15.1 Early Media Research Methods

“The pictures inside the heads of these human beings, the pictures of themselves, of others, of their needs, purposes, and relationships, are their public opinions.”

WALTER LIPPMANN, PUBLIC OPINION, 1922

In the early days of the United States, philosophical and historical writings tried to explain the nature of news and print media. For instance, the French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America, noted differences between French and American newspapers in the early 1830s:

In France the space allotted to commercial advertisements is very limited, and … the essential part of the journal is the discussion of the politics of the day. In America three quarters of the enormous sheet are filled with advertisements and the remainder is frequently occupied by political intelligence or trivial anecdotes; it is only from time to time that one finds a corner devoted to the passionate discussions like those which the journalists of France every day give to their readers.1

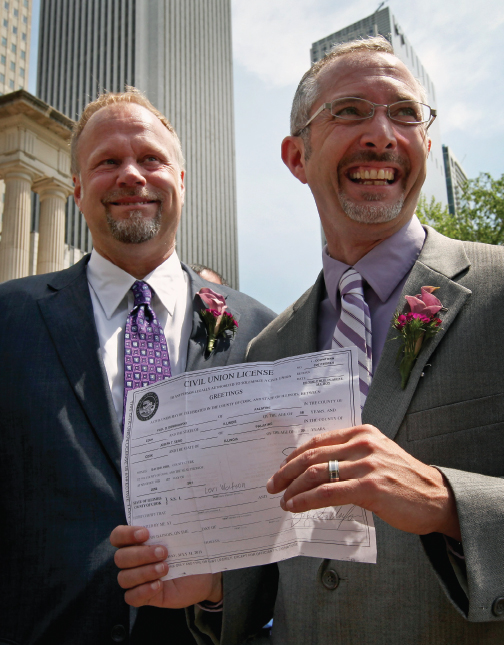

Recent public opinion polls suggest that the American public’s attitude toward same-sex marriage is changing. Just weeks before the Supreme Court ruled to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), a 2013 Washington Post-ABC poll found that 63 percent of Americans were already in favor of extending federal benefits to legally married same-sex couples.

During most of the nineteenth century, media analysis was based on moral and political arguments, as noted in the de Tocqueville quote.2

More scientific approaches to mass media research did not begin to develop until the late 1920s and 1930s. In 1920, Walter Lippmann’s Liberty and the News called on journalists to operate more like scientific researchers in gathering and analyzing factual material. Lippmann’s next book, Public Opinion (1922), was the first to apply the principles of psychology to journalism. Considered by many academics to be “the founding book in American media studies,”3 it led to an expanded understanding of the effects of the media, emphasizing data collection and numerical measurement. According to media historian Daniel Czitrom, by the 1930s “an aggressively empirical spirit, stressing new and increasingly sophisticated research techniques, characterized the study of modern communication in America.”4 Czitrom traces four trends between 1930 and 1960 that contributed to the rise of modern media research: propaganda analysis, public opinion research, social psychology studies, and marketing research.