Contemporary Media Effects Theories

By the 1960s, the first departments of mass communication began graduating Ph.D.-level researchers schooled in experiment and survey research techniques, as well as content analysis. These researchers began documenting consistent patterns in mass communication and developing new theories. Five of the most influential contemporary theories that help explain media effects are social learning theory, agenda-setting, the cultivation effect, the spiral of silence, and the third-person effect.

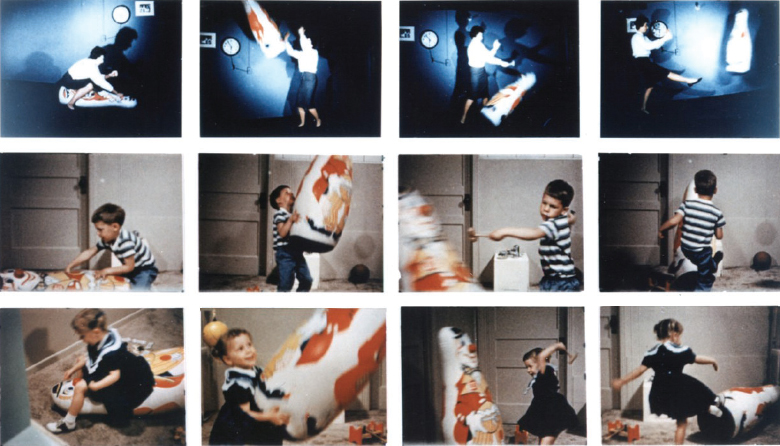

These photos document the “Bobo doll” experiments conducted by Albert Bandura and his colleagues at Stanford University in the early 1960s. Seventy-two children from the Stanford University Nursery School were divided into experimental and control groups. The “aggressive condition” experimental group subjects watched an adult in the room sit on, kick, and hit the Bobo doll with hands and a wooden mallet while saying such things as “Sock him in the nose,” “Throw him in the air,” and “Pow.” (In later versions of the experiment, children watched filmed versions of the adult with the Bobo doll.) Afterward, in a separate room filled with toys, the children in the “aggressive condition” group were more likely than the other children to imitate the adult model’s behavior toward the Bobo doll.

Social Learning Theory

Some of the most well-known studies that suggest a link between the mass media and behavior are the “Bobo doll” experiments, conducted on children by psychologist Albert Bandura and his colleagues at Stanford University in the 1960s. Bandura concluded that the experiments demonstrated a link between violent media programs, such as those on television, and aggressive behavior. Bandura developed social learning theory as a four-step process: attention (the subject must attend to the media and witness the aggressive behavior), retention (the subject must retain the memory for later retrieval), motor reproduction (the subject must be able to physically imitate the behavior), and motivation (there must be a social reward or reinforcement to encourage modeling of the behavior).

Supporters of social learning theory often cite real-life imitations of media aggression (see the beginning of the chapter) as evidence of social learning theory at work. Yet critics note that many studies conclude just the opposite—that there is no link between media content and aggression. For example, millions of people have watched episodes of CSI and The Sopranos without subsequently exhibiting aggressive behavior. As critics point out, social learning theory simply makes television, film, and other media scapegoats for larger social problems relating to violence. Others suggest that experiencing media depictions of aggression can actually help viewers let off steam peacefully through a catharsis effect.

Agenda-Setting

The West African nation of Mali has been in the midst of a political crisis since its northern region was seized by rebel forces in 2012. One of the most devastating outcomes of the country’s political strife is the recruitment of child soldiers, as desperate, poor families often give up their children to rebels in exchange for food and money. Despite the devastation in Mali, many feel the international response to Mali’s crisis has been woefully inadequate and the mass media’s coverage equally insufficient.

