent groups have worried about the heavy promotion of products like sugar-coated cereals during children’s programs. Pointing to European countries, where children’s advertising is banned, these groups have pushed to minimize advertising directed at children. Congress, hesitant to limit the protection that the First Amendment offers to commercial speech, and faced with lobbying by the advertising industry, has responded weakly. The Children’s Television Act of 1990 mandated that networks provide some educational and informational children’s programming, but the act has been difficult to enforce and has done little to restrict advertising aimed at kids.

Because children and teenagers influence up to $500 billion a year in family spending—on everything from snacks to cars—they are increasingly targeted by advertisers.26 A Stanford University study found that a single thirty-second TV ad can influence the brand choices of children as young as age two. Still, methods for marketing to children have become increasingly seductive as product placement and merchandising tie-ins become more prevalent. Most recently, companies have used seemingly innocuous online games to sell products like breakfast cereal to children.

Advertising in Schools

“It isn’t enough to advertise on television…. [Y]ou’ve got to reach kids throughout the day—in school, as they’re shopping in the mall … or at the movies. You’ve got to become part of the fabric of their lives.”

CAROL HERMAN, SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, GREY ADVERTISING, 1996

A controversial development in advertising was the introduction of Channel One into thousands of schools during the 1989–90 school year. The brainchild of Whittle Communications, Channel One offered “free” video and satellite equipment (tuned exclusively to Channel One) in exchange for a twelve-minute package of current events programming that included two minutes of commercials. In 2007, Alloy Media + Marketing, a New York–based marketing company that targets young audiences, bought Channel One. In 2012, Channel One reached a captive audience of approximately six million U.S. students in eight thousand middle schools and high schools each day.

Over the years, the National Dairy Council and other organizations have also used schools to promote products, providing free filmstrips, posters, magazines, folders, and study guides adorned with corporate logos. Teachers, especially in underfunded districts, have usually been grateful for the support. Channel One, however, has been viewed as a more intrusive threat, violating the implicit cultural border between an entertainment situation (watching commercial television) and a learning situation (going to school). One study showed that schools with a high concentration of low-income students were more than twice as likely as affluent schools to receive Channel One.27

Some individual school districts have banned Channel One, as have the states of New York and California. These school systems have argued that Channel One provides students with only slight additional knowledge about current affairs; but students find the products advertised—sneakers, cereal, and soda, among others—more worthy of purchase because they are advertised in educational environments.28 A 2006 study found that students remember “more of the advertising than they do the news stories shown on Channel One.”29

Health and Advertising

Eating Disorders. Advertising has a powerful impact on the standards of beauty in our culture. A long-standing trend in advertising is the association of certain products with ultrathin female models, promoting a style of “attractiveness” that girls and women are invited to emulate. Even today, despite the popularity of fitness programs, most fashion models are much thinner than the average woman. Some forms of fashion and cosmetics advertising actually pander to individuals’ insecurities and low self-esteem by promising the ideal body. Such advertising suggests standards of style and behavior that may be not only unattainable but also harmful, leading to eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia and an increase in cosmetic surgeries.

If advertising has been criticized for promoting skeleton-like beauty, it has also been blamed for the tripling of obesity rates in the United States since the 1980s, with a record 66 percent of adult Americans identified in 2012 as overweight or obese. Corn syrup–laden soft drinks, fast food, and processed food are the staples of media ads and are major contributors to the nationwide weight problem. More troubling is that an obese nation is good for business (creating a multibillion-dollar market for diet products, exercise equipment, and self-help books), so media outlets see little reason to change current ad practices. The food and restaurant industry at first denied any connection between ads and the rise of U.S. obesity rates, instead blaming individuals who make bad choices. Increasingly, however, some fast-food chains offer healthier meals and calorie counts on various food items.

