What Is News?

“The ‘information’ the modern media provide leaves people feeling use-less not because it’s so bleak but because it’s so trivial. It doesn’t inform at all; it only bombards with random data bits, faux trends, and surveys that reinforce preconceptions.”

SUSAN FALUDI, THE NATION, 1996

In a 1963 staff memo, NBC news president Reuven Frank outlined the narrative strategies integral to all news: “Every news story should … display the attributes of fiction, of drama. It should have structure and conflict, problem and denouement, rising and falling action, a beginning, a middle, and an end.”7 Despite Frank’s candid insights, many journalists today are uncomfortable thinking of themselves as storytellers. Instead, they tend to describe themselves mainly as information-gatherers.

News is defined here as the process of gathering information and making narrative reports—edited by individuals for news organizations—that offer selected frames of reference; within those frames, news helps the public make sense of important events, political issues, cultural trends, prominent people, and unusual happenings in everyday life.

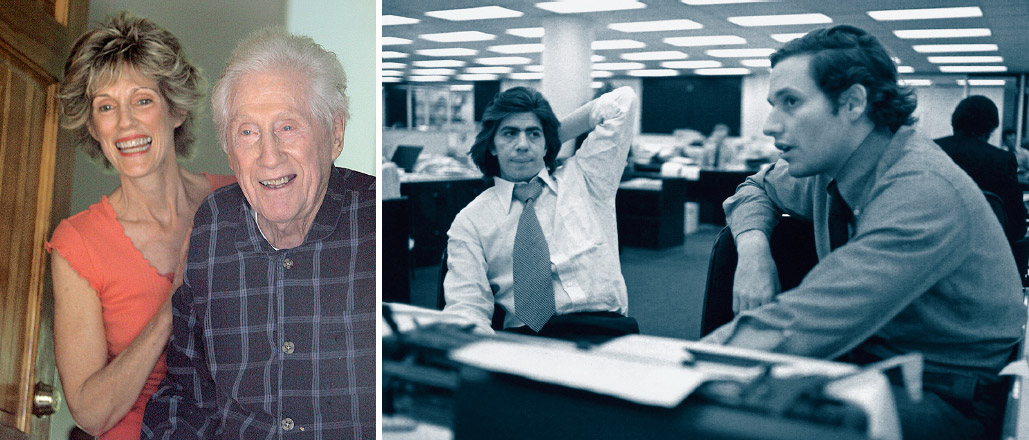

The major symbol of twentieth-century investigative journalism, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s (above right) coverage of the Watergate scandal for the Washington Post helped topple the Nixon White House. In All the President’s Men, the newsmen’s book about their investigation, a major character is Deep Throat, the key unidentified source for much of Woodward’s reporting. Deep Throat’s identity was protected by the two reporters for more than thirty years. Then in summer 2005 he revealed himself as Mark Felt (above), the former No. 2 official in the FBI during the Nixon administration. (Felt died in 2008.)

Characteristics of News

Over time, a set of conventional criteria for determining newsworthiness—information most worthy of transformation into news stories—has evolved. Journalists are taught to select and develop news stories relying on one or more of these criteria: timeliness, proximity, conflict, prominence, human interest, consequence, usefulness, novelty, and deviance.8

Most issues and events that journalists select as news are timely or new. Reporters, for example, cover speeches, meetings, crimes, and court cases that have just happened. In addition, most of these events have to occur close by, or in proximity to, readers and viewers. Although local TV news and papers offer some national and international news, readers and viewers expect to find the bulk of news devoted to their own towns and communities.

Most news stories are narratives and thus contain a healthy dose of conflict—a key ingredient in narrative writing. In developing news narratives, reporters are encouraged to seek contentious quotes from those with opposing views. For example, stories on presidential elections almost always feature the most dramatic opposing Republican and Democratic positions. And many stories in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, pitted the values of other cultures against those of Western culture—for example, Islam vs. Christianity or premodern traditional values vs. contemporary consumerism.

Reader and viewer surveys indicate that most people identify more closely with an individual than with an abstract issue. Therefore, the news media tend to report stories that feature prominent, powerful, or influential people. Because these individuals often play a role in shaping the rules and values of a community, journalists have traditionally been responsible for keeping a watchful eye on them and relying on them for quotes.

But reporters also look for the human-interest story: extraordinary incidents that happen to “ordinary” people. In fact, reporters often relate a story about a complicated issue (such as unemployment, war, tax rates, health care, or homelessness) by illustrating its impact on one “average” person, family, or town.

Two other criteria for newsworthiness are consequence and usefulness. Stories about isolated or bizarre crimes, even though they might be new, near, or notorious, often have little impact on our daily lives. To balance these kinds of stories, many editors and reporters believe that some news must also be of consequence to a majority of readers or viewers. For example, stories about issues or events that affect a family’s income or change a community’s laws have consequence. Likewise, many people look for stories with a practical use: hints on buying a used car or choosing a college, strategies for training a pet or removing a stain.

Finally, news is often about the novel and the deviant. When events happen that are outside the routine of daily life, such as a seven-year-old girl trying to pilot a plane across the country or an ex-celebrity involved in a drug deal, the news media are there. Reporters also cover events that appear to deviate from social norms, including murders, rapes, fatal car crashes, fires, political scandals, and gang activities. For example, as the war in Iraq escalated, any suicide bombing in the Middle East represented the kind of novel and deviant behavior that qualified as major news.