Performing Public Relations

“It was the astounding success of propaganda during the war which opened the eyes of the intelligent few in all departments of life to the possibilities of regimenting the public mind.”

EDWARD BERNAYS, PROPAGANDA, 1928

Public relations, like advertising, pays careful attention to the needs of its clients—politicians, small businesses, industries, and nonprofit organizations—and to the perspectives of its targeted audiences: consumers and the general public, company employees, shareholders, media organizations, government agencies, and community and industry leaders. To do so, PR involves providing a multitude of services, including publicity, communication, public affairs, issues management, government relations, financial PR, community relations, industry relations, minority relations, advertising, press agentry, promotion, media relations, social networking, and propaganda. This last service, propaganda, is communication strategically placed, either as advertising or as publicity, to gain public support for a special issue, program, or policy, such as a nation’s war effort.

In addition, PR personnel (both PR technicians, who handle daily short-term activities, and PR managers, who counsel clients and manage activities over the long term) produce employee newsletters, manage client trade shows and conferences, conduct historical tours, appear on news programs, organize damage control after negative publicity, analyze complex issues and trends that may affect a client’s future, manage Twitter accounts, and much more. Basic among these activities, however, are formulating a message through research, conveying the message through various channels, sustaining public support through community and consumer relations, and maintaining client interests through government relations.

Research: Formulating the Message

Appealing to the eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old target age group, the interactive Web site for the Department of Defense’s “That Guy!” anti-binge-drinking campaign uses humorous terms like “Sloberus SweaToomuch” and “Drunkus Obnoxious” to describe the stages of intoxication.

Before anything else begins, one of the most essential practices in the PR profession is doing research. Just as advertising is driven today by demographic and psychographic research, PR uses similar strategies to project messages to appropriate audiences. Because it has historically been difficult to determine why particular PR campaigns succeed or fail, research has become the key ingredient in PR forecasting. Like advertising, PR makes use of mail, telephone, and Internet surveys and focus group interviews—as well as social media analytic tools such as BlogPulse, Trendrr, or Twitalyzer—to get a fix on an audience’s perceptions of an issue, policy, program, or client’s image.

Research also helps PR firms focus the campaign message. For example, in 2006 the Department of Defense hired the PR firm Fleishman-Hillard International Communications to help combat the rising rates of binge drinking among junior enlisted military personnel. The firm first verified its target audience by researching the problem, finding from the Department of Defense’s triennial Health Related Behaviors Survey that eighteen– to twenty-four-year-old servicemen had the highest rates of binge drinking. It then conducted focus groups to refine the tone of its antidrinking message, and developed and tested its Web site for usability. The finalized campaign concept and message—”Don’t Be That Guy!”—has been successful: It has shifted binge drinkers’ attitudes toward less harmful drinking behaviors through a Web site (www.thatguy.com) and multimedia campaign that combines humorous videos, games, and cartoons with useful resources. By 2012, the campaign had been implemented in over eight hundred military locations across twenty-three countries and the award-winning Web site had been viewed by approximately 1.3 million visitors.15

Conveying the Message

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A PRESS RELEASE AND A NEWS STORY

News reports can be heavily dependent on public relations for story ideas and content. At right above is a press release written by the Office of University Relations at University of Northern Iowa about First Lady Michelle Obama speaking at the 2011 spring commencement ceremony. The other two images show the Web and print news articles inspired by the release.

One of the chief day-to-day functions in public relations is creating and distributing PR messages for the news media or the public. There are several possible message forms, including press releases, VNRs, and various online options.

Press releases, or news releases, are announcements written in the style of news reports that give new information about an individual, a company, or an organization and pitch a story idea to the news media. In issuing press releases, PR agents hope that their client information will be picked up by the news media and transformed into news reports. Through press releases, PR firms manage the flow of information, controlling which media get what material in which order. (A PR agent may even reward a cooperative reporter by strategically releasing information.) News editors and broadcasters sort through hundreds of releases daily to determine which ones contain the most original ideas or are the most current. Most large media institutions rewrite and double-check the releases, but small media companies often use them verbatim because of limited editorial resources. Usually, the more closely a press release resembles actual news copy, the more likely it is to be used. (See Figure 12.2.)

