The Birth of Modern Public Relations

By the early 1900s, reporters and muckraking journalists began investigating the promotional practices behind many companies. As an informed citizenry paid more attention, it became more difficult for large firms to fool the press and mislead the public. With the rise of the middle class, increasing literacy among the working classes, and the spread of information through print media, democratic ideals began to threaten the established order of business and politics—and the elite groups who managed them. Two pioneers of public relations—Ivy Lee and Edward Bernays—emerged in this atmosphere to popularize an approach that emphasized shaping the interpretation of facts and “engineering consent.”

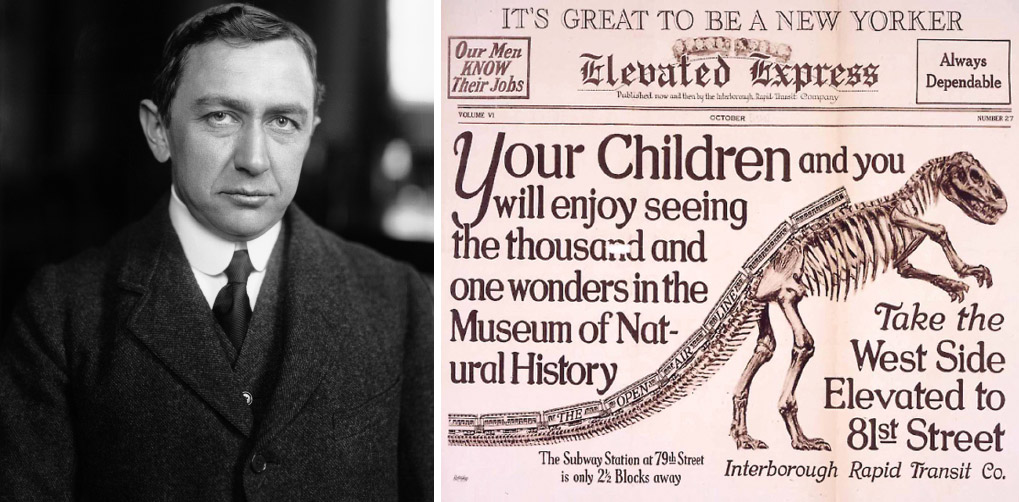

Ivy Ledbetter Lee

“Since crowds do not reason, they can only be organized and stimulated through symbols and phrases.”

IVY LEE, 1917

Most nineteenth-century corporations and manufacturers cared little about public sentiment. By the early 1900s, though, executives realized that their companies could sell more products if they were associated with positive public images and values. Into this public space stepped Ivy Ledbetter Lee, considered one of the founders of modern public relations. Lee understood that the public’s attitude toward big corporations had changed. He counseled his corporate clients that honesty and directness were better PR devices than the deceptive practices of the 1800s, which had fostered suspicion and an anti–big-business sentiment.

A minister’s son, an economics student at Princeton University, and a former reporter, Lee opened one of the first PR firms in the early 1900s with George Park. Lee quit the firm in 1906 to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which, following a rail accident, hired him to help downplay unfavorable publicity. Lee’s advice, however, was that Penn Railroad admit its mistake, vow to do better, and let newspapers in on the story. These suggestions ran counter to the then–standard practice of hiring press agents to manipulate the media, yet Lee argued that an open relationship between business and the press would lead to a more favorable public image. In the end, Penn and subsequent clients, notably John D. Rockefeller, adopted Lee’s successful strategies.

By the 1880s, Rockefeller controlled 90 percent of the nation’s oil industry and suffered from periodic image problems, particularly after Ida Tarbell’s powerful muckraking series about the ruthless business tactics practiced by Rockefeller and his Standard Oil Company appeared in McClure’s Magazine in 1904. The Rockefeller and Standard Oil reputations reached a low point in April 1914 when tactics to stop union organizing erupted in tragedy at a coal company in Ludlow, Colorado. During a violent strike, fifty-three workers and their family members, including thirteen women and children, died.

Lee was hired to contain the damaging publicity fallout. He immediately distributed a series of “fact” sheets to the press, telling the corporate side of the story and discrediting the tactics of the United Mine Workers, who organized the strike. As he had done for Penn Railroad, Lee also brought in the press and staged photo opportunities. John D. Rockefeller Jr., who now ran the company, donned overalls and a miner’s helmet and posed with the families of workers and union leaders. This was probably the first use of a PR campaign in a labor–management dispute. Over the years, Lee completely transformed the wealthy family’s image, urging the discreet Rockefellers to publicize their charitable work. To improve his image, the senior Rockefeller took to handing out dimes to children wherever he went—a strategic ritual that historians attribute to Lee.

