Advertising in the 1800s

The first full-service modern ad agency, N. W. Ayer & Son, worked primarily for advertisers and product companies rather than for newspapers. Opening in 1869 in Philadelphia, the agency helped create, write, produce, and place ads in selected newspapers and magazines. The traditional payment structure at this time had the agency collecting a fee from its advertising client for each ad placed; the fee covered the price that each media outlet charged for placement of the ad, plus a 15 percent commission for the agency. The more ads an agency placed, the larger the agency’s revenue. Thus agencies had little incentive to buy fewer ads on behalf of their clients. Nowadays, however, many advertising agencies work for a flat fee, and some will agree to be paid on a performance basis.

Trademarks and Packaging

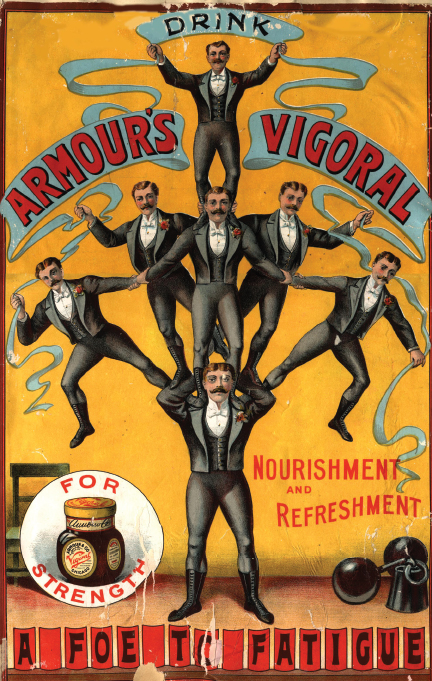

Unregulated patent medicines, such as the one represented in this ad, created a bonanza for nineteenth-century print media in search of advertising revenue. After several muckraking magazine reports about deceptive patent medicine claims, Congress created the Food and Drug Administration in 1906.

During the mid-1800s, most manufacturers served retail store owners, who usually set their own prices by purchasing goods in large quantities. Manufacturers, however, came to realize that if their products were distinctive and associated with quality, customers would ask for them by name. This would allow manufacturers to dictate prices without worrying about being undersold by stores’ generic products or bulk items. Advertising let manufacturers establish a special identity for their products, separate from those of their competitors.

Like many ads today, nineteenth-century advertisements often created the impression of significant differences among products when in fact very few differences actually existed. But when consumers began demanding certain products—either because of quality or because of advertising—manufacturers were able to raise the prices of their goods. With ads creating and maintaining brand-name recognition, retail stores had to stock the desired brands.

One of the first brand names, Smith Brothers, has been advertising cough drops since the early 1850s. Quaker Oats, the first cereal company to register a trademark, has used the image of William Penn, the Quaker who founded Pennsylvania in 1681, to project a company image of honesty, decency, and hard work since 1877. Other early and enduring brands include Campbell Soup, which came along in 1869; Levi Strauss overalls in 1873; Ivory Soap in 1879; and Eastman Kodak film in 1888. Many of these companies packaged their products in small quantities, thereby distinguishing them from the generic products sold in large barrels and bins.

Product differentiation associated with brand-name packaged goods represents the single biggest triumph of advertising. Studies suggest that although most ads are not very effective in the short run, over time they create demand by leading consumers to associate particular brands with quality. Not surprisingly, building or sustaining brand-name recognition is the focus of many product-marketing campaigns. But the costs that packaging and advertising add to products generate many consumer complaints. The high price of many contemporary products results from advertising costs. For example, designer jeans that cost $150 (or more) today are made from roughly the same inexpensive denim that has outfitted farm workers since the 1800s. The difference now is that more than 90 percent of the jeans’ cost goes toward advertising and profit.

Patent Medicines and Department Stores

“Consumption, Asthma, Bronchitis, Deafness, cured at HOME!”