Since the introduction of portable video equipment in the 1970s, PR agencies and departments have also been issuing video news releases (VNRs)—thirty- to ninety-second visual press releases designed to mimic the style of a broadcast news report. Although networks and large TV news stations do not usually broadcast VNRs, news stations in small TV markets regularly use material from VNRs. On occasion, news stations have been criticized for using video footage from a VNR without acknowledging the source. In 2005, the FCC mandated that broadcast stations and cable operators must disclose the source of the VNRs that they air. As with press releases, VNRs give PR firms some control over what constitutes “news” and a chance to influence what the general public thinks about an issue, a program, or a policy.

The equivalent of VNRs for nonprofits are public service announcements (PSAs): fifteen- to sixty-second audio or video reports that promote government programs, educational projects, volunteer agencies, or social reform. As part of their requirement to serve the public interest, broadcasters have been encouraged to carry free PSAs. Since the deregulation of broadcasting began in the 1980s, however, there has been less pressure and no minimum obligation for TV and radio stations to air PSAs. When PSAs do run, they are frequently scheduled between midnight and 6 A.M., a less commercially valuable time slot.

Today, the Internet is an essential avenue for transmitting PR messages. Companies upload or e-mail press releases, press kits, and VNRs for targeted groups. Social media has also transformed traditional PR communications. For example, a social media press release pulls together “remixable” multimedia elements such as text, graphics, video, podcasts, and hyperlinks, giving journalists ample material to develop their own stories. (See “Case Study: Social Media Transform the Press Release,”.)

Media Relations

PR managers specializing in media relations promote a client or an organization by securing publicity or favorable coverage in the news media. This often requires an in-house PR person to speak on behalf of an organization or to direct reporters to experts who can provide information. Media-relations specialists also perform damage control or crisis management when negative publicity occurs. Occasionally, in times of crisis—such as a scandal at a university or a safety recall by a car manufacturer—a PR spokesperson might be designated as the only source of information available to news media. Although journalists often resent being cut off from higher administrative levels and leaders, the institution or company wants to ensure that rumors and inaccurate stories do not circulate in the media. In these situations, a game often develops between PR specialists and the media in which reporters attempt to circumvent the spokesperson and induce a knowledgeable insider to talk off the record, providing background details without being named directly as a source.

PR agents who specialize in media relations also recommend advertising to their clients when it seems appropriate. Unlike publicity, which is sometimes outside a PR agency’s control, paid advertising may help to focus a complex issue or a client’s image. Publicity, however, carries the aura of legitimate news and thus has more credibility than advertising. In addition, media specialists cultivate associations with editors, reporters, freelance writers, and broadcast news directors to ensure that press releases or VNRs are favorably received. (See “Examining Ethics: What Does It Mean to Be Green?”.)

Special Events and Pseudo-Events

Another public relations practice involves coordinating special events to raise the profile of corporate, organizational, or government clients. Since 1967, for instance, the city of Milwaukee has run Summerfest, a ten-day music and food festival that attracts about a million people each year and now bills itself as “The World’s Largest Music Festival.” As the festival’s popularity grew, various companies sought to become sponsors of the event. Today, Milwaukee’s Miller Brewing Company sponsors one of the music festival’s stages, which carries the Miller name and promotes Miller Lite as the “official beer” of the festival. Briggs & Stratton and Harley Davidson are also among the local companies that sponsor stages at the event. In this way, all three companies receive favorable publicity by showing a commitment to the city in which their corporate headquarters are located.16

More typical of special-events publicity is a corporate sponsor aligning itself with a cause or an organization that has positive stature among the general public. For example, John Hancock Financial has been the primary sponsor of the Boston Marathon since 1986 and funds the race’s prize money. The company’s corporate communications department also serves as the PR office for the race, operating the pressroom and creating the marathon’s media guide and other press materials. Eighteen other sponsors, including Adidas, Gatorade, PowerBar, and JetBlue Airways, also pay to affiliate themselves with the Boston Marathon. At the local level, companies often sponsor a community parade or a charitable fund-raising activity.