Called “Poison Ivy” by critics within the press and corporate foes, Lee had a complex understanding of facts. For Lee, facts were elusive and malleable, begging to be forged and shaped. In the Ludlow case, for instance, Lee noted that the women and children who died while retreating from the charging company-backed militia had overturned a stove, which caught fire and caused their deaths. His PR fact sheet implied that they had, in part, been victims of their own carelessness.

Edward Bernays

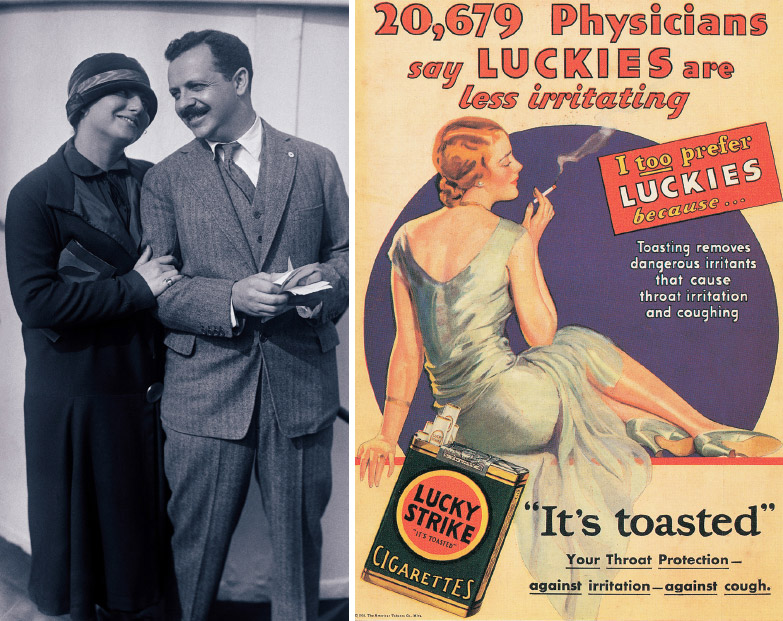

The nephew of Sigmund Freud, former reporter Edward Bernays inherited the public relations mantle from Ivy Lee. Beginning in 1919 when he opened his own office, Bernays was the first person to apply the findings of psychology and sociology to public relations, referring to himself as a “public relations counselor” rather than a “publicity agent.” Over the years, Bernays’s client list included General Electric, the American Tobacco Company, General Motors, Good Housekeeping and Time magazines, Procter & Gamble, RCA, the government of India, the city of Vienna, and President Coolidge.

Bernays also worked for the Committee on Public Information (CPI) during World War I, developing propaganda that supported America’s entry into that conflict and promoting the image of President Woodrow Wilson as a peacemaker. Both efforts were among the first full-scale governmental attempts to mobilize public opinion. In addition, Bernays made key contributions to public relations education, teaching the first class called “public relations”—at New York University in 1923—and writing the field’s first textbook, Crystallizing Public Opinion. For many years, his definition of PR was the standard: “Public relations is the attempt, by information, persuasion, and adjustment, to engineer public support for an activity, cause, movement, or institution.”11

In the 1920s, Bernays was hired by the American Tobacco Company to develop a campaign to make smoking more publicly acceptable for women (similar campaigns are under way today in countries like China). Among other strategies, Bernays staged an event: placing women smokers in New York’s 1929 Easter parade. He labeled cigarettes “torches of freedom” and encouraged women to smoke as a symbol of their newly acquired suffrage and independence from men. He also asked the women he placed in the parade to contact newspaper and newsreel companies in advance—to announce their symbolic protest. The campaign received plenty of free publicity from newspapers and magazines. Within weeks of the parade, men-only smoking rooms in New York theaters began opening up to women.

Through much of his writing, Bernays suggested that emerging freedoms threatened the established hierarchical order. He thought it was important for experts and leaders to control the direction of American society: “The duty of the higher strata of society—the cultivated, the learned, the expert, the intellectual—is therefore clear. They must inject moral and spiritual motives into public opinion.”12 For the cultural elite to maintain order and control, they would have to win the consent of the larger public. As a result, he termed the shaping of public opinion through PR as the “engineering of consent.” Like Ivy Lee, Bernays thought that public opinion was malleable and not always rational: In the hands of the right experts, leaders, and PR counselors, public opinion could be shaped into forms people could rally behind.13 However, journalists like Walter Lippmann, who wrote the famous book Public Opinion in 1922, worried that PR professionals with hidden agendas, rather than journalists with professional detachment, held too much power over American public opinion.

Throughout Bernays’s most active years, his business partner and later his wife, Doris Fleischman, worked with him on many of his campaigns as a researcher and coauthor. Beginning in the 1920s, she was one of the first women to work in public relations, and she introduced PR to America’s most powerful leaders through a pamphlet she edited called Contact. Because she opened up the profession to women from its inception, PR emerged as one of the few professions— apart from teaching and nursing—accessible to women who chose to work outside the home at that time. Today, women outnumber men by more than three to one in the profession.