The Power of Visual Language

The shift from a print-dominated culture to an electronic-digital culture requires that we look carefully at differences among various approaches to journalism. For example, the visual language of TV news and the Internet often captures events more powerfully than words. Over the past fifty years, television news has dramatized America’s key events. Civil Rights activists, for instance, acknowledge that the movement benefited enormously from televised news that documented the plight of southern blacks in the 1960s. The news footage of southern police officers turning powerful water hoses on peaceful Civil Rights demonstrators or the news images of “white only” and “colored only” signs in hotels and restaurants created a context for understanding the disparity between black and white in the 1950s and 1960s.

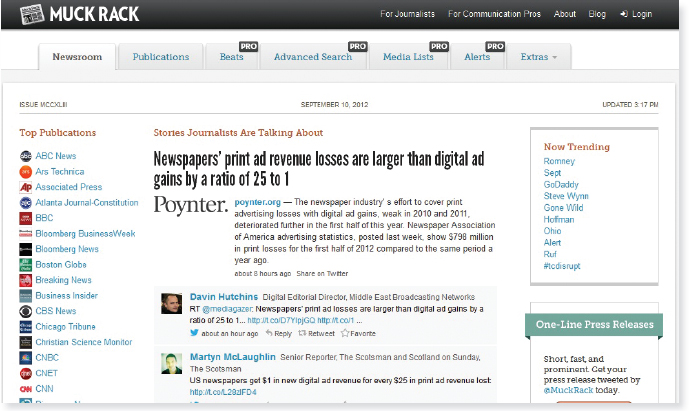

Today, more and more journalists use Twitter in addition to performing their regular reporting duties. Muck Rack collects journalists’ tweets in one place, making it easier than ever to access breaking news and real-time, one-line reporting.

VideoCentral  Mass Communication

Mass Communication

Fake News/Real News: A Fine Line

The editor of the Onion describes how the publication critiques “real” news media.

Discussion: How many of your news sources might be considered “fake” news versus traditional news, and how do you decide which sources to consult?

Other enduring TV images are also embedded in the collective memory of many Americans: the Kennedy and King assassinations in the 1960s; the turmoil of Watergate in the 1970s; the first space shuttle disaster and the Chinese student uprisings in the 1980s; the Oklahoma City federal building bombing in the 1990s; the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center in 2001; Hurricane Katrina in 2005; the historic 2008 election of President Obama; the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011; and in 2012 the brutal murders of twenty schoolchildren and six adults in Newtown, Connecticut. During these critical events, TV news has been a cultural reference point marking the strengths and weaknesses of our world. (See “Global Village: Al Jazeera Buys a U.S. Cable Channel” for more on global news access in the digital age.)

Today, the Internet, for good or bad, functions as a repository for news images and video, alerting us to stories that the mainstream media missed or to videos captured by amateurs. Remember the leaked video to Mother Jones magazine of candidate Mitt Romney at a fund-raiser during the 2012 election: “There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what … who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims. …” That footage, played over and over on YouTube and cable news, hurt Romney’s campaign. Then in summer 2013, CIA employee Edward Snowden chose a civil liberties advocate and columnist for the London-based Guardian to leak material on systematic surveillance of ordinary Americans by the National Security Agency. The video interview with the Guardian scored 1.5 million YouTube hits shortly after its release. As New York Times columnist David Carr noted at the time: “News no longer needs the permission of traditional gatekeepers to break through. Scoops can now come from all corners of the media map and find an audience just by virtue of what they reveal.”40