In contrast to a special event, a pseudo-event is any circumstance created for the sole purpose of gaining coverage in the media. Historian Daniel Boorstin coined the term in his influential book The Image when pointing out the key contributions of PR and advertising in the twentieth century. Typical pseudo-events are press conferences, TV and radio talk show appearances, or any other staged activity aimed at drawing public attention and media coverage. The success of such events depends on the participation of clients, sometimes on paid performers, and especially on the media’s attention to the event. In business, pseudo-events extend back at least as far as P. T. Barnum’s publicity stunts, such as parading Jumbo the Elephant across the Brooklyn Bridge in the 1880s. In politics, Theodore Roosevelt’s administration set up the first White House pressroom and held the first presidential press conferences in the early 1900s. By the 2000s, presidential pseudo-events involved a multimillion-dollar White House Communications Office. One of the most successful pseudo-events in recent years was a record-breaking space diving project. On October 14, 2012, a helium balloon took Austrian skydiver Felix Baumgartner twenty-four miles into the stratosphere. He jumped from the capsule and went into a free dive for about four minutes, reaching a speed of 833.9 mph before deploying his parachute. Red Bull sponsored the project, which took more than five years of preparation.

As powerful companies, savvy politicians, and activist groups became aware of the media’s susceptibility to pseudo-events, these activities proliferated. For example, to get free publicity, companies began staging press conferences to announce new product lines. During the 1960s, antiwar and Civil Rights protesters began their events only when the news media were assembled. One anecdote from that era aptly illustrates the principle of a pseudo-event: A reporter asked a student leader about the starting time for a particular protest; the student responded, “When can you get here?” Today, politicians running for office are particularly adept at scheduling press conferences and interviews to take advantage of TV’s appetite for live remote feeds and breaking news.

Community and Consumer Relations

Another responsibility of PR is to sustain goodwill between an agency’s clients and the public. The public is often seen as two distinct audiences: communities and consumers.

Companies have learned that sustaining close ties with their communities and neighbors not only enhances their image and attracts potential customers but also promotes the idea that the companies are good citizens. As a result, PR firms encourage companies to participate in community activities such as hosting plant tours and open houses, making donations to national and local charities, and participating in town events like parades and festivals. In addition, more progressive companies may also get involved in unemployment and job-retraining programs, or donate equipment and workers to urban revitalization projects such as Habitat for Humanity.

In terms of consumer relations, PR has become much more sophisticated since 1965, when Ralph Nader’s groundbreaking book, Unsafe at Any Speed, revealed safety problems concerning the Chevrolet Corvair. Not only did Nader’s book prompt the discontinuance of the Corvair line; it also lit the fuse that ignited a vibrant consumer movement. After the success of Nader’s book, along with a growing public concern over corporate mergers and their lack of accountability to the public, consumers became less willing to readily accept the claims of corporations. As a result of the consumer movement, many newspapers and TV stations hired consumer reporters to track down the sources of customer complaints and embarrass companies by putting them in the media spotlight. Public relations specialists responded by encouraging companies to pay more attention to customers, establish product service and safety guarantees, and ensure that all calls and mail from customers were answered promptly. Today, PR professionals routinely advise clients that satisfied customers mean not only repeat business but also new business, based on a strong word-of-mouth reputation about a company’s behavior and image.

Government Relations and Lobbying

“I get in a lot of trouble if I’m quoted, especially if the quotes are accurate.”

A CONGRESSIONAL STAFF PERSON, EXPLAINING TO THE WALL STREET JOURNAL WHY HE CAN SPEAK ONLY “OFF THE RECORD,” 1999

While sustaining good relations with the public is a priority, so is maintaining connections with government agencies that have some say in how companies operate in a particular community, state, or nation. Both PR firms and the PR divisions within major corporations are especially interested in making sure that government regulation neither becomes burdensome nor reduces their control over their businesses.