AD FOR CARBOLATE OF TAR INHALANTS, 1883

By the end of the 1800s, patent medicines and department stores accounted for half of the revenues taken in by ad agencies. Meanwhile, one-sixth of all print ads came from patent medicine and drug companies. Such ads ensured the financial survival of numerous magazines as “the role of the publisher changed from being a seller of a product to consumers to being a gatherer of consumers for the advertisers.”6 Bearing names like Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, Dr. Lin’s Chinese Blood Pills, and William Radam’s Microbe Killer, patent medicines were often made with water and 15 to 40 percent concentrations of ethyl alcohol. One patent medicine—Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup—actually contained morphine. Powerful drugs in these medicines explain why people felt “better” after taking them; at the same time, they triggered lifelong addiction problems for many customers.

Many contemporary products, in fact, originated as medicines. Coca-Cola, for instance, was initially sold as a medicinal tonic and even contained traces of cocaine until 1903, when it was replaced by caffeine. Early Post and Kellogg’s cereal ads promised to cure stomach and digestive problems. Many patent medicines made outrageous claims about what they could cure, leading to increased public cynicism. As a result, advertisers began to police their ranks and develop industry codes to restore customer confidence. Partly to monitor patent medicine claims, the Federal Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906.

Along with patent medicines, department store ads were also becoming prominent in newspapers and magazines. By the early 1890s, more than 20 percent of ad space was devoted to department stores. At the time, these stores were frequently criticized for undermining small shops and businesses, where shopkeepers personally served customers. The more impersonal department stores allowed shoppers to browse and find brand-name goods themselves. Because these stores purchased merchandise in large quantities, they could generally sell the same products for less. With increased volume and less money spent on individualized service, department store chains, like Target and Walmart today, undercut small local stores and put more of their profits into ads.

Advertising’s Impact on Newspapers

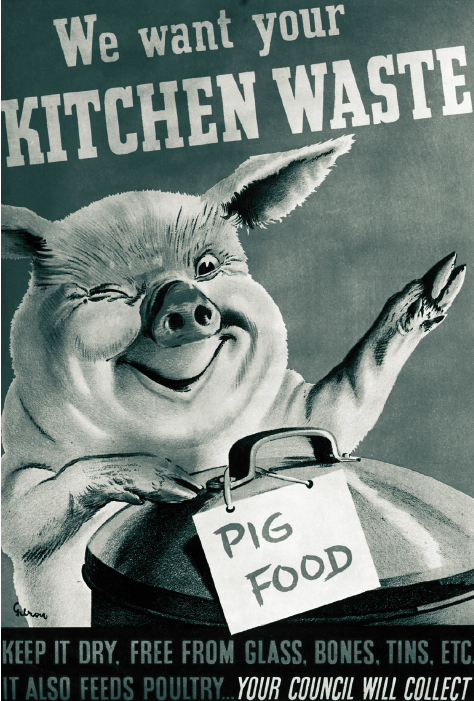

During World War II, the federal government engaged the advertising industry to create messages to support the U.S. war effort. Advertisers promoted the sale of war bonds, conservation of natural resources such as tin and gasoline, and even saving kitchen waste so it could be fed to farm animals.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, “continuous-process machinery” kept company factories operating at peak efficiency, helping to produce an abundance of inexpensive packaged consumer goods.7 The companies that produced those goods—Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, Heinz, Borden, Pillsbury, Eastman Kodak, Carnation, and American Tobacco—were some of the first to advertise, and they remain major advertisers today (although many of these brand names have been absorbed by larger conglomerates).

The demand for newspaper advertising by product companies and retail stores significantly changed the ratio of copy at most newspapers. While newspapers in the mid-1880s featured 70 to 75 percent news and editorial material and only 25 to 30 percent advertisements, by the early 1900s more than half the space in daily papers was devoted to advertising. However, the recent recession hit newspapers hard: Their advertising revenue is expected to decline from a peak of $49 billion in 2005 to an estimated $22.3 billion by 2014—a loss of 44 percent—as car, real estate, and help-wanted ads fell significantly.8 For many papers, fewer ads meant smaller papers, not more room for articles.