A key phenomenon posited by contemporary media effects researchers is agenda-setting: the idea that when the mass media focus their attention on particular events or issues, they determine—that is, set the agenda for—the major topics of discussion for individuals and society. Essentially, agenda-setting researchers have argued that the mass media do not so much tell us what to think as what to think about. Traceable to Walter Lippmann’s notion in the early 1920s that the media “create pictures in our heads,” the first investigations into agenda-setting began in the 1970s.20

Over the years, agenda-setting research has demonstrated that the more stories the news media do on a particular subject, the more importance audiences attach to that subject. For instance, when the media seriously began to cover ecology issues after the first Earth Day in 1970, a much higher percentage of the population began listing the environment as a primary social concern in surveys. When Jaws became a blockbuster in 1975, the news media started featuring more shark attack stories; even landlocked people in the Midwest began ranking sharks as a major problem, despite the rarity of such incidents worldwide. More recently, extensive news coverage about the documentary An Inconvenient Truth and its companion best-selling book in 2006 sparked the highest-ever public concern about global warming, according to national surveys. But in the following years the public’s sense of urgency faltered somewhat as stories about the economy and other topics dominated the news agenda.

The Cultivation Effect

Another mass media phenomenon—the cultivation effect—suggests that heavy viewing of television leads individuals to perceive the world in ways that are consistent with television portrayals. This area of media effects research has pushed researchers past a focus on how the media affects individual behavior and toward a focus on larger ideas about the impact on perception.

The major research in this area grew from the attempts of George Gerbner and his colleagues to make generalizations about the impact of televised violence. The cultivation effect suggests that the more time individuals spend viewing television and absorbing its viewpoints, the more likely their views of social reality will be “cultivated” by the images and portrayals they see on television.21 For example, Gerbner’s studies concluded that although fewer than 1 percent of Americans are victims of violent crime in any single year, people who watch a lot of television tend to overestimate this percentage. Such exaggerated perceptions, Gerbner and his colleagues argued, are part of a “mean world” syndrome, in which viewers with heavy, long-term exposure to television violence are more likely to believe that the external world is a mean and dangerous place.

According to the cultivation effect, media messages interact in complicated ways with personal, social, political, and cultural factors; they are one of a number of important factors in determining individual behavior and defining social values. Some critics have charged that cultivation research has provided limited evidence to support its findings. In addition, some have argued that the cultivation effects recorded by Gerbner’s studies have been so minimal as to be benign and that, when compared side-by-side, the perceptions of heavy television viewers and nonviewers in terms of the “mean world” syndrome are virtually identical.

The Spiral of Silence

“Many studies currently published in mainstream communication journals seem filled with sophisticated treatments of trivial data, which, while showing effects … make slight contributions to what we really know about human mass-mediated communication.”

WILLARD ROWLAND AND BRUCE WATKINS, INTERPRETING TELEVISION, 1984

Developed by German communication theorist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann in the 1970s and 1980s, the spiral of silence theory links the mass media, social psychology, and the formation of public opinion. The theory proposes that those who believe that their views on controversial issues are in the minority will keep their views to themselves—that is, become silent—for fear of social isolation, which diminishes or even silences alternative perspectives. The theory is based on social psychology studies, such as the classic conformity research studies of Solomon Asch in 1951. In Asch’s study on the effects of group pressure, he demonstrated that a test subject is more likely to give clearly wrong answers to questions about line lengths if all other people in the room unanimously state an incorrect answer. Noelle-Neumann argued that mass media, particularly television, can exacerbate this effect by communicating real or presumed majority opinions widely and quickly.

According to the theory, the mass media can help create a false, overrated majority; that is, a true majority of people holding a certain position can grow silent when they sense an opposing majority in the media. One criticism of the theory is that some people may not fall into a spiral of silence because they don’t monitor the media, or they mistakenly perceive that more people hold their position than really do. Noelle-Neumann acknowledges that in many cases, “hard-core” nonconformists exist and remain vocal even in the face of social isolation and can ultimately prevail in changing public opinion.22

The Third-Person Effect

Identified in a 1983 study by W. Phillips Davison, the third-person effect theory suggests that people believe others are more affected by media messages than they are themselves.23 In other words, it proposes the idea that “we” can escape the worst effects of media while still worrying about people who are younger, less educated, more impressionable, or otherwise less capable of guarding against media influence.

Under this theory, we might fear that other people will, for example, take tabloid newspapers seriously, imitate violent movies, or get addicted to the Internet, while dismissing the idea that any of those things could happen to us. It has been argued that the third-person effect is instrumental in censorship, as it would allow censors to assume immunity to the negative effects of any supposedly dangerous media they must examine.