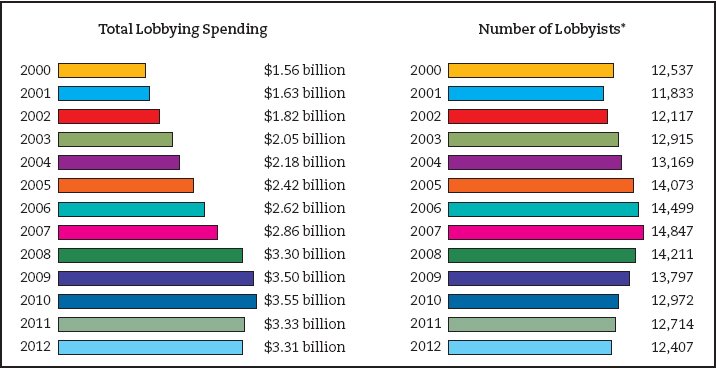

Government PR specialists monitor new and existing legislation, create opportunities to ensure favorable publicity, and write press releases and direct-mail letters to persuade the public about the pros and cons of new regulations. In many industries, government relations has developed into lobbying: the process of attempting to influence lawmakers to support and vote for an organization’s or industry’s best interests. In seeking favorable legislation, some lobbyists contact government officials on a daily basis. In Washington, D.C., alone, there are about thirteen thousand registered lobbyists—and thousands more government-relations workers who aren’t required to register under federal disclosure rules. Lobbying expenditures targeting the federal government rose above $3.3 billion in 2011, up from $1.63 billion ten years earlier.17 (See Figure 12.3.)

Lobbying can often lead to ethical problems, as in the case of earmarks and astroturf lobbying. Earmarks are specific spending directives that are slipped into bills to accommodate the interests of lobbyists and are often the result of political favors or outright bribes. In 2006, lobbyist Jack Abramoff (dubbed “The Man Who Bought Washington” in Time) and several of his associates were convicted of corruption related to earmarks, leading to the resignation of leading House members and a decline in the use of earmarks.

TOTAL LOBBYING SPENDING AND NUMBER OF LOBBYISTS (2000–2012)

Note: FIGUREs on this page are calculations by the Center for Responsive Politics based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records, accessed August 8, 2013, www.opensecrets.org/lobby.

*The number of unique, registered lobbyists who have actively lobbied.

Astroturf lobbying is phony grassroots public-affairs campaigns engineered by public relations firms. PR firms deploy massive phone banks and computerized mailing lists to drum up support and create the impression that millions of citizens back their client’s side of an issue. For instance, the Center for Consumer Freedom (CCF), an organization that appears to serve the interests of consumers, is actually a creation of the Washington, D.C.–based PR firm Berman & Co. and is funded by the restaurant, food, alcohol, and tobacco industries. According to Sourcewatch.org, which tracks astroturf lobbying, “Anyone who criticizes tobacco, alcohol, fatty foods or soda pop is likely to come under attack from CCF.”

“We’re proud of the work we do for Saudi Arabia. It’s a very challenging assignment.”

MIKE PETRUZZELLO, QORVIS COMMUNICATIONS

Public relations firms do not always work for the interests of corporations, however. They also work for other clients, including consumer groups, labor unions, professional groups, religious organizations, and even foreign governments. In 2005, for example, the California Center for Public Health Advocacy, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization, hired Brown-Miller Communications, a small California PR firm, to rally support for landmark legislation that would ban junk food and soda sales in the state’s public schools. Brown-Miller helped state legislators see obesity not as a personal choice issue but as a public policy issue, cultivated the editorial support of newspapers to compel legislators to sponsor the bills, and ultimately succeeded in getting a bill passed.

Presidential administrations also use public relations—with varying degrees of success—to support their policies. From 2002 to 2008, the Bush administration’s Defense Department operated a “Pentagon Pundit” program, secretly cultivating more than seventy retired military officers to appear on radio and television talk shows and shape public opinion about the Bush agenda. In 2008, the New York Times exposed the unethical program and its story earned a Pulitzer Prize.18 The Obama administration pledged to be more transparent. In 2010, the Columbia Journalism Review lauded the administration for “significant progress on transparency and access issues” but gave them poor grades on state secrets, online data, and background briefings.19