Deregulation Trumps Regulation

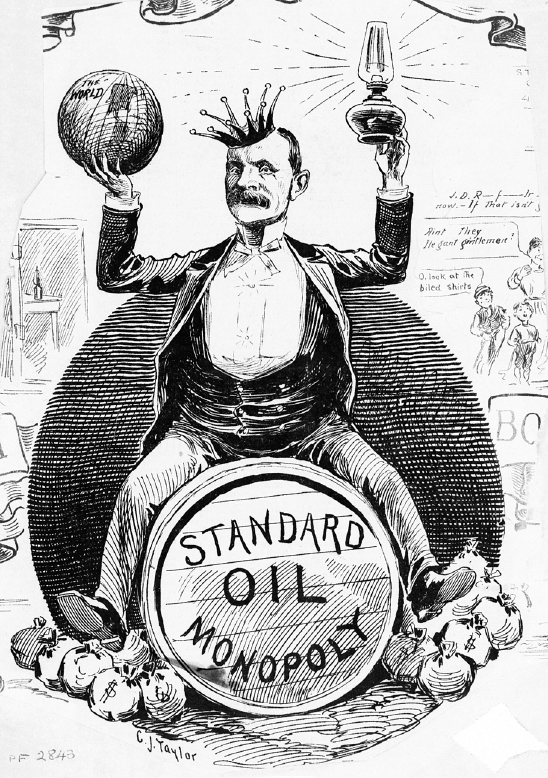

During the rise of industry in the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs such as John D. Rockefeller in oil, Cornelius Vanderbilt in shipping and railroads, and Andrew Carnegie in steel created monopolies in their respective industries. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, outlawing the monopoly practices and corporate trusts that often fixed prices to force competitors out of business. In 1911, the government used this act to break up both the American Tobacco Company and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, which was divided into thirty smaller competing firms.

In 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, prohibiting manufacturers from selling only to dealers and contractors who agreed to reject the products of business rivals. The Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 further strengthened antitrust rules by limiting any corporate mergers and joint ventures that reduced competition. Today, these laws are enforced by the Federal Trade Commission and the antitrust division of the Department of Justice.

During the late 1800s, John D. Rockefeller Sr., considered the richest businessman in the world, controlled more than 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining business. But antitrust regulations were used in 1911 to bust Rockefeller’s powerful Standard Oil into more than thirty separate companies. He later hired PR guru Ivy Lee to refashion his negative image as a greedy corporate mogul.

The Escalation of Deregulation

“Big is bad if it stifles competition … but big is good if it produces quality programs.”

MICHAEL EISNER, THEN-CEO,DISNEY, 1995

Until the banking, credit, and mortgage crises erupted in fall 2008, government regulation had often been denounced as a barrier to the more flexible flow of capital. Although the administration of President Carter (1977–81) actually initiated deregulation, under President Reagan (1981–89) most controls on business were drastically weakened. Deregulation led to easier mergers, corporate diversifications, and increased tendencies in some sectors toward oligopolies (especially in airlines, energy, communications, and finance).9 This deregulation and decline of government oversight sometimes led to severe consequences, such as the collapse of Enron in 2001, the fraud cases at telecommunications firm WorldCom and cable company Adelphia in 2005, and the widespread financial crises that began in 2008 and set off a worldwide recession.

In the broadcast industry, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (under President Clinton) lifted most restrictions on how many radio and TV stations one corporation could own. As a result, radio and television ownership became increasingly consolidated. The 1996 act further welcomed the seven powerful regional telephone companies, known as Baby Bells (resulting from the mid-1980s breakup of the AT&T telephone monopoly), into the cable TV business. In addition, cable operators regained the right to freely raise their rates and were authorized to compete in the local telephone business. At the time, some economists thought the new competition would lower consumer prices. Others predicted more mergers and an oligopoly in which a few mega-corporations would control most of the wires entering a home and dictate pricing.

As it turned out, part of each prediction occurred. The price of basic cable service more than doubled between 1996 and 2012, from $24.48 to $61.63 per month.10 At the same time, the cost of a monthly telephone landline increased only about 20 percent, in part because a growing percentage of households replaced their landlines with mobile phones. Increasingly, companies like Comcast and AT&T try to corner all of the key communications systems by “bundling” multiple services—including digital cable television, high-speed Internet, home telephone, and wireless.

Deregulation Continues Today

“It’s a small world, after all.”

THEME SONG, DISNEY THEME PARKS

Since the 1980s, a spirit of deregulation and special exemptions has guided communication legislation. For example, in 1995, despite complaints from NBC, Rupert Murdoch’s Australian company News Corp. received a special dispensation from the FCC and Congress allowing the firm to continue owning and operating the Fox network and a number of local TV stations. The Murdoch decision ran counter to government decisions made after World War I. At that time, the government feared outside owners and thus limited foreign investment in U.S. broadcast operations to 20 percent. To make things easier, Murdoch became a U.S. citizen, and in 2004 News Corp. moved its headquarters to the United States, where the company was doing about 80 percent of its business.

FCC rules were further relaxed in late 2007, when the agency modified the newspaper-broadcast cross-ownership rule, allowing a company located in a Top 20 market to own one TV station and one newspaper as long as there were at least eight TV stations in the market. Previously, a company could not own a newspaper and a broadcast outlet—either a TV or radio station—in the same market (although if a media company had such cross-ownership prior to the early 1970s, the FCC usually granted waivers to let it stand). Murdoch had already been granted a permanent waiver from the FCC to own the New York Post and the New York TV station WNYW. So the FCC actually restructured the cross-ownership rule to accommodate News Corp. (In 2006, when News Corp. bought the New York–based Wall Street Journal, the FCC declared that the Journal was a national newspaper, not a local one that fell under the cross-ownership rule.) In 2011, the FCC voted to allow the same company to own a TV station and a newspaper in a Top 20 market. But in 2012, the Supreme Court let a lower court ruling stand that blocked the FCC’s deregulation of cross-ownership, so the rules still exist.

The deregulation movement favored by administrations from Reagan through Clinton to George W. Bush returned media economics to nineteenth-century principles, which suggested that markets can take care of themselves with little government intervention. In this context, one of the ironies in broadcast history is that more than eighty years ago commercial radio broadcasters demanded government regulation to control technical interference and amateur competition. By the mid-1990s, however, the original reasons given for regulation no longer applied. With new cable channels, DBS, and the Internet, broadcasting was no longer considered a scarce resource—once a major rationale for regulation as well as government funding of noncommercial and educational stations.