Tobacco. One of the most sustained criticisms of advertising is its promotion of tobacco con-sumption. Opponents of tobacco advertising have become more vocal in the face of grim statistics: Each year, an estimated 400,000 Americans die from diseases related to nicotine addiction and poisoning. Tobacco ads disappeared from television in 1971, under pressure from Congress and the FCC. However, over the years numerous ad campaigns have targeted teenage consumers of cigarettes. In 1988, for example, R. J. Reynolds, a subdivision of RJR Nabisco, updated its Joe Camel cartoon character, outfitting him with hipper clothes and sunglasses. Spending $75 million annually, the company put Joe on billboards and store posters and in sports stadiums and magazines. One study revealed that before 1988 fewer than 1 percent of teens under age eighteen smoked Camels. After the ad blitz, however, 33 percent of this age group preferred Camels.

“We have to sell cigarettes to your kids. We need half a million new smokers a year just to stay in business. So we advertise near schools, at candy counters.”

CALIFORNIA ANTI-CIGARETTE TV AD. TOBACCO COMPANIES FILED A FEDERAL SUIT AGAINST THE AD AND LOST WHEN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT TURNED DOWN THEIR APPEAL IN 2006

In addition to young smokers, the tobacco industry has targeted other groups. In the 1960s, for instance, the advertising campaigns for Eve and Virginia Slims cigarettes (reminiscent of ads during the suffrage movement in the early 1900s) associated their products with women’s liberation, equality, and slim fashion models. And in 1989, Reynolds introduced a cigarette called Uptown, targeting African American consumers. The ad campaign fizzled due to public protests by black leaders and government officials. When these leaders pointed to the high concentration of cigarette billboards in poor urban areas and the high mortality rates among black male smokers, the tobacco company withdrew the brand.

The government’s position regarding the tobacco industry began to change in the mid-1990s, when new reports revealed that tobacco companies had known that nicotine was addictive as early as the 1950s and had withheld that information from the public. In 1998, after four states won settlements against the tobacco industry and the remaining states threatened to bring more expensive lawsuits against the companies, the tobacco industry agreed to an unprecedented $206 billion settlement that carried significant limits on advertising and marketing tobacco products.

The agreement’s provisions banned cartoon characters in advertising, thus ending the use of the Joe Camel character; prohibited the industry from targeting young people in ads and marketing and from giving away free samples, tobacco-brand clothing, and other merchandise; and ended outdoor billboard and transit advertising. The agreement also banned tobacco company sponsorship of concerts and athletic events, and it strictly limited other corporate sponsorships by tobacco companies. These agreements, however, do not apply to tobacco advertising abroad (see “Global Village: Smoking Up the Global Market”).

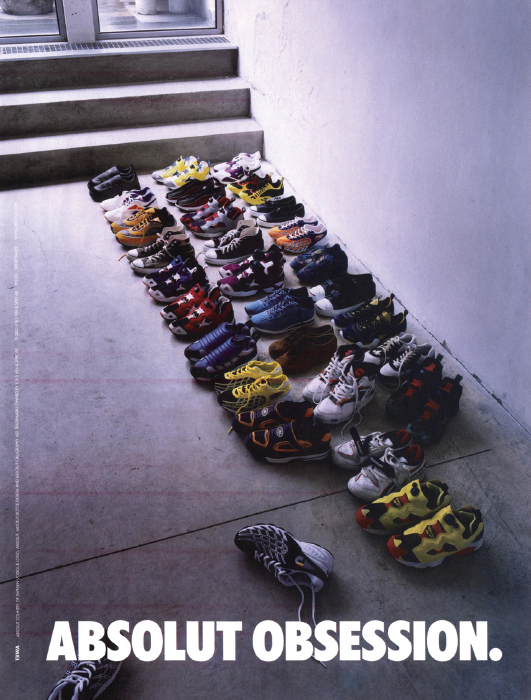

TBWA (now a unit of Omnicom) introduced Absolut Vodka’s distinctive advertising campaign in 1980. The campaign marketed a little-known Swedish vodka as an exclusive lifestyle brand, an untraditional approach that parlayed it into one of the world’s best-selling spirits. The long-running ad campaign ended in 2006, with more than 1,450 ads having maintained the brand’s premium status by referencing fashion, artists, and contemporary music.

