Media Research and Democracy

“My idea of a good time is using jargon and citing authorities.”

MATT GROENING, SCHOOL IS HELL, 1987

One charge frequently leveled at academic studies is that they fail to address the everyday problems of life; they often seem to have little practical application. The growth of mass media departments in colleges and universities has led to an increase in specialized jargon, which tends to alienate and exclude nonacademics. Although media research has built a growing knowledge base and dramatically advanced what we know about the effect of mass media on individuals and societies, the academic world has paid a price. That is, the larger public has often been excluded from access to the research process even though cultural research tends to identify with marginalized groups. The scholarship is self-defeating if its complexity removes it from the daily experience of the groups it addresses. Researchers themselves have even found it difficult to speak to one another across disciplines because of discipline-specific language used to analyze and report findings. For example, understanding the elaborate statistical analyses used to document media effects requires special training.

“In quantum gravity, as we shall see, the space-time manifold ceases to exist as an objective reality; geometry becomes relational and contextual; and the foundational conceptual categories of prior science—among them, existence itself—become problematized and relativized. This conceptual revolution, I will argue, has profound implications for the content of a future postmodern and liberatory science.”

FROM ALAN SOKAL’S PUBLISHED JARGON-RIDDLED HOAX, 1996

In some cultural research, the language used is often incomprehensible to students and to other audiences who use the mass media. A famous hoax in 1996 pointed out just how inaccessible some academic jargon can be. Alan Sokal, a New York University physics professor, submitted an impenetrable article, “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity,” to a special issue of the academic journal Social Text devoted to science and postmodernism. As he had expected, the article—a hoax designed to point out how dense academic jargon can sometimes mask sloppy thinking—was published. According to the journal’s editor, about six reviewers had read the article but didn’t suspect that it was phony. A public debate ensued after Sokal revealed his hoax. Sokal said he worries that jargon and intellectual fads cause academics to lose contact with the real world and “undermine the prospect for progressive social critique.”35

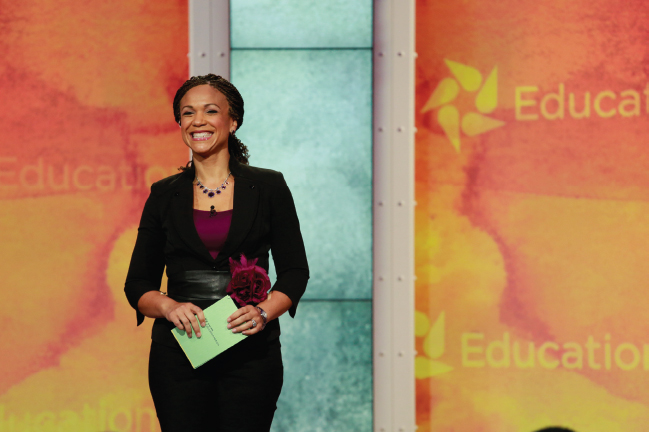

In addition, increasing specialization in the 1970s began isolating many researchers from life outside of the university. Academics were locked away in their “ivory towers,” concerned with seemingly obscure matters to which the general public couldn’t relate. Academics across many fields, however, began responding to this isolation and became increasingly active in political and cultural life in the 1980s and 1990s. For example, literary scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. began writing essays for Time and the New Yorker magazines. Linguist Noam Chomsky has written for decades about excessive government and media power; he was also the subject of an award-winning documentary, Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and The Media. Essayist and cultural critic Barbara Ehrenreich has written often about labor and economic issues in magazines such as Time and The Nation. In her 2008 book This Land Is Their Land: Reports from a Divided Nation, she investigates incidents of poverty among recent college graduates, undocumented workers, and Iraq war military families, documenting the wide divide between rich and poor. Georgetown University sociology professor Michael Eric Dyson, author of the book April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Death and How It Changed America, made frequent appearances on network and cable news channels during the 2008 presidential campaign to speak on the issues of race and the meaning of Barack Obama’s historic candidacy. Melissa Harris-Perry, a political science professor at Tulane, writes about race, class, and politics for The Nation, and also hosts a news and opinion show for MSNBC.

Melissa Harris-Perry writes about race, class, and politics for The Nation, and also hosts a weekend news and opinion show for MSNBC. Her most recent book is Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America.

In recent years, public intellectuals have also encouraged discussion about media production in a digital world. Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig has been a leading advocate of efforts to rewrite the nation’s copyright laws to enable noncommercial “amateur culture” to flourish on the Internet. American University’s Pat Aufderheide, longtime media critic for the alternative magazine In These Times, worked with independent filmmakers to develop the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use, which calls for documentary filmmakers to have reasonable access to copyrighted material for their work.

Like public journalists, public intellectuals based on campuses help carry on the conversations of society and culture, actively circulating the most important new ideas of the day and serving as models for how to participate in public life.