Alcohol. Every year, about 79,000 people die from alcohol-related diseases, and another 10,000 die in car crashes involving drunk drivers. As you can guess, many of the same complaints regarding tobacco advertising are also being directed at alcohol ads. (The hard liquor industry has voluntarily banned TV and radio ads for decades.) For example, one of the most popular beer ad campaigns of the late 1990s, featuring the Budweiser frogs (which croak Bud-weis-errrr), has been accused of using cartoonlike animal characters to appeal to young viewers. In fact, the Budweiser ads would be banned under the tough standards of the tobacco settlement mentioned above, which prohibits the attribution of human characteristics to animals, plants, or other objects.

Alcohol ads have also targeted minority populations. Malt liquors, which contain higher concentrations of alcohol than beers do, have been touted in high-profile television ads for such labels as Colt 45 and Magnum. There is also a trend toward marketing high-end liquors to African American and Hispanic male populations. In a recent marketing campaign, Hennessy targeted young African American men with ads featuring hip-hop star Nas and sponsored events in Times Square and at the Governors Ball and Coachella music festivals. Hennessy also sponsored VIP parties with Latino deejays and hip-hop acts in Miami and Houston.

College students, too, have been heavily targeted by alcohol ads, particularly by the beer industry. Although colleges and universities have outlawed “beer bashes” hosted and supplied directly by major brewers, both Coors and Miller still employ student representatives to help “create brand awareness.” These students notify brewers of special events that might be sponsored by and linked to a specific beer label. The images and slogans in alcohol ads often associate the products with power, romance, sexual prowess, or athletic skill. In reality, though, alcohol is a chemical depressant; it diminishes athletic ability and sexual performance, triggers addiction in roughly 10 percent of the U.S. population, and factors into many domestic abuse cases. A national study demonstrated “that young people who see more ads for alcoholic beverages tend to drink more.”30

Tennis champion Serena Williams recently endorsed the sleep supplement “Sleep Sheets,” an over-the-counter sleep aid that promises to combat insomnia and promote natural sleep. Although it is available without a prescription, Williams’s vigorous ad campaign for the supplement, which she co-owns, attests to the persistence of prescription drug ads and the vulnerability of their audience.

Prescription Drugs.Another area of concern is the recent surge in prescription drug advertising. Spending on direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs increased from $266 million in 1994 to $5.3 billion in 2007—largely because of growth in television advertising, which today accounts for about two-thirds of such ads. The ads have made household names of prescription drugs such as Nexium, Claritin, Paxil, and Viagra. The ads are also very effective: Another survey found that nearly one in three adults has talked to a doctor and one in eight has received a prescription in response to seeing an ad for a prescription drug.31 But between 2007 and 2011, direct-to-consumer TV advertising for prescription drugs dropped 23 percent—from $3.1 billion in 2007 to $2.3 billion in 2011—in part due to doctors’ concerns about being pressured by patients who see the TV ads for new drugs and due to notable recalls of heavily advertised drugs like Vioxx, a pain reliever that was later found to have harsh side effects. Still, in 2011, Pfizer spent $156 million on TV ads for Lipitor (a cholesterol-lowering drug that reduces the risk of heart attack and stroke), the highest amount spent for any prescription drug that year.32

The tremendous growth of prescription drug ads brings the potential for false and misleading claims, particularly because a brief TV advertisement can’t possibly communicate all of the relevant cautionary information. More recently, direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising has appeared in text messages and on Facebook. Pharmaceutical companies have also engaged in “disease awareness” campaigns to build markets for their products. In 2012, the United States and New Zealand were the only two nations that allow prescription drugs to be advertised directly